Tribal folk seek voice in Bangsamoro

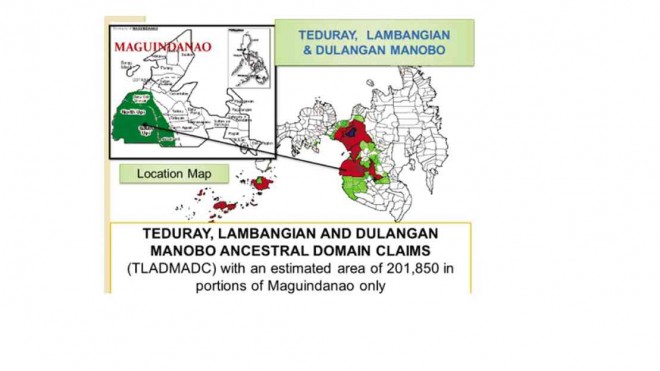

Map of the joint ancestral domain claims of the Teduray, Lambangian and Dulangan Manobo tribes. CONTRIBUTED BY TIMUAY JUSTICE AND GOVERNANCE

(First of two parts)

Edtami Mansayagan, an Arumanen Manobo, said he thought that if Mamalu were alive today, he would insist on the inclusion of indigenous peoples’ (IP) rights in the Bangsamoro Basic Law (BBL).

“Even during that time, a very long time ago, when his brother converted to Islam, he already insisted on an agreement that would ensure that the territory of his descendants would be respected,” Mansayagan said during the Mindanao leg of a consultation with the United Nations special rapporteur on indigenous peoples’ rights in Davao City on Wednesday, Jan. 21.

Mansayagan sits as member of the United Nations Expert Mechanism on the Rights of the Indigenous Peoples for Asia and the Pacific (UN EMRIP).

Mansayagan was referring to the story of brothers Mamalu and Tabunaway, legendary ancestors of the Islamized tribe of Maguindanao province and Mindanao’s non-Muslim indigenous peoples, whose peace pact hundreds of years ago non-Muslim IPs deem relevant now with the dawning of the Bangsamoro.

Article continues after this advertisementThe brothers inked a pact to respect each other’s territories after one brother, Tabunaway, had converted to Islam upon the arrival of Shariff Kabungsuan, said Timuay Labi Sany Bello, head of the supreme justice and governance body of the Teduray, one of the IP groups within the Bangsamoro area.

Article continues after this advertisementBello said the story about Mamalu and Tabunaway had been passed down to him by his grandfather who heard it from his father and his father’s father before him. As the new era of the Bangsamoro dawns in Mindanao, IPs like him deem relevant the peace pact between Mamalu and Tabunaway, so often recounted in their oral tradition, because the pact delineated and defined the territories of the descendants of the two brothers.

As Congress vows to prioritize the passing in March of the Bangsamoro Basic Law, which will govern the new juridical entity called Bangsamoro, IP groups within the Bangsamoro and contiguous areas continue to ask for provisions in the BBL that will recognize the ancient pact and their right to ancestral domain and self-determination.

But despite assurances from the government and the leadership of the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF), Teduray and Arumanen Manobo leaders said they felt that their concerns had been glossed over and continued to be ignored.

In the consultation with the UN special rapporteur on indigenous peoples’ rights, IP leaders in the Bangsamoro area said they were hoping for a last chance to be heard as Congress would resume session this week.

“For us, it is very important to include in the draft BBL a very clear policy on the delineation of ancestral domain,” said Timuay Alim Bandara, a Teduray leader.

“That’s why, in every consultation in Congress, we participate and submit our position,” he said.

He said the issuance of a certificate of ancestral domain title (CADT) for 300,000 hectares of ancestral land and 90,000 ha of foreshore areas had long been delayed.

Bandara said that even if the CADT was not issued prior to the passage of the BBL, IP rights should be recognized in the BBL “so we won’t have a problem once the ARMM (Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao) is dissolved to give way to the Bangsamoro.”