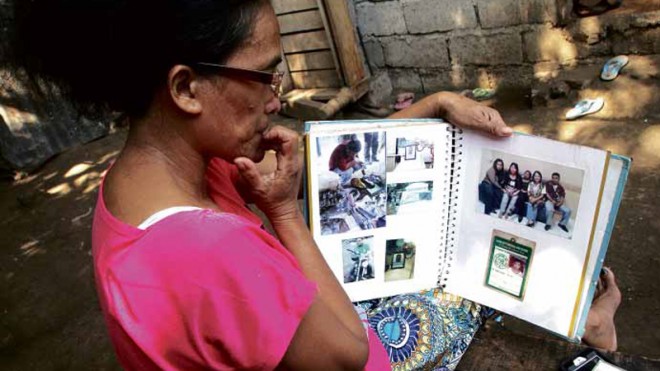

PHOTOGRAPHS AND MEMORIES Cathy Nuñez looks at photos of her son, Victor, who was one of 32

journalists killed in Ampatuan town,Maguindanao province, on Nov. 23, 2009. JB R. DEVEZA/INQUIRER MINDANAO

(Third of a series)

It is always like this, she said.

“He looked just like his father,” she said, gesturing toward the man opposite her.

“He wanted to build us a nice house on a lot big enough for houses for the families of his two other siblings. He was such a sweet boy. He would have turned 29 this year,” she said.

UNTV reporter Victor Nuñez was one of the 58 people, 32 of them journalists, who were killed in what is now known as the Maguindanao massacre on Nov. 23, 2009, in Ampatuan town, Maguindanao province.

Relatives and supporters of then Buluan Vice Mayor Esmael Mangudadatu were on their way to Shariff Aguak town in Maguindanao to file his certificate of candidacy for governor when they were blocked by armed men allegedly led by members of the Ampatuan clan.

Their bodies and vehicles were later found in hastily dug mass graves on a hill.

“They are demons,” Cathy Nuñez said, referring to her son’s killers.

Five years after the horrific attack on a group of women, journalists and plain passersby, Nuñez’s anger has not eased.

Trial barely moving

While the alleged brains behind the massacre—Andal Ampatuan Sr., Andal Ampatuan Jr. and Zaldy Ampatuan—and 109 of their followers have been arrested and charged in court, 84 other suspects remain at large.

And the trial in a Quezon City court is barely moving.

Nuñez is also angry about some developments in the trial. Just last month, the court granted bail to 41 suspects, although the amount was set at P200,000 for each count of murder, or P11.6 million for all 58 counts.

The court has been saddled with a host of petitions and challenges to testimony that, while within the rights of the accused, has the effect of hijacking the delivery of justice.

“I had high hopes at the beginning that President Aquino will give us justice,” Nuñez said, “but now I understand why people turn to armed rebellion.”

The ranks of witnesses are thinning and the families of the victims are either being threatened by armed goons or offered large sums in exchange for silence.

The slow delivery of justice is being complicated by the killings of witnesses, said Grace Morales, who lost her husband and a sister in the massacre.

“They were important in our quest for justice, but they were killed,” Morales said.

In Digos City, the family of victim Nap Salaysay is uninterested in any form of settlement, and hopes Mangudadatu will press the fight for justice.

“We don’t have money, we can do nothing but pin our hopes on him because he is powerful now,” Ernesto Salaysay, brother of Nap, said.

He denied talk that his family had settled with the Ampatuans and said the family now doubted the resolve of the other families, who suddenly turned cool to pressing the case.

“There was talk of payoffs, as much as P50 million, but we had not verified it,” Salaysay said.

“No amount of money can pay for the life of my brother. We will turn down even a shipful of cash,” he said.

Culture of impunity

In a homily during a Mass at the memorial to the victims in Masalay village, the massacre site in Maguindanao, Passionist priest Rey Ondap also bewailed the protracted wait for justice.

“I watched the readers, the children or relatives of the victims of the [Maguindanao] massacre. They have grown healthy, but justice [remains] elusive. I am growing old, too, and still no justice,” Ondap said.

Rhulie May Montaño, a daughter of victim Marife Montaño, couldn’t agree more.

She said she was 6 when she lost her mother. Now she’s 11 but none of the killers of her mother has been convicted.

“She will never come back. My mother is gone, and there is still no justice,” she said.

Australian Mike Dobbie, a representative of the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ), said five years of “zero justice” only meant that the justice system in the Philippines was “not working.”

“You have 58 people massacred and after five years we still don’t have any resolution, we still don’t have justice,” Dobbie said.

“The culture of impunity in this country is flourishing, especially when you have another 33 journalists killed during the Aquino administration,” he said.

Dobbie was referring to the killings of journalists and other critics of the government that remained unresolved.

Jane Worthington, IFJ Asia-Pacific acting director, lamented that in the five years that the trial has been going on, not a single conviction has been handed down.

“It is clear that the situation in the Philippines is dire and it is a concern for our colleagues around the world. It’s an issue that the whole world is watching,” she said at a news conference in Manila.

Mindanao journalists killed

In Mindanao alone, where more than half of all journalist killings in the country took place, the list of deaths since the massacre is getting longer: Ismael Pasigna (Dec. 24, 2009), Jessie Camangyan (June 14, 2010), Nestor Bedolido (June 19, 2010), Roy Gallego (Oct. 14, 2011), Alfredo Velarde (Nov. 11, 2011), Christopher Guarin (Jan. 5, 2012);

Aldion Layao (April 8, 2012), Rommel Palma (April 30, 2012), Nestor Libaton (May 8, 2012), Mario Sy (Aug. 1, 2013), Nanding Solijon (Aug. 29, 2013), Joash Dignos (Nov. 29, 2013), Tata Butalid (Dec. 11, 2013), Richard Najid (May 4, 2014), and Sammy Oliverio (May 23, 2014).

If the case against the massacre suspects continues to languish in court despite unrelenting pressure from local and foreign rights groups, the cases involving other journalist killings, in instances where perpetrators were later identified and charged in court, are faring much worse out of the spotlight.

Still at large

The case of Solijon, a broadcaster at Love Radio 107.1 Iligan City, is an example. He was shot by two motorcycle-riding men in Barangay (village) Buruun in Iligan. Witnesses later identified a city policeman, PO1 Pejay Capangpangan, as the motorcycle driver.

Capangpangan is a former bodyguard of Iligan Mayor Celso Regencia, who previously served as city police chief. The other suspect, identified in the course of a National Bureau of Investigation probe, was shot and killed a few days after the attack on Solijon.

A murder case was filed against Capangpangan in Iligan by the Regional State Prosecutor’s Office (RSPO) in February. It was first raffled to Regional Trial Court (RTC) Branch 5 under Judge Ali Balindong, who dismissed it in April, saying the panel of prosecutors created by the RSPO based in Cagayan de Oro City had no authority to file the case in Iligan.

Justice Secretary Leila de Lima ordered the refiling of the case and reaffirmed the authority of the RSPO. The case was then reraffled to RTC Branch 4 in Iligan under Judge Concordio Baguio, who issued a warrant for Capangpangan’s arrest on Sept. 9.

Baguio later inhibited himself from the case following a motion from the defense. The case is now in RTC Branch 6.

Capangpangan remains at large.

Common predicament

The delays in the Solijon case, as in the Maguindanao Massacre trial, are a common predicament in all cases of journalist killings, according to lawyer Santiago Goking Jr. of Free Legal Assistance Group, who is a former chair of the National Union of Journalists Cagayan de Oro City.

The concept of “guilt beyond reasonable doubt” also works in favor of the accused, especially in cases where the accused has resources to mount an effective legal defense, Goking said.

Add to that the lack of prosecutors—one of the many problems of the Philippine criminal justice system—and delay in the prosecution and resolution of cases is almost assured, he said.

In the meantime, all that Nuñez can do is cradle a powder-blue photo album on her lap, look at photographs of her slain son—a smiling Victor on a motorbike, Victor on TV reporting the news, a teenage Victor on a high-school identification card—and cry.–With reports from Julie M. Aurelio in Manila and Orlando Dinoy and Julie S. Alipala, Inquirer Mindanao

RELATED STORIES

Maguindanao massacre anniversary: Aquino reminded of poll promise

SC has taken ‘extraordinary’ steps for speedy Maguindanao massacre trial — Sereno

700 protesters call for end to impunity on 5th anniversary of Maguindanao massacre