Japan ends nuclear shutdown four years after Fukushima

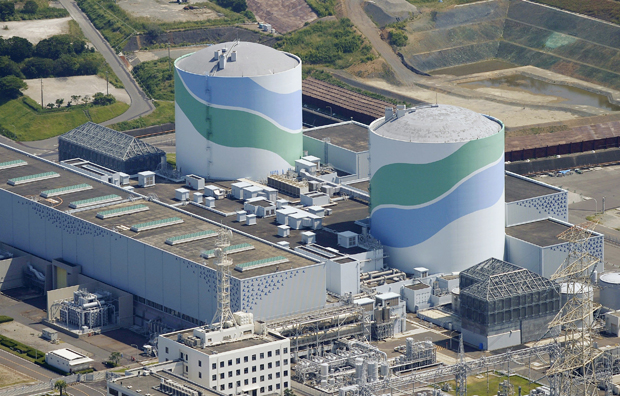

This aerial photo shows reactors of No. 1, right, and No. 2, left, at the Sendai Nuclear Power Station in Satsumasendai, Kagoshima prefecture, southern Japan, Tuesday, August 11, 2015. Kyushu Electric Power Co. said it had restarted the No. 1 reactor at its Sendai nuclear plant as planned. The restart marks Japan’s return to nuclear energy four-and-half-years after the 2011 meltdowns at the Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power plant in northeastern Japan following an earthquake and tsunami. AP

TOKYO, Japan – Japan switched on a nuclear reactor Tuesday, ending a two-year shutdown in the energy-hungry country that was sparked by public fears following the 2011 Fukushima crisis, the worst atomic disaster in a generation.

Utility Kyushu Electric Power, which operates the reactor at Sendai about 1,000 kilometers (620 miles) southwest of Tokyo, said it was turned on at 10:30 am (0130 GMT).

The 31-year-old reactor – operating under tougher post-Fukushima safety rules – was expected to reach full capacity around 11:00 pm Tuesday and would start generating power by Friday.

Commercial operations are to begin early next month, the spokesman said.

The restart comes more than four years after a quake-generated tsunami triggered meltdowns at the Fukushima plant, prompting the shutdown of Japan’s stable of reactors and setting off a pitched battle over the future use of atomic power.

Article continues after this advertisementAnti-nuclear sentiment still runs high in Japan and there were reports Tuesday of protesters scuffling with police in front of the Sendai plant, which is on the southernmost main island of Kyushu. Local media said about 200 protesters gathered in front of the plant.

Article continues after this advertisementThe resource-poor nation, which once relied on nuclear power for a quarter of its electricity, restarted two reactors temporarily to feed its needs. But they both went offline by September 2013, making Japan completely nuclear-free for about two years.

The country has ushered in stricter safety regulations to avoid a repeat of Fukushima, including more backup prevention measures and higher tsunami-blocking walls in areas most susceptible to them.

The measures are key to Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s bid to get some of about four dozen reactors back up and running.

Power companies that own them are also keen for more restarts, fed up with having to make up lost generating capacity with pricey fossil fuels.

Stricter rules

Japan’s post-Fukushima energy bill skyrocketed as it scrambled to fill the gap left by taking reactors offline, pushing the country into successive trade deficits.

Those expenses were exacerbated by a sharp weakening of the yen, which pushed up costs for energy imports paid for in other currencies, particularly the US dollar.

A subsequent drop in energy prices had alleviated some of the strain.

Several other reactors have received a safety green light from officials, but battle lines have been drawn with many local communities strongly against restarting reactors in their region.

Safety officials have stressed that any switched-on reactor would operate under much tighter regulations than those that existed before Fukushima, the worst atomic disaster since Chernobyl in 1986.

“A disaster like that at Tokyo Electric Power’s Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant will not occur,” under the new rules, Nuclear Regulation Authority chairman Shunichi Tanaka said in an interview with the Nikkei newspaper published at the weekend.

“The new regulations are incomparably (stricter) than those under the old system.”

Tanaka conceded there was “no such thing as absolute safety”, but said any future crisis would “be contained before it reached a scale anywhere near what happened in Fukushima”.

But Japan’s people are sceptical and the country remains deeply scarred by Fukushima, which forced tens of thousands of people from their homes — many of whom will likely never return.

“Rather than a nuclear renaissance, much of Japan’s ageing nuclear reactor fleet will never restart,” said Mamoru Sekiguchi, an energy campaigner at Greenpeace Japan.

“Prime Minister Abe and the nuclear regulator are risking Japan’s safety for an energy source that will likely fail to provide the electricity the nation will need in the years ahead.”

Sekiguchi added that Japan’s use of nuclear power would likely fall far short of the government’s 22 percent target by 2030.