Baroque losing to Bieber: Bamboo Organ fest bowing out?

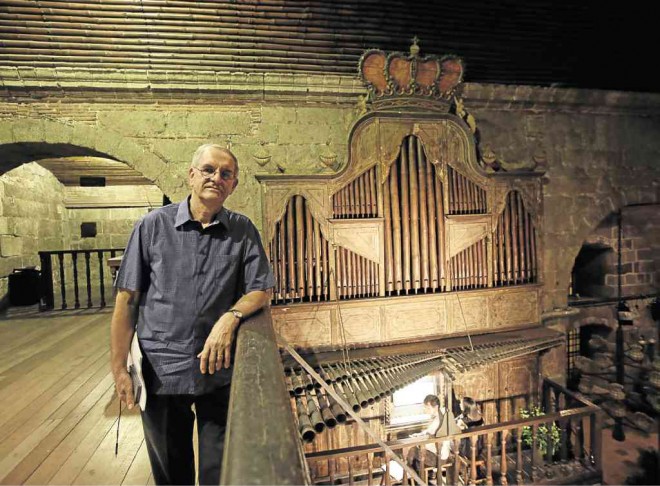

FADING NOTES Leo Renier, executive director of the 40th International Bamboo Organ Festival, stands next to the world-famous instrument inside St. Joseph church, Las Piñas City. AP

The nearly 200-year-old bamboo pipe organ of Las Piñas City, said to be the oldest and most complete in the world, has survived time, storms and wars. But an annual concert festival that has showcased its unique, lilting music in a Roman Catholic church for four decades may be playing out for the last time due to waning funds and interest in a country where many have been enthralled by modern Western music.

The clear, flute-like sounds produced by the organ’s 902 bamboo and 129 metal pipes have captivated music lovers for decades. By pulling different knobs, an organist can make the instrument produce distinct sounds that one player said was like calling on different members of an orchestra, one after another.

Organizers of the International Bamboo Organ Festival hope history, pride and a rediscovery of Baroque music from the country’s musical past will prompt Filipinos not to abandon a yearly tradition that has attracted renowned musicians and curious visitors from as far as Europe and the United States.

Belgian Leo Renier, a former priest who founded the festival and is its executive director, worries that drying funds from the Philippine and foreign governments and corporate sponsors more inclined to spend for a Justin Bieber concert than the music of masters may mean the end to the annual concerts, held since 1975 at St. Joseph church in Las Piñas. This year’s event runs from Feb. 19-27.

As of last Wednesday, the eve of the festival’s 40th year, only a portion of the P3.2-million budget had been secured. The rest of the pledged donations had not yet been sent to the foundation that runs the festival, and ticket sales alone were not enough to fund the performances. After this year’s festival, the foundation’s reserves will be exhausted.

Article continues after this advertisementFunding crunch

Article continues after this advertisementOrganizers blame the funding crunch on the abolition of a government discretionary fund for lawmakers’ pet projects, belt-tightening by European embassies affected by the economic downturn in their countries, and less support from corporate sponsors more keen on involvement in pop concerts.

Without the festival, the unique sound of the bamboo organ—completed by Spanish priest Diego Cera in 1824—would have no venue to really shine, Renier said. “The bamboo organ is not just a piece of furniture with bamboo, but you have to hear it,” he said, as performers rehearsed music from Bach’s “B minor Mass” under chandeliers made of Capiz shells and bamboo.

The organ is also played during church services, but Renier said the festival is where it really shines, with renowned musicians bringing out its beauty. He said Cera was a genius who created a complete instrument and brought it to its ultimate level, gathering the pipes from nature and classifying them into related sounds.

“I guess you cannot go farther than what he did in the number of pipes, in the extension of the keyboards. Normally the keyboard ends at ‘do’—he made it up to ‘fa,”’ Renier said.

Swiss organist Guy Bovet, in his seventh year at the festival, said, “All the bamboo parts of the organ are very gentle, and reminds you a little of, I would say, a pan pipe, or something like a wooden flute.”

“If I pull this one, or this one, the sound will be very different,” he said, pulling on knobs to make different sounds. “It’s just like calling for one instrument of the orchestra or for another one.”

National cultural treasure

The organ has been declared a national cultural treasure and the festival organizers are confident the instrument will continue to have support from the Philippine government. Still, the eight-night festival—when the organ is accompanied by an orchestra, a choir and singers under the direction of noted conductors at the stone-and-wood church—is at risk due to the dwindling funds.

Renowned musicians from overseas come out of love, receiving minimal pay for the festival, which serves as a forum for musicians to meet, and as a training ground for local talent. Several former members of the Las Piñas boys choir, which performs at the festival, have gone on to pursue international careers in music and organ building after training in Europe.

The festival’s artistic director and resident organist, Armando Salarza, is a product of the boys choir, and has played the bamboo organ since he was 11. After high school, he was sent on a scholarship to study music in Graz in southeastern Austria. He did his postgraduate studies in Vienna, but came back in 1992 to share his talent with the younger generation in his hometown.

“It’s the only place in the Philippines where you hear this kind of music and with this kind of interpretation,” said Salarza, a professor of organ at the University of the Philippines.

More than just a festival

Throughout its existence, the festival has been mainly dedicated to Baroque music, which preceded classical, because the bamboo organ was built as a retro-18th century Iberian-style instrument. Salarza said such music is seldom introduced in local schools, with popular music most often heard in public places and on the airwaves. The challenge, he said, is to educate and expose children to it.

“We keep coming back because it’s a wonderful atmosphere, you find that nowhere else in the world, and the sound of the organ is magnificent,” said Jules Maate, a 53-year-old Dutch expatriate who attended the festival for the fourth time.

But more than just a festival, Renier said the annual gathering preserves heritage, revives forgotten Baroque music played on the bamboo organ and promotes excellence among local musicians.

“A nation does not need only entertainment, it needs values which are permanent: a sense for real beauty, appreciation of real artists, knowledge of its roots and listening to all the good things our ancestors were able to accomplish, and which we can admire in our heritage,” he said.

Melvyn and Paulette Marcial, a Filipino couple who attended the festival for the first time, said they enjoyed the concert and plan to return next year with their two sons. But whether there will be another festival for the children to listen to next year remains to be seen. AP