‘Who really owns water?’

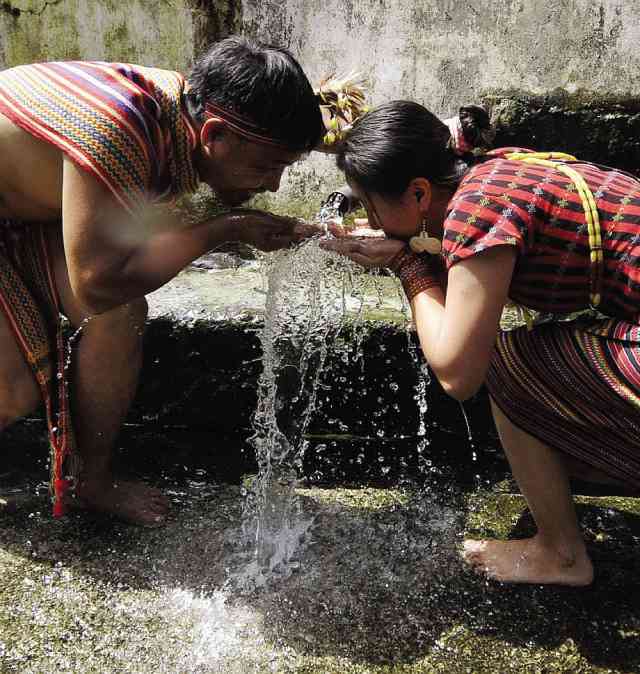

IN BALBALAN town in Kalinga, residents enjoy a continuous supply of water from an upland spring. EV ESPIRITU

DAYS BEFORE his final State of the Nation Address (Sona), President Aquino revealed something about water governance that should have given Filipinos pause.

“The water sector was so complicated when I assumed office. I discovered that no less than 30 agencies take part in regulating the water sector,” Mr. Aquino recounted saying this when he visited Angat Dam in Bulacan on July 22.

“What made that situation worse was these institutions acted independently, their respective plans were made impulsively, using insufficient data, while wading through interagency politics. If we compare the water sector to a band, it is as if each member plays a different instrument, producing discordant sounds instead of music,” he said.

“The result: service was bad and we still had insufficient water supply,” he added.

Mr. Aquino revealed this against the backdrop of Angat’s diminished reservoir supply, a consequence of this year’s prolonged dry spell that recently forced authorities to ration Metro Manila’s water supply.

Article continues after this advertisementHe said his solution at the beginning of his administration was to put “the band” under the baton of Public Works Secretary Rogelio Singson, who leads the interagency committee on the water sector.

Article continues after this advertisement

Deeper reason

But researchers believed there was a deeper reason for “the nestedness and interlocking set of decisions” made to produce and distribute water, and even the way people consume it.

Before the government reforms water regulations, they said, it should first acknowledge that the rules are dictated by how each Filipino answers this question: “Who really owns water?”

The University of the Philippines found that out when it examined how Filipinos use water, in light of the impact of climate change on water supply.

UP president Alfredo Pascual pooled scholars from campuses in Baguio, Los Baños and Visayas through the system’s Emerging Interdisciplinary Research Program (EIDR), hoping to understand the roots of the water sector’s sad state of affairs, said Raymundo Rovillos, UP Baguio chancellor.

The UP EIDR study, “Toward Good Water Governance for Development: A Multi-Case Analysis,” surveyed 299 water district administrators, irrigators’ associations, local governments and community-based organizations in 10 provinces about their thoughts on water laws, policies and administration—the elements of water governance.

The weaknesses of the water governance mechanisms in the country have become more apparent as provinces deal with water rationing, transboundary issues and conflicts between communities living upstream and downstream of a crucial river system, according to the study’s initial findings presented at the International Conference on Building Resilience and Developing Sustainability held in UP Baguio early this year.

“While there is a unanimous view that everyone has a right to water, equity in access and participation in decision-making is far from perfect,” said professors Agnes Rola (UPLB), Corazon Abansi (UP Baguio), Rosalie Arcala Hall (UP Visayas) and Joy Lizada (UP Visayas) who drew up the EIDR study.

“Decisions about policies, laws, institutional structure, incentives and capacity development are made by a multilayer of decision-makers: national, regional, local and even ethnic authorities,” the study said.

Public good

The UP team said for many Filipinos, “water is partially a public good” as well as “an integral part of the ecosystem, a natural resource, and a social and economic good.”

This perception may run counter to established jurisprudence.

A draft of a second UP study, “Towards Establishing Water Security and Urban Resilience in the City of Baguio: A Working Paper,” said:

“By constitutional and statutory mandate all waters, within the territorial borders of the Philippines, regardless of source, are understood to be owned by the Philippine state.”

“The only waters that the state allows individuals to have ‘exclusive control’ and right of disposal are those that are already ‘capture[d] and collect[ed]… by means of cisterns, tanks or pools.’ Notice, however, that the law used the word ‘control’ and not ownership. This goes to show how the state jealously guards its assumed title over the waters,” said UP Baguio professor Alejandro Ciencia, the study’s lead

researcher.

‘No one size fits all’

“The basis for this strong legal pronouncement of state ownership over the waters is attributed to the long standing regalian doctrine; a principle which establishes the foundation for state’s title over all resources within the confines of its territory,” he said.

A “scarcity of water,” however, is also cited by Presidential Decree No. 1067 (Water Code of the Philippines) as reason “for protecting this resource against private ownership,” Ciencia said.

“It is imperative that the Philippine policymakers recognize that even in the country, no one size fits all,” the EIDR study said.

Balancing act

It said water managers, whether something as structured as water districts or as informal as communal water distributors, “are faced with the issue on how to achieve the right balance between managing water as an economic [commodity] and a social good.”

But any balancing act is tricky.

The study said majority (70 percent) of water managers set a priority list of customers, equity being their “topmost consideration for such allocation.”

“An overwhelming number ranked domestic use as first (78.6 percent) [of the priority consumers], followed closely by irrigation (54.8 percent). Industrial use (61.6 percent) and environment (47.8 percent) were rated as second priority. Power generation and navigation received the lowest rankings,” it said.

To keep faucets running, however, water managers require some form of return-on-investments. Water managers, such as local water districts and irrigation associations, “recognize that water has become a scarce resource,” the study said, so “pricing instruments are used as fundamental tools to ensure the sustainability of water systems and the efficiency of water allocation.”

The UP team said low irrigation water charges encourage farmers to use water inefficiently. “Farmers only cut their water consumption if the water price is so high that it considerably affects their profits,” it said.