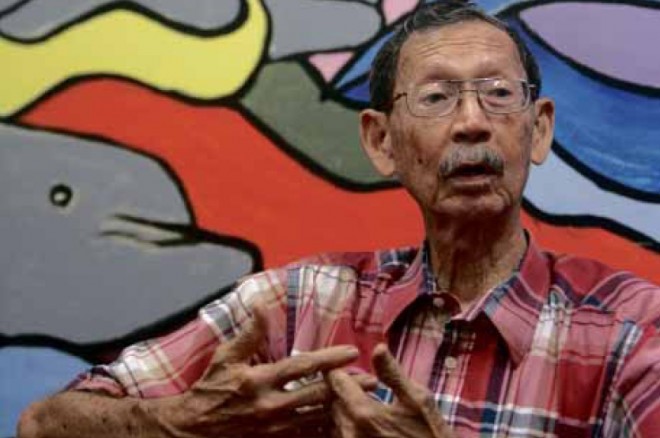

GOMEZ: “Once you destroy your reefs, you’re going to change the wholemarine ecosystem.Our oceans will change. So this is not just climate change, this is global change. ” NIÑO JESUS ORBETA

With global pollution and destructive fishing practices continuing to destroy coral reef ecosystems, it is a wonder how the renowned marine scientist and University of the Philippines (UP) professor emeritus Edgardo D. Gomez can remain optimistic about the future.

The new National Scientist awardee, who fell in love with the sea during a high school field trip, has kept the outlook that has carried him through four decades of conservation work alongside the world’s top coral reef scientists while leading the next generation of outstanding Filipino marine scientists.

Opportunities in adversity

The 75-year-old Gomez showed how he would rather focus on seeing opportunities in adversity in a lecture he delivered in China a few months ago.

He used a recent Inquirer photo of the Malvar Reef in the West Philippine Sea showing a Chinese fishing vessel with a backhoe attached to it.

The Chinese fishing vessel apparently used the backhoe to harvest endangered giant clams, destroying precious corals in their wake.

These are the same species of giant clams in the country’s waters that Gomez saved from extinction three decades ago.

“I said, all the giant clams in the South China Sea have been fished out, there’s nothing left there. A lot of people are destroying the reefs and over-harvesting the clams. If you’re destroying the reefs, who’s going to repair them?” Gomez recalled in an interview at the UP Marine Science Institute in Diliman, Quezon City.

He said he next showed his audience a photo of hundreds of giant clams being grown in the MSI’s marine laboratory in Bolinao, Pangasinan province. The laboratory-grown giant clams will eventually be transplanted in the sea to restock the dwindling population.

“I said, we are producing giant clams in the Philippines. Just to change the mindset, I said, instead of destroying, why don’t we restore and repopulate the taklobo? Why don’t we restock the South China Sea?” Gomez said.

“I told them we have the technology to repair reefs, we have manuals. Why don’t we repair the reefs?” he continued.

Get scientists together

The upshot was that someone in the audience invited him to go to Taiwan to conduct a workshop on giant clams.

“It’s an opportunity that I see opening. That maybe, instead of the military and the politicians arguing, let’s get the best scientists to work together to help our environment and restock our reefs,” he said.

According to Gomez, he was just looking at opportunities that others perhaps have not thought of.

“We’ll find a way and we’ll repair it. We’re not doing this so you can destroy. No, no, you stop destroying. But we’ll enhance. We’ll produce more,” he explained.

Pioneering work

Gomez was recently proclaimed a National Scientist in recognition of his pioneering work in the development of marine science in the country, coral reefs conservation and marine invertebrate reproduction.

In the 1970s, he spearheaded the first national-scale assessment of coral reefs damage undertaken anywhere in the world. The work led to worldwide conservation initiatives.

His researches have become the basis for the management and conservation programs of the country’s marine resources. His work on marine invertebrates led to the rescue of the giant clam from extinction.

Gomez, however, is proudest of having built the UP Marine Science Institute, literally from scratch, into a world-class research and teaching institution that has gained recognition for Filipino marine scientists in the international scientific community.

He credits positive attitude with the ethic for hard work and excellence for the success, “and because the planets and the stars were aligned.”

Fate indeed must have stepped in as Gomez did not immediately go into marine science although he would have wanted to.

“I had an interesting biology teacher [in high school],” he said, recalling a fond memory of a seashore field trip as a high school student at De La Salle.

After graduating summa cum laude from De La Salle University with a degree in education (major in social sciences and English) in 1962, he taught at his alma mater’s high school and later became dean of student affairs of De La Salle School in Bacolod City.

For his postgraduate studies, Gomez earned a master’s degree in biology from St. Mary’s University in Minnesota in 1967.

And then he saw an advertisement for doctorate scholarships from the National Science Development Board (NSDB), the precursor agency of the Department of Science and Technology. On the NSDB scholarship, he earned his doctorate in marine biology in 1973 from the renowned Scripps Institution of Oceanography at University of California in San Diego. He also learned scuba diving when he was at Scripps.

Mini-Scripps in PH

Gomez said the efficient, professional and scientific culture in the institution impressed him.

“And another thing, everybody helped everybody else. There was no marking of territory, no professional envy. Everybody worked together. I thought, wouldn’t it be nice if we have a mini-Scripps in the Philippines?” he said.

As it happened, when he returned and was hired by UP as a professor of marine biology in 1974, he was also given the added task of putting up a marine science center.

“UP had a dearth of marine scientists and wanted to start a marine science center. So here I came, willing to do whatever, so they offered me to do the job.

“They gave me two sheets of paper. ‘Here is the marine science center.’ No money, no equipment, no personnel, no office. I had to start from scratch literally,” he recalled.

Imparting the same culture ingrained in him during his postgraduate studies, Gomez also required of his faculty and graduate students recruits that they excel and publish their work in top scientific journals.

At first, the funds to support their research projects were hard to come by.

“In the 1980s, I would write a research proposal for P25,000. If I got P80,000, that was already a lot. Now some of my colleagues have research projects that run into P80 million,” Gomez said.

With Gomez at the helm for two decades, from 1974 to 1994, the UP Marine Science Institute became the top research institute in the country and in Southeast Asia. Its scientific papers and research projects recognized internationally.

Gomez’s own research has been much cited in scientific circles. He has also led not only the country but the region in global collaboration efforts on marine conservation.

In 1993, Gomez was elevated to the National Academy of Science and Technology (NAST), the country’s top advisory and recommendatory body on issues involving science and technology.

Gomez retired from teaching in 2005, when he was named UP professor emeritus for his outstanding work as a scholar.

Landmark study

One of his recent notable works dealt with the phenomenon of ocean acidification.

Gomez is one of the authors of a landmark study in 2007 on the phenomenon of ocean acidification, which found that too much carbon dioxide emissions are being absorbed by the oceans triggering a chemical reaction that causes water to be more acidic, which in turn affects marine life.

One such effect is the weakening of the reef structures.

“So the reefs of the future will not be as strong, as sturdy as the present reefs. What this means is our coral reefs will continue to degrade, our reefs will be weaker, and our reefs will eventually vanish,” Gomez said.

“Once you destroy your reefs, you’re going to change the whole marine ecosystem, the coastal ecosystem. Our oceans will change. So this is not just climate change, this is global change. This is happening,” he said.

Practicing botanist

But Gomez remains upbeat, saying Filipino scientists have opportunities opened to them to collaborate in global issues.

In the same way that he protects the marine rainforests, Gomez is as relentless as a practicing botanist in cultivating Philippine tree species.

“We also cannot have trees overnight. It takes decades before you can harvest lumber. That’s the same way with the giant clams. But you must come up with a system so that you can grow them. Otherwise we won’t have any more forests,” he said.

RELATED STORIES

Marine scientist pursues 47-yr study, uses of seaweeds

At 84, Silliman biologist still busy with marine research

Marine scientists leave for Tubbataha