In seaside village, turtles VIP visitors

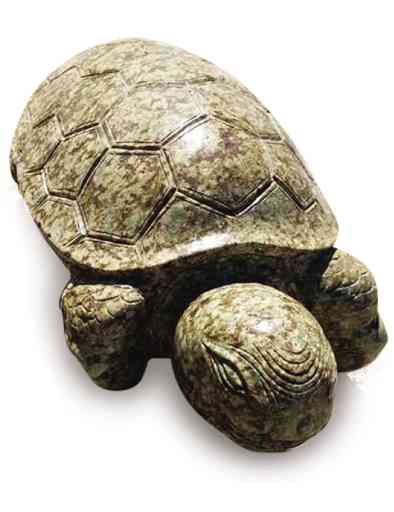

A STATUE of a sea turtle was sent as a gift by a Korean sculptor to the village of Dalumpinas Oeste in La Union’s San Fernando City, which has served as birthing home for the sea creatures for years now. CONTRIBUTED PHOTO

SAN FERNANDO CITY—It was a race to the sea for survival. On Jan. 26, just before sunrise, village officials and residents of Barangay Dalumpinas Oeste here, sent 125 sea turtle hatchlings into the water.

It was the first test of endurance for the two-inch long, hours-old turtles. They may survive the first race, but most may not survive in the wild marine environment.

These baby sea turtles were the fourth set released by villagers since December last year, as part of Dalumpinas Oeste’s pawikan conservation program started in 2010, according to village chair Alvin Alviar.

Alviar said while the village beach is less popular than that of San Juan, a neighboring town which attracts surfers, Dalumpinas Oeste is frequented by other visitors—turtles.

“Our beach is unknown,” said Alviar. “But our beach’s serenity and unspoiled state attract a different kind of visitor each year—sea turtles that come to nest in the sand,” he said.

Article continues after this advertisement“We want our beach to be known for something significant and since sea turtles come here every year to lay eggs, we decided to start a pawikan conservation program,” he said, adding that the program was started by former village head Marvin Munar.

Article continues after this advertisementLessons learned

At first, the village found ways to protect the turtles nests, learning lessons from the Coastal Underwater Resource Management Actions (Curma), a group in San Juan which, for years, has been caring for pawikan nesting on its beaches.

Jane Ortega, former mayor, said sea turtles look for new nests because the beach in San Juan had become crowded with resorts and restaurants.

Barangay Dalumpinas Oeste is the last village north of San Fernando before the surfing area of San Juan.

Village residents had been hosting mother sea turtles since 2010 and in 2015, they asked the city government for help in the conservation project.

Alviar said seven sea Olive Ridley species came to nest in Dalumpinas beach in 2012 while eight came in 2013 and 2014. In 2015, four turtles came and their eggs were hatched on Dec. 1 (85 hatchlings), Dec. 4 (97 hatchlings) and Dec. 24 (74 hatchlings). The last batch of eggs hatched on Jan. 26. The nesting season starts in October when the mother turtles come.

“We know they have arrived because of their tracks on the beach. The mothers leave after depositing the eggs two feet under the sand,” Alviar said.

Clever turtles

“But they are clever,” he said. “They make several tracks to mislead us,” said Alviar.

Conservationists, however, locate the eggs by inserting sticks into the sand near the turtle tracks. “If the beach is soft, the eggs are there,” he said.

If the eggs are unprotected, only 1 percent hatch “because animals could find and eat them.” The eggs incubate for 45-75 days.

When the time comes for the eggs to hatch, conservation workers stay up the entire night to wait for the hatchlings to emerge from the sand.

“It is always an exciting moment. We are like expectant mothers and fathers waiting for our kids to come into the world,” Alviar said.

After all the eggs are hatched, the hatchlings surface from the sand and get fidgety, as if longing for the comfort of the sea. “The hatchlings must be released to the sea before the sun rises or they will get disoriented and won’t find their way to the water, or even get blinded by the sun,” Alviar said.