Regime of Marcoses, cronies, kleptocracy

MANILA, Philippines–“We practically own everything in the Philippines—from electricity, telecommunications, airline, banking, beer and tobacco, newspaper publishing, television stations, shipping, oil and mining, hotels and beach resorts, down to coconut milling, small farms, real estate and insurance,” said Imelda Marcos, talking to the Inquirer in 1998 while she disclosed her plan to file an intervention suit against the cronies of her husband.

Imelda said the Marcos family accumulated its wealth “without dipping into government coffers.”

Former Senate President Jovito Salonga challenged Imelda’s claim, saying that the Marcoses had started raiding the government coffers barely two years into the first term of President Ferdinand Marcos in 1965, with his wife using intelligence funds to finance her foreign trips as first lady and stashing part of the money in Swiss banks.

In his book “Presidential Plunder: The Quest for the Marcos Ill-gotten Wealth,” Salonga enumerated the ways by which the Marcoses acquired and safeguarded ill-gotten wealth.

Modus operandi

Article continues after this advertisementHe said these included the creation of monopolies in certain vital industries and placing them under the control of Marcos cronies or associates, citing the sugar industry under Roberto Benedicto and coconut industry under Eduardo Cojuangco.

Article continues after this advertisementAnother technique was the outright takeover by Marcos relatives or cronies of large public or private enterprises with nominal amounts as consideration. Case in point: the business and assets of National Shipyard and Engineering Co. and other related government-owned or -controlled entities were taken over in 1972-1973 by Baseco, a private corporation dominated by Marcos and Alfredo “Bejo” Romualdez, a brother of Imelda.

“That’s how [Imelda] and her husband raided government funds,” said Salonga, who served as the first chair of the Presidential Commission on Good Government (PCGG).

Kleptocracy

The PCGG was created in 1986, three days after the inauguration of Corazon Aquino as President, to recover the ill-gotten wealth of Marcos, his immediate family, relatives and cronies.

Because of the massive ill-gotten wealth amassed by the Marcos family and its cronies, the Marcos regime has been called a kleptocracy (from the Greek words for thief and rule).

In hearings in 1986, then US Rep. Stephen Solarz said the Marcos couple looted the Philippine treasury of millions of dollars to buy real estate in the United States. Solarz accused Marcos of running a kleptocracy and enriching himself and his wife at the expense of his country’s citizens.

According to a 2003 ruling of the Supreme Court, assets presumed to be ill-gotten include Marcoses’ wealth in excess of their total legal income of around $304,000 from 1965 to 1986.

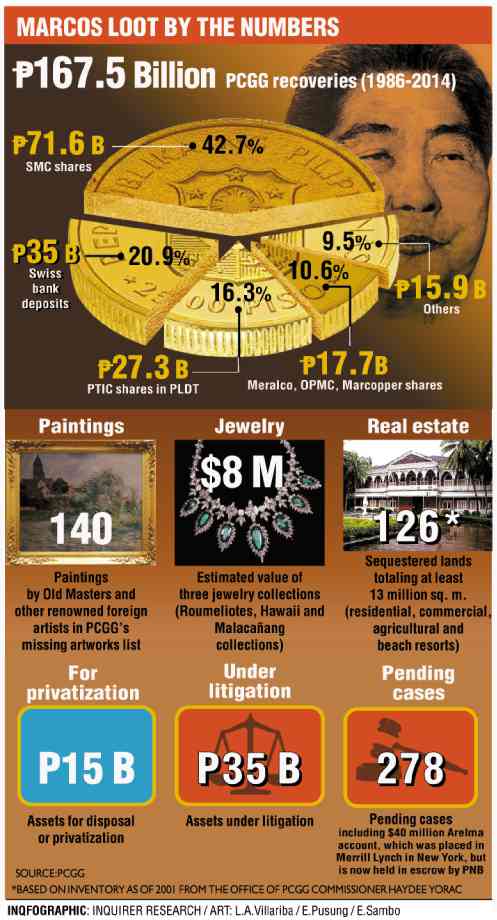

Almost 30 years since its creation, the PCGG has recovered P167.5 billion, or about $4 billion, less than half of the $10-billion fortune believed to have been amassed by the late dictator, who stayed in power for 21 years.

The amount recovered is the aggregate cash value, as of February, of all accounts hidden in local and foreign banks, commercial and residential properties, shares in companies here and abroad, artworks and valuable personal effects that had been surrendered to the PCGG or awarded by various courts in the Philippines, Switzerland and the United States.

SMC shares, coco levy

The biggest single recovery (40 percent of the total) was in 2012—P71.6 billion from 24-percent block of San Miguel Corp. (SMC) shares, including dividends and accrued interest, which the government claimed were acquired with coconut levy funds.

The 24 percent was part of the 47-percent block of SMC shares sequestered by the PCGG on the ground that these were illegally acquired by the dummies of Marcos using funds from a tax imposed on coconut farmers from 1973 to the 1980s.

The Supreme Court ruled in 2012 that the 24 percent (originally 27 percent but diluted and reduced because of SMC’s expansion) belonged to the government in trust for the country’s coconut farmers.

But the high court ruled that the remaining 20-percent block claimed by businessman Cojuangco had been legally acquired by the crony whom Marcos had appointed as administrator of the levy funds.

Swiss bank deposits

The Swiss bank deposits of the Marcoses constituted a fifth of the recovery, or an estimated P35 billion, which includes the P1.3 billion ($29 million) recovered in February from the WestLB Singapore accounts.

The WestLB Singapore accounts were part of the ill-gotten wealth that the late strongman kept in various Swiss bank accounts under dummy foundations. In 1997, the Swiss Federal Supreme Court ordered that these deposits be returned to the Philippine government.

In its 2003 ruling, the Philippine Supreme Court forfeited some $683 million in Marcos Swiss deposits in favor of the government. It said Marcos and his wife could not have legally acquired the assets with their legitimate income.

“In sum, the evidence offered for summary judgment of the case did not prove that the money in the Swiss banks belonged to the Marcos spouses because no legal proof exists in the record as to the ownership by the Marcoses of the funds in escrow from the Swiss Banks,” the tribunal said.

PLDT, Meralco

A total of P27.3 billion of the recovered assets came from Philippine Telecommunications Investment Corp. (PTIC) shares in Philippine Long Distance Telephone Co. (PLDT). The Supreme Court declared in January 2006 that the PTIC shares in PLDT were part of the Marcos ill-gotten wealth as these were registered in the name of Prime Holdings Inc., an alleged dummy firm of Marcos.

The amount from the sale of shares in Manila Electric Co. (Meralco), Oriental Petroleum and Minerals Corp., and Marcopper Mining Corp. accounted for P17.7 billion while other recoveries amounted to P15.9 billion. Some P50 billion worth of assets are either tied up in litigation or are up for privatization.

The latest privatization effort by the PCGG included three properties forfeited from the late Jolly Bugarin, who served as a National Bureau of Investigation director.

Real estate

In September, the auction of the properties at North Greenhills, Valle Verde III and Capitol Hills attracted 29 bidders and earned a combined P157.7 million, 38 percent higher than the combined floor price of P114.3 million.

The Mapalad property, a commercial and residential lot on Roxas Boulevard in Parañaque surrendered to the government in 1986 by the late Marcos crony Jose Y. Campos, was sold for P247.11 million in March 2013.

The government has also scored major legal victories over the past 15 months.

In March, the Supreme Court affirmed its previous forfeiture order on some $40 million on Marcos’ secret account in New York for being part of his ill-gotten wealth.

Arelma assets

In the final ruling dated March 12, the Supreme Court’s Special Second Division rejected the appeal of former first lady, now Ilocos Norte Rep. Imelda Marcos, and son Sen. Ferdinand Marcos Jr., to overturn a 2009 forfeiture order on the Arelma S.A. assets with the investment firm Merrill Lynch.

Arelma is a Panamanian corporation believed to have been one of the dummy firms used by Marcos to hide ill-gotten gains.

With the recent decision, PCGG Chair Andres Bautista said the government was optimistic that it would be able to enforce the decision in the United States and recover the funds, which have been tied up in litigation since 2000. The case is pending in the New York Court of Appeals.

Monet painting

In January, Vilma Bautista, Imelda Marcos’ New York-based personal secretary, was sentenced by the New York State Supreme Court to up to six years in prison after finding her guilty of scheming to sell a $32-million Claude Monet painting and tax fraud.

The 1899 art work, “Le Bassin aux Nymphease,” or “Japanese Footbridge over the Water-Lily Pond at Giverny,” from the French painter’s “Water Lilies” series, was among the ill-gotten assets the government was seeking to reclaim from the Marcoses. The Monet disappeared when the Marcos family fled into exile.

Last year, the Supreme Court ruled with finality that the government owned the shares of Cojuangco in United Coconut Planter’s Bank, which became the depository of the coco levy funds. The high court also ruled that the fund should be used for the benefit of the coconut farmers.

The PCGG recoveries serve as a source of funds for some social justice measures.

Land reform

Based on the Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Program (CARP) law, funds recovered by the PCGG shall be remitted to the Bureau of the Treasury to serve as additional funding for the implementation of the program.

As of 2013, the PCGG reported that it had provided some P87 billion to CARP, the centerpiece program of the first Aquino administration, since its inception.

The amount was used to finance rural electrification, construction of farm-to-market infrastructure, post-harvest facilities, school buildings and potable water supply systems. It also financed the provision of credit assistance and scholarship grants, and the conduct of extension and training services.

Proceeds from the SMC shares have been allocated for the coconut industry, while P10 billion of the money recovered from the Swiss accounts has been earmarked as the principal fund for Republic Act No. 10368 for the compensation of victims of human rights violations during the Marcos regime.

Sources: Inquirer archives, pcgg.gov.ph

RELATED STORIES

What Went Before: The $35M claim on alleged Marcos wealth

Imelda Marcos aide gets jail term over Monet sale