Mexico finds main skull rack at Aztec temple complex

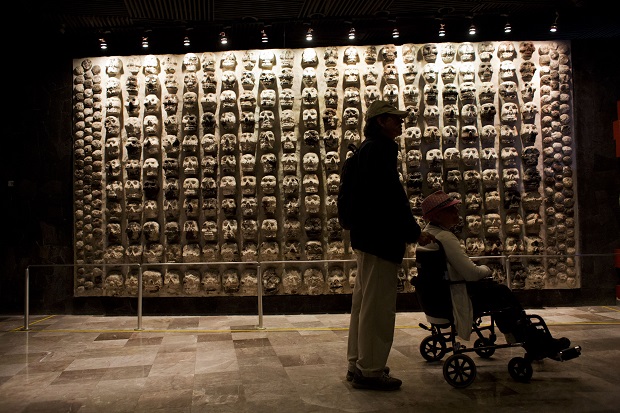

A man pushes a woman in a wheelchair past a wall of ancient stone skulls, excavated at Templo Mayor, that represent sacrificial victims, at the entrance to the Templo Mayor museum in central Mexico City, Friday, Aug. 7, 2015. In the pantheon of Mexico’s pre-Hispanic gods, most Aztec dieties are depicted as brutal, blood-thirsty gods, only appeased by human sacrifices. But the Templo Mayor museum has put on display for the first time an offering dedicated to Xochipilli, the Aztec god of singing, dancing, and the morning sun. The offering was found in 1978 during excavations of the Red Temple, a small altar adjacent to Templo Mayor. AP

MEXICO CITY — Archaeologists have found the main trophy rack of sacrificed human skulls at Mexico City’s Templo Mayor Aztec ruin site, scientists said Thursday.

Racks known as “tzompantli” were where the Aztecs displayed the severed heads of sacrifice victims on wooden poles pushed through the sides of the skull. The poles were suspended horizontally on vertical posts.

Eduardo Matos, an archaeologist at the National Institute of Anthropology and History, suggested the skull rack in Mexico City “was a show of might” by the Aztecs. Friends and even enemies were invited into the city, precisely to be cowed by the grisly display of heads in various stages of decomposition.

Paintings and written descriptions from the early colonial period showed descriptions of such racks. But institute archaeologists said the newest discovery was different.

Part of the platform where the heads were displayed was made of rows of skulls mortared together roughly in a circle, around a seemingly empty space in the middle. All the skulls were arranged to look inward toward the center of the circle, but experts don’t know what was at the center.

Article continues after this advertisementArchaeologist Raul Barrera said that “there are 35 skulls that we can see, but there are many more” in underlying layers. “As we continue to dig the number is going to rise a lot.”

Article continues after this advertisementBarrera noted that one Spanish writer soon after the conquest described mortared-together skulls, but none had been found before.

University of Florida archaeologist Susan Gillespie, who was not involved in the project, wrote that “I do not personally know of other instances of literal skulls becoming architectural material to be mortared together to make a structure.”

The find was made between February and June on the western side of what was once the Templo Mayor complex.

The platform was partly excavated under the floor of a three-story colonial era house. Because the house was historically valuable, archaeologists often worked in narrow excavation wells six feet (two meters) under the floor level suspended on their stomachs on a wooden platform.

Periodic excavations carried out since 1914 suggested a ceremonial site was located near the site. Barrera said the location fit very well with the first Spanish descriptions of the temple complex.

Gillespie said archaeologists have found other tzompantli, which she said might be better translated as “head rack” instead of “skull rack” because the heads were put up for display while still fresh.

But experts had long been searching for the main one.

“They’ve been looking for the big one for some time, and this one does seem much bigger than the already excavated one,” Gillespie wrote. “This find both confirms long-held suspicions about the sacrificial landscape of the ceremonial precinct, that there must have been a much bigger tzompantli to curate the many heads of sacrificial victims” as a kind of public record or accounting of sacrifices.