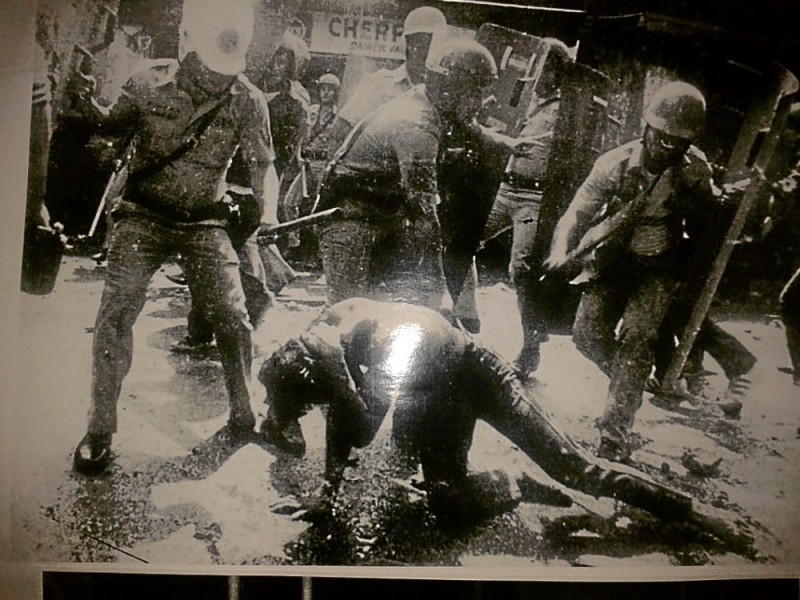

THIS PHOTO of police brutality on protesters is among those displayed in the exhibit, “Himagsik at Protesta,” put up by Karapatan at the University of the Philippines Library until Sept. 21 for the 40th anniversary of the declaration of martial rule. PHOTO REPRODUCTION BY TONETTE OREJAS

Outside a dull, unremarkable building at the University of the Philippines (UP) in Quezon City, a line of weary, graying folk brave the heat and the long wait to tell their stories from four decades ago.

The elderly walk with difficulty with their canes, their faces seemingly etched with the weight of their memories. The younger ones, the families of those who did not make it, are here because they want justice and recognition.

The wait is made a little bearable with plastic chairs and a sunshade—and the company and instant camaraderie of other survivors they met only on that day.

“Sometimes, those from the provinces arrive as early as dawn to line up. We try to accommodate them all as best we can,” said Lina Sarmiento, a retired two-star police general who chairs the Human Rights Victims Claims Board (HRVCB).

Reparations, remuneration

The HRVCB is in charge of processing the claims of human rights victims of martial law as mandated by Republic Act No. 10368, or the Human Rights Victims’ Reparation and Recognition Act of 2013, which recognizes and provides reparations for the victims.

The government is providing about P10 billion to remunerate the rights abuse victims of the martial law regime of the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos.

Aside from the financial remuneration, the HRVCB is also considering the possibility of nonmonetary help like PhilHealth coverage, livelihood training and scholarships for the heirs, etc.

The filing of claims began on May 12 and will end on Nov. 10, after which the board has until 2015 to finish the validation, evaluation, investigation and adjudication of the cases.

As of Thursday, the board had received 13,437 claims from its caravans, regional desks and its main office on the UP campus.

30,000 abuse victims

At the HRVCB’s main office on the ground floor of Virata Hall, staff manning a row of cubicles at one end attend to the claimants who carry with them the yellowed documents that constitute proof of their claims.

At the other end of the hall are the board’s office and that of Sarmiento, both almost bare of furnishings except for a few tables and chairs and piles of folders.

Here, a maximum of 365 claims are processed and encoded daily by Sarmiento’s staff, who assist human rights victims in the painstaking work of accomplishing the forms and patiently listen to their stories.

The HRVCB expects 30,000 or more claims to be filed, although board member Aurora Parong said they were not limiting themselves to this figure.

“We are not setting the limit at 20,000 or 30,000. We will welcome more claimants out there if there are more,” she said.

The board’s task is made even more daunting as it has a staff of but 30 people, with only five lawyers and four paralegals, as the law that created the HRVCB prescribes. The application period is only up to six months, as also indicated in the law.

“We cannot go beyond what is prescribed in the law since we are only implementing it,” Sarmiento said.

Caravans around country

To make the application process easier for the victims, the HRVCB has been conducting caravans around the country where victims can file their claims.

The first phase covered the cities of Angeles, Calbayog, Tacloban, Iloilo, Cebu, Bacolod, Butuan, Cagayan de Oro, Cotabato, Davao, Zamboanga, San Fernando in La Union province, Baguio, Tuguegarao and Lucena.

The second phase, which is being carried out now, involves visiting the cities of Jolo, San Jose, Roxas, Sorsogon, Catarman, Borongan, Dumaguete, Batangas, Bacolod, Bangued, Kalinga, Ilagan, Bayombong, Pagadian, General Santos, Tagum and Malaybalay.

Aside from the caravans, there are the five regional HRVCB desks that have been set up in the Commission on Human Rights offices in the cities of Legazpi, Tacloban, Iloilo, Davao and Cotabato.

“During the caravans, it was in these regions that we received so many claims, around 1,000 per area. In other areas, there were practically no claimants,” Sarmiento said.

Each of the regional desks will have at least one paralegal staff.

“The staff will be able to accept complete documents, encode and scan documents, and issue acknowledgment receipts to the applicants like what is done in the main office,” Sarmiento said.

The board is focusing its efforts on accepting the claims given its limited manpower, although it has begun validating some of the claims as well.

Speak up and be heard

Sometimes Sarmiento herself reads some of the claims and the victims’ stories of abuse.

“You will be touched by their experiences. But some only write one sentence to describe their experience. We urge them to really tell their stories, because their experiences will be memorialized and used to educate others on that part of our history,” she said.

The claimants’ stories will form part of a museum on martial law that is to be set up as mandated by law.

Parong, who is a rights abuse victim herself, urged other victims to speak up and have their experience heard and documented.

“We should tell our stories and the struggle against the dictatorship. We hope all the victims will file their claims so we can show what happened to the human rights victims,” she said.

While the more prominent claimants will have an easier time filing their applications because of existing documentation, the more obscure victims may have some difficulty in filing their claims.

Parong said undocumented victims may obtain affidavits from two knowledgeable persons who can testify on their case.

“Human rights is very important. You should know your rights and assert it, and don’t be silent if it is violated. You should also help others if you think their rights are being violated,” she said.

Heartless fixers

She lamented that unscrupulous fixers were making the rounds of various communities, offering to help applicants file their claims for a fee ranging from P600 to P1,500.

She said filing a claim at the HRVCB is free of charge.

“These fixers are heartless. They are trying to dupe human rights victims, some already in the twilight of their years, some have nothing left. I have heard of fixers wanting a 10-percent cut [from whatever the victim will get],” Parong said.

Parong and the other board members sometimes have to help in the processing of the claims during times when they are shorthanded.

“It’s the least we can do,” she said.

The staff work really long hours, their day beginning as early as 8 a.m. and sometimes ending shortly before midnight.

Sarmiento acknowledged there had been some opposition to her appointment to the board. She declined to elaborate as the case is already in the Supreme Court.

“For me, I will work as I am tasked to do. And my task is to ensure that these human rights victims are recognized in our history,” she said.

RELATED STORIES

Rights compensation board vows to expedite processes for martial law victims

How much is suffering under Marcos worth?

PCGG recovers $29M from Marcos loot

What Went Before: Marcos Swiss deposits