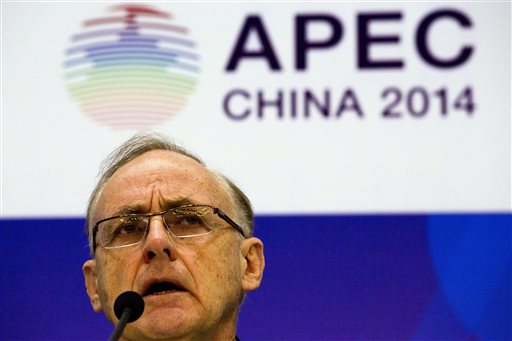

In this photo taken Thursday, Nov. 6, 2014, Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Secretariat Alan Bollard speaks about an initiative to setup an anti-corruption and transparency network between APEC members during a press conference ahead of the APEC Economic Leaders’ Week to be held in Beijing, China. AP.

BEIJING, China—China’s graft busters want foreign help in their “fox hunt” for corrupt officials who have fled the country and stashed their ill-gotten loot abroad, but misgivings about Chinese justice may deter the United States and other nations from wholeheartedly joining the chase.

When leaders of Asia Pacific countries meet Monday and Tuesday in Beijing, they are expected to endorse a network for member nations to share information on corruption cases and help recover assets that have been moved across borders illegally.

“We are setting up what is called an anti-corruption and transparency network,” said Alan Bollard, Asia-Pacific Economic Forum’s Secretariat executive director. “This group will try and bring together the actual operational people who will share information on particular cases, share information about how to get convictions and prosecutions and, if necessary, assets back as well.”

He said Beijing has initiated the plan, which also is backed by the United States.

That would be a major advance in China’s anti-graft campaign, which seeks to cut off the exit route of its corrupt officials. But cooperation with Western countries—especially U.S., Canada and Australia—may remain limited because of the ruling Communist Party’s control of the Chinese judicial system, its use of death as penalty for corruption, and doubts about whether extradited suspects will receive fair trials.

The three countries—all friendlier to Chinese emigres than Europe—have yet to sign extradition treaties with Beijing.

“So long as China is not a democratic country with transparent and trusted institutions … this reservation about cooperating with it is likely to linger,” Linda Lim of the University of Michigan Ross School of Business said in an emailed response to questions from The Associated Press.

Beijing has estimated that since the mid-1990s, 16,000 to 18,000 corrupt officials and employees of state-owned enterprises have fled China or gone into hiding with pilfered assets totaling more than 800 billion yuan ($135 billion).

Corruption, long pervasive in China, has eroded the public’s trust so much that the Communist Party considers it a threat to its grip on power. President Xi Jinping has made fighting corruption a priority.

This year the Chinese authorities launched Operation Fox Hunt, targeting corrupt officials who have absconded abroad. To emphasize that high officials are fair game, Xi has said the campaign would beat “tigers” as well as swatting lower-level “flies.”

“We hope we can receive support and coordination from the global community, especially in the process of tracking down fugitives and illegal profits,” Foreign Minister Wang Yi said ahead of the APEC conference. “We hope that all relevant parties could support us and not become the safe havens for those fugitives.”

By the end of October, the overseas sweep had brought back 180 suspects—mostly from Asia, Africa and South America, the Public Security Ministry said.

However, China is seeking more cooperation with the U.S., Canada, and Australia, because they “have the highest concentrations of corrupt officials,” said Wang Yukai, an anti-corruption expert at the Chinese Academy of Governance. “So it will be of great significance if China can build cooperative mechanisms with these countries to capture corrupt officials on the run and recover some economic losses.”

But these countries are popular among corrupt Chinese officials for a reason. Their robust legal systems and concerns over possible judicial abuses in China have made their governments hesitant to repatriate Chinese citizens, or those who have gained residency or citizenship. The countries have collaborated with China in the past, but only on a case-by-case basis.

Entrepreneur and accused smuggler Lai Changxing was deported from Canada in 2011, but only after a 12-year extradition battle. China, which considers corruption to be a capital crime, agreed not to pursue the death penalty in Lai’s case.

In 2004, the United States sent back Chinese bank executive Yu Zhendong, accused of embezzling $485 million with other defendants, on the condition that Yu would not be tortured or given the death penalty, which is common in China even for less serious corruption cases.

“For the West, which worships the rule of law, the greatest form of corruption is abusing one’s power and infringing on civil rights,” wrote Yang Hengjun, a former Chinese diplomat who is now an independent writer in Australia. He noted that corrupt Chinese officials can claim to be victims of political persecution and added that “differing definitions of what constitutes ‘corruption'” have complicated cooperation between China and some countries.

Despite the complications, more collaboration is underway.

A statement by Australia Federal Police said it assists China in tracing and restraining illicit assets in Australia and works with Beijing to “enhance bilateral cooperation on money laundering, remitters and economic fugitives.”

Canada and China are in the process of signing and ratifying an inter-governmental agreement on the sharing of forfeited assets and the return of property, said John Babcock, spokesman for Canada’s Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development.

In an editorial published Monday on the website of the Chinese-language financial media group Caixin, David Luna, senior director of anti-crime programs at the U.S. State Department, said Washington is willing to work with Beijing on its anti-corruption efforts while U.S. law enforcement cracks down on American companies bribing foreign officials. He suggested that senior anti-corruption officials from member countries meet.

John Ciorciari, assistant professor of public policy at University of Michigan-Ann Arbor, said there will be limits to such cooperation. He said an extradition treaty between China and the U.S. is unlikely “due to abiding U.S. concerns about China’s human rights record and due process protections.”

The United States can repatriate Chinese citizens in accordance with the U.N. Convention Against Corruption or deport them on violation of immigration rules, “yet the United States is not apt to send back suspects when it believes they will face politicized prosecution and sham trials,” Ciorciari said.

“The challenges China faces getting U.S. help for the ‘fox hunt’ have at least as much to do with a political trust deficit as a lack of legal mechanisms for repatriation,” he said.

RELATED STORIES

Apec preparations: China bans burning clothes of dead

Japan to call for summit with China’s Xi at Apec