Even an image believed to be powerful and miraculous like the Black Nazarene of Quiapo needs an army of protectors.

These devout guardians come from an all-male group of volunteers who call themselves Hijos del Nazareno (Sons of the Nazarene). They spring back to action for Thursday’s traslacion, the annual grand procession that takes the image through central Manila, facilitating mass veneration while keeping it safe from the crushing waves of devotees.

(The procession starts after the 6 a.m. Mass from Quirino Grandstand to Quiapo Church. See route on this site.)

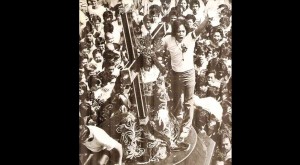

The Hijos form the crew who man the carroza bearing the holy image, performing a special task: Catch balled-up handkerchiefs and towels tossed by the devotees, have these items “blessed” through a quick dab on the statue, then throw them back to the crowd, hoping they are returned to their owners.

But the hardest job is on the ground, where other teams serve as navigators and marshals, pulling the carriage by two 50-meter-long ropes and clearing a path through the fanatic mob.

“Every year it gets harder to control the crowd because more and more young people are joining and they are becoming really aggressive,” said the group’s president, Arnel Irasga.

Ideally, only about four members should be assigned on top of the carriage, Irasga said. But now up to 25 men are needed to surround and secure it because of the sheer number of devotees who want to climb over, some determined to hug the Nazarene, others after its hair.

“There were times when people threw bottled water at us, instead of hankies,” Irasga recalled.

Their preparations start as early as May. “We first discuss the problems encountered in the previous Traslacion then find ways to improve the next one,” Irasga told the Inquirer in an interview early this week.

Monthly meetings follow, until the last few days leading to the next procession call for ocular inspections of the route and dry-runs for maneuvering the carriage.

Quiapo Church parochial vicar Fr. Ric Valencia shared Irasga’s observation that the number of youth participants had been growing each year perhaps because traditions are passed on from parents to children.

But the downside is that “some of them are not following instructions anymore,” the priest said, noting that this rowdiness often resulted in injuries.

Organized laymen had been mounting the Quiapo procession as early as the Spanish colonial area, when the image was carried on their shoulders and devotees formed tempered lines on the street. Though a carriage is now used, present-day volunteers still refer to themselves as “mamamasan” (from the Filipino root word pasan, the act of carrying a load on one’s shoulders).

According to one of the elders, 65-year-old Boy Jongco, the group went by the name Gabay (guide) until the early 1980s before changing it to Hijos del Nazareno.

It is officially recognized by Quiapo Church and works under the supervision of the parish pastoral council. It currently counts around 8,000 members, not only in Metro Manila but also in Bulacan, Laguna and Pampanga provinces.

And yes, it has its own Facebook page (with about 10,000 “likes” as of Wednesday).

A Nazarene devotee aged 18 and above can apply for membership, but “we screen people first before accepting them because the task they need to carry out is not easy,” Irasga said. He should also have a “good moral standing” in the community and “complete sacramental documents (baptismal and confirmation certificates).”

A P100 membership fee is collected from each volunteer upon admission to cover the cost of his ID and Nazareno shirt, then P30 monthly for food and other expenses incurred in group meetings. Irasga said the parish had been very supportive, providing them shirts and meals on the day of the procession.

Their ranks cut across different sectors of the working class. “We have members who are police officers, seamen, vendors …,” said Irasga, a jeepney operator.

Outside the traslacion, “we also serve during Mass and participate in church activities,” he said.

For it is not only during the procession that the Black Nazarene’s army can show its faith and dedication, but also on ordinary days far from the madding, towel-throwing crowd, he stressed.

RELATED STORIES:

Nazarene devotees told to put contact numbers on children