P

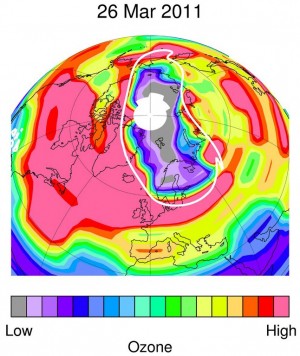

An image released on October 2, 2011 by NASA shows Ozone at about 20 km altitude, near the peak of the ozone layer in the lower stratosphere, in late March 2011. Red colors represent large ozone amounts, purple and gray colors (over the north polar region) represent very small ozone amounts. The white line marks the area within which chemical ozone destruction takes place. Worried scientists said Sunday, March 9, 2014, they had found four new ozone-destroying gases in the atmosphere, most likely put there by humans in the last 50-odd years despite a ban on these dangerous compounds. AFP PHOTO/NASA/JPL-CALTECH

ARIS—Worried scientists said Sunday they had found four new ozone-destroying gases in the atmosphere, most likely put there by humans in the last 50-odd years despite a ban on these dangerous compounds.

It is the first time since the 1990s that new substances damaging to Earth’s stratospheric shield have been found, and others may be out there, they said.

“Our research has shown four gases that were not around in the atmosphere at all until the 1960s, which suggests they are man-made,” the team from Europe and Australia wrote in the journal Nature Geoscience.

They analyzed unpolluted air samples collected in Tasmania between 1978 and 2012, and from deep, compacted snow in Greenland.

“The identification of these four new gases is very worrying as they will contribute to the destruction of the ozone layer,” added a statement from the team.

“We don’t know where the new gases are being emitted from, and this should be investigated.”

Three of the gases are chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs)—a group that includes chemicals traditionally found in air conditioning, refrigerators and aerosol spray cans but banned under the Montreal Protocol.

The fourth is a hydrochlorofluorocarbon (HCFC), part of a closely related group of compounds, which replaced CFCs but are being phased out.

More than 74,000 tonnes of the four newly identified gases had accumulated in the atmosphere by 2012, said the team.

This is very small compared with peak emissions of CFCs in the 1980s of more than a million tonnes per year.

Riddle of the source

“However, the reported emissions are clearly contrary to the intentions behind the Montreal Protocol, and raise questions about the sources of these gases,” the team wrote.

Two of the gases, one CFC and the HCFC, are still accumulating.

Previously, seven types of CFC and six of HCFC were known to contribute to ozone destruction.

CFCs, the main cause of the hole in the ozone layer over Antarctica, are man-made organic compounds made of carbon, chlorine and fluorine.

They were phased out from 1989, followed by a total ban in 2010.

HCFCs, CFC-like compounds that also include one or more hydrogen atoms, are less ozone-damaging but contribute to climate change by trapping more of the Sun’s heat in the atmosphere.

The ozone layer comprises triple-atom oxygen molecules that are spread thinly in the stratosphere.

It plays a vital role in protecting life by filtering out ultraviolet rays that can damage vegetation and cause skin cancer.

In high latitudes in the Southern Hemisphere, where the ozone layer is damaged or subject to seasonal fluctuations, people are advised to cover exposed skin and wear sunglasses.

Possible sources for the new gases include chemicals used for insecticide production and solvents for cleaning electronic components, said the researchers.

Concentration differences between the samples suggested the dominant source was in the industrialized Northern Hemisphere, they added.

Study co-author Johannes Laube from the University of East Anglia’s School of Environmental Sciences said the ozone layer stopped thinning from the late 1990s and there were signs of it starting to recover.

“As many ODSs [ozone-depleting substances], and especially CFCs, take a long time to break down once released into the atmosphere, it will be many decades until it will fully recover,” he told AFP.

“Provided we do not have further unpleasant surprises.”

Martyn Chipperfield, a professor of atmospheric chemistry at the University of Leeds in northern England, said the low concentrations of the four gases “do not present concern at the moment.”

But, he added, “the fact that these gases are in the atmosphere and some are increasing needs investigation.”—Mariette Le Roux

RELATED STORIES

Ozone pact helped cool the planet – study

Ozone layer faces record 40% loss over Arctic