Forensic pathologist Raquel Fortun talks about the science of handling and identifying dead bodies in mass disasters

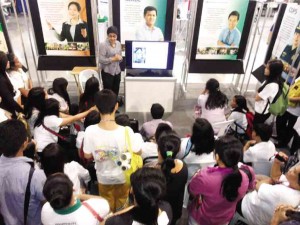

“Think morbid,” renowned forensic pathologist Dr. Raquel Fortun told the students huddled in front of her as a monitor showed photos of dead bodies lining the road in the grim aftermath of Supertyphoon “Yolanda.”

The students cringed. Some looked away when a black-and-white, full-body photo of a dead toddler was shown. They turned their attention back to Fortun only when she started talking about how hard it was to try and identify the bodies so they could be turned over to the right families.

A University of the Philippines professor and Metrobank Foundation Outstanding Teacher in 2006, Fortun was speaking at a forum sponsored by the foundation during the recent National Science and Technology Week (NSTW) organized by the Department of Science and Technology.

Identifying dead bodies is a science, said the forensic expert who led a team composed of personnel from the Department of Health, International Red Cross and Asia Foundation in Yolanda-hit Leyte and Samar provinces.

“Do you have dental records or a file with your fingerprints on it?” she asked her young audience. Dentures, DNA and fingerprints were still the best ways to identify people, she said. Prosthetic devices, like hip replacements, could also be significant as they had serial numbers.

“Something else that may be unique to you could also help, like birthmarks or a very distinct tattoo,” Fortun said. “But you have to remember that our bodies will not always be in perfect, preserved condition.” Disasters could mangle bodies in many ways, she cautioned.

She said that being able to tell a dead person’s gender, height and age bracket increased the chances of correct identification. Things worn by the deceased like clothes and jewelry should also be noted down. But no matter how thorough the file, she said, it would be useless without a record to compare it to.

Two kinds of documents are needed to positively identify a dead body, according to Fortun. Postmortem documents are accomplished by forensic experts examining a body, while antemortem forms are filled out by interviewing family, relatives or friends to get a description of the person they are looking for.

In theory, she said, the process of identification is rather straightforward and easy, but in the aftermath of a disaster where there are thousands of bodies, it is almost impossible to know

who is who if no system is in place.

She said the Philippines did not actually have a system or one specific responding agency “unlike other countries that have facilities, equipment and people who take charge of the dead in times of disasters.”

The responsibility is divided between the National Bureau of Investigation and the Philippine National Police. In the case of a natural disaster, the NBI is in charge. If it is a man-made catastrophe or an accident, like a plane crash, the PNP takes the lead.

But neither the NBI nor the PNP had the resources or the expertise, said Fortun. “They don’t even have body bags.”

After Yolanda, which claimed more than 6,000 lives, there should be an organized system of collecting bodies, she said. “Where should the bodies be brought and stored for examination? ”

In Tacloban City, officials agreed to keep the body bags in a cemetery but there was not enough space so some ended up on the road.

Fortun admitted they conducted a very limited external examination and most of the victims had nothing with them except the clothes they were wearing and some money in their pockets.

Identifying disaster victims and giving them back to their families, Fortun said, was not just a standard operating procedure. It was also a way of giving their surviving relatives a sense of closure so they could move on.

“If only the people in Yolanda-hit areas had thought morbid thoughts and perhaps had worn their IDs, identifying them wouldn’t have been as hard,” Fortun said.

The forum on disaster victim identification was the last in a series of talks at the Metrobank Foundation booth. Four other MBFI awardees discussed various real-life science topics.

Dr. Irma Makalinao, an outstanding teacher, talked about scientific issues like biotechnology. Sgt. Eugene Padilla and M/Sgt. Salvador Buenaobra Jr., both outstanding soldiers awardees, demonstrated how to make simple equipment like jungle antennae and portable runway lights, from limited resources. Noell El Farol, an art and design excellence awardee, showed the uses of science in the arts.

MBFI also had a Dream Exhibit and a Brain Bowl Challenge where students could answer math problems culled from the Metrobank-MTAP-DepEd Math Challenge and win prizes on the spot.