Lim, Estrada approved Torre de Manila permits

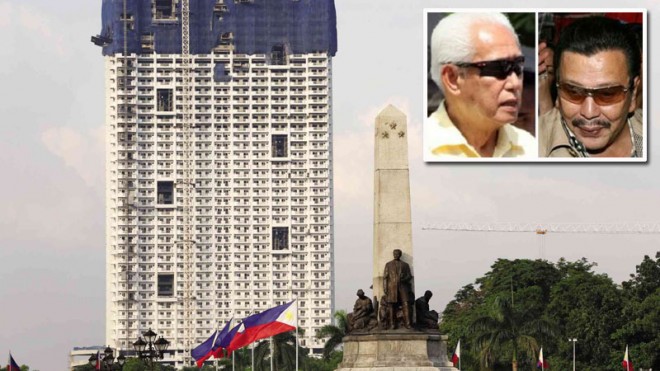

Rizal Monument with Torre Manila shown in the background. Inset, former Manila Mayor Alfredo Lim (left) and current Mayor Joseph Estrada. INQUIRER FILE PHOTOS

From the former mayor to the current city administration, the local government of Manila committed lapses that led to the rise of Torre de Manila that many say mars the view of the Rizal Monument.

This surfaced on Tuesday during the fourth round of oral arguments on the case seeking the building’s demolition, when Associate Justice Francis Jardeleza grilled city officials for three hours, stopping only when Chief Justice Maria Lourdes Sereno decided to adjourn the session at 5 p.m. because of bad weather.

Despite clear requirements under a local ordinance, former Manila Mayor Alfredo Lim may well have violated the rule of law when he ordered his officials to process DM Consunji Inc.’s (DMCI) zoning permit application for a 49-story Torre de Manila despite height limits on its site on Taft Avenue.

Jardeleza elicited this in the course of questioning Manila City legal officer Jose Alberto Flaminiano, who conceded that former city officials may be held both administratively and criminally liable for issuing a zoning permit for Torre de Manila.

The city government is among the parties impleaded in the Knights of Rizal’s petition seeking the demolition of Torre de Manila for violating the sight line of the Rizal Monument, a national landmark.

Article continues after this advertisementCiting provisions of Manila’s zoning law, Ordinance No. 8119, Jardeleza established that Torre de Manila’s site was classified as a university cluster zone. The building stands on a site where only schools and government buildings of up to seven stories are allowed under the local regulation.

Article continues after this advertisementNo application

Jardeleza found that the Lim administration granted DMCI a zoning permit on June 19, 2012, for Torre de Manila even without the developer’s application for a variance (exemption) from zoning restrictions, as required under the ordinance.

“When permits were granted, there were no applications for variance?” Jardeleza asked Flaminiano. The lawyer responded, “None, your honor.”

Jardeleza noted that the ordinance, under Sections 60, 61 and 62, required any developer seeking an exemption from zoning limits to formally file for such variance.

“Under the rule of law, there is no exception to that,” Jardeleza said.

Criminally liable

“And so if this happens under your administration now, where a city planning officer and building official gives zoning permit under the same facts, what do you call that?” he asked Flaminiano.

“I would say he acted beyond the scope of his authority,” Flaminiano said.

“What type of infraction would that be?” Jardeleza said.

“I would say an administrative liability,” Flaminiano answered.

“Is that slight?” the justice asked.

“I would not describe it as slight. [It is] perhaps a serious or grave misconduct,” the city legal officer said.

The lawyer also agreed that such official may be held criminally liable “if there is evidence, your honor.”

Jardeleza also found that Manila’s former city planning and development officer Resty Rebong had said that Manila’s “executive branch” suspended the ordinance’s provision on height limitations “for it opted to follow the National Building Code.”

This set the magistrate off to a further line of questioning, citing the zoning ordinance’s “four layers of protection” covering Torre de Manila’s site.

These layers are the site’s classification as a university cluster, the concept of historical-cultural preservation, Section 23 of the ordinance which regulates the use of areas classified as a “Planned Unit Development/Overlay Zone” and Section 47, which requires developers to first execute a “heritage impact statement” in applying for a zoning permit.

Jardeleza asked Flaminiano if city officials were “allowed to bend all four layers of protection” and allow the rise of a building of a forbidden height on a restricted site “ex-cathedra.”

“As a matter of the rule of law, can the mayor of the City of Manila, whether the then mayor or the present mayor, unilaterally suspend the four layers of protection or requirements that I walked you through?” Jardeleza asked Flaminiano.

“I don’t believe so, your honor,” the lawyer replied.

“Because you can read Ordinance No. 8119 forward and backward, backward and forward, you are required to go through a process. If you were a city legal officer then, would you have issued such legal opinion (that zoning restrictions can be suspended)?” Jardeleza continued.

“No, your honor,” Flaminiano said.

“Of course you will not because you believe in the rule of law,” the justice said.

Flaminiano also recalled a conversation with Rebong sometime in 2012, when he quoted former Mayor Lim as saying that City Hall should readily process DMCI’s papers during the time the developer was still applying for permits.

When Rebong apparently told Lim that his office had yet to receive the documents, “Lim allegedly said ‘o basta may natanggap kayo, i-process niyo yan (Just say you received something and you process it),” Flaminiano told the court.

“According to him (Rebong), the mayor said that just so developers wouldn’t have a hard time, documents should not go through the City Council,” said the city legal officer.

Flaminiano also cited Rebong’s narration that the Manila Zoning Board of Adjustments and Appeals was activated only for one project during Lim’s time. Jardeleza ordered the legal officer to confirm this with the city’s records.

The City Council investigated the zoning permit granted to Torre de Manila on July 24, 2012, but Lim allowed the construction nonetheless, Flaminiano said in his opening statement on Tuesday.

Vista protection vetoed

When the city council passed Ordinance No. 8310 in 2013 to protect the vista of Manila’s historical sites, Lim vetoed it.

Upon the change of administration, DMCI sought clarification “and expressed willingness to conform with necessary steps to comply with the appeals process under [the] Manila zoning ordinance,” Flamiano said.

Manila Mayor Joseph Estrada discussed this over lunch with the city planning and development officer Danilo Lacuna Jr. sometime in December 2013, the latter told Jardeleza upon questioning on Tuesday.

“I was the one who apprised him (Estrada) that DMCI was engaging our office as regards the appeal,” Lacuna said.

Estrada: Help developer

“The mayor told me to help the developer, to make sure they go through the process,” he told the court.

Jardeleza inquired how Lacuna took this to mean. “It means he did not want to discourage developers from building that high. His words were [that] ‘he encourages developers to invest in the city,’” the architect replied.

Lacuna also said it was he who told DMCI to formally, instead of just verbally, apply for a variance.

Lacuna admitted to Jardeleza that he had failed to advise DMCI to particularly cite Section 60 of the zoning ordinance in seeking a variance. “It was a lapse on my part. I forgot to tell them that they need to write an application citing a specific section,” he said.

In January 2014, the Estrada administration affirmed “all previously permits issued” for the Torre de Manila project, paving the way for its continued construction.

The oral arguments will resume on Aug. 25. Tarra Quismundo

RELATED STORIES

Tale of 2 mayors on Torre de Manila issue