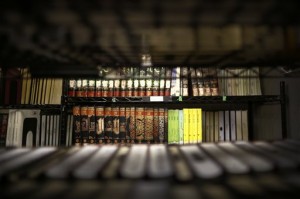

In this photo reviewed by the U.S. military, religious books, available for borrowing by detained al-Qaida and Taliban militants who were captured after the Sept. 11 attacks, are among 6,000 titles organized on shelves at Guantanamo Bay Naval Base, Cuba, Wednesday, Nov. 20, 2013. AP

GUANTANAMO BAY NAVAL BASE, Cuba—A persistent knock came from inside the heavy, locked cell door.

A young United States Army guard strode over and leaned in to hear the detainee through a shatterproof window.

“What do you want?” the guard asked, not unkindly, in one of the many daily moments in which suspected terrorists demand to be dealt with as their lives hang in legal limbo.

During nearly 12 years of legal disputes and political battles, the United States has put off deciding the fate of al-Qaida and Taliban militants who were captured after the September 11 attacks but denied quick or full access to the American justice system.

Now, as Congress considers whether to grant trials and transfers to most detainees, time may be running out on the law that allows the U.S. to hold them.

The 2001 law is known as the Authorization for the Use of Military Force, or AUMF. It allowed the U.S. military to invade Afghanistan to pursue, detain and punish extremists linked to the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001. The law has been used to justify attacks on militants in Pakistan, Yemen, Somalia and elsewhere.

Will it remain valid if U.S. combat troops withdraw from Afghanistan at the end of 2014—whether thousands stay as trainers or if the U.S. pulls out entirely? That’s an open legal question that, officials and experts say, must be resolved over the next year.

“The jury is still out on when the AUMF might expire,” said Army Lt. Col Todd Breasseale, a Pentagon spokesman. “Many argue that’s not set.”

If U.S. troops withdraw, “it certainly increases the pressure, as some administration officials have argued, to decide whether the AUMF should remain in effect as is, or if a new version is necessary,” Breasseale said in a statement.

In 2009, on the second day of his presidency, Obama ordered the terrorist detention center at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, to be closed within one year. Obama long has derided the facility, where critics say detainees have been abused, interrogated and held illegally, as a blow to American values and credibility worldwide.

Opponents in Congress refuse to let the detainees come to the U.S. for trial, citing security risks to Americans. Lawmakers have blocked the transfer and resettlement of most of the remaining detainees to other nations, fearing they will return to terrorist havens upon their release. Nearly 30 percent of Guantanamo detainees who have been released have since resumed the fight.

Today, 164 detainees are held at Guantanamo, down from a peak of about 660 a decade ago. Most were tried, transferred or cleared for release under President George W. Bush. Seventy-eight have left since Obama took office.

The sprawling camp of barbed wire and hardened cell blocks cost U.S. taxpayers about $454 million each year, that comes to about $2.7 million per detainee.

The facility shows no signs of shutting down beyond a temporary budget freeze on the detainees’ library, where well-worn copies of the Quran, the “Hunger Games” series and Obama’s book, “The Audacity of Hope,” are among the 6,000 titles available for reading.

New housing is being built for some of the estimated 5,500 U.S. troops and contractors at the Navy base. More than one-third of them work for the detention camp. Medical staff openly discuss how they will care for aging detainees in coming years.

The Republican-led U.S. House has written legislation that requires the Pentagon to give Congress an annual plan for Guantanamo until the youngest detainee, now in his late 20s, turns 66, meaning the detention camp could remain open for nearly 40 more years.

Early this year, as many as 100 detainees began a hunger strike to protest their uncertain fate. Guantanamo medical officials said last week that 13 detainees were so underweight that they must be force-fed if they refuse to eat, although some voluntarily accept food and nutrition drinks on any given day.

At least some detainees—Guantanamo officials won’t say how many—are treated regularly for mental health issues. Others lash out at camp personnel on a near-daily basis, biting and hitting medical staff and throwing feces and other bodily fluids at military guards. Many of those guards are in their 20s and suffering from post-traumatic stress from working 12-hour shifts with openly aggressive inmates.

During a brief observation this past week, several detainees appeared listless as they shuffled under dim lights to prepare for morning Islamic prayers. They looked of normal weight and in regular health, and wore beards and prayer caps. One approached a mirrored one-way window and stood wordlessly for several moments as if he knew people were watching him on the other side of the unbreakable glass. All the detainees are men.

The decision to close Guantanamo’s detention camp largely hinges on when the U.S. declares that the global fight against terrorism has come to an end.

Legal experts say the military cannot continue holding detainees if the fighting in a conflict during which they were captured is over. A 2004 Supreme Court ruling in a Guantanamo case warned of an “unraveling” understanding of long-standing laws of war if authorities creep beyond that widely accepted legal boundary.

The AUMF was designed to retaliate against those responsible for the 2001 attacks. But it has been stretched to permit lethal U.S. strikes against al-Qaida’s many allied affiliates, including extremists and guerrilla groups that have shown little or no interest in attacking American targets.

The Obama administration has appeared reluctant to scale back those authorities, which lets it conduct drone strikes on suspected terrorists in North Africa and the Mideast.

“Make no mistake, our nation is still threatened by terrorists,” Obama said last May in a speech in which he also repeated his demand that Congress allow trials and transfers for most Guantanamo detainees.

As it stands, the legal authority to hold detainees at Guantanamo will continue until either the president or Congress declares the fight over. Federal courts are gearing up to consider cases from Guantanamo detainees who, eyeing the looming end of the war in Afghanistan, will argue the law is no longer valid.

The chairman of the U.S. Senate Armed Services, Sen. Carl Levin, said it’s unlikely that either Congress or the White House will let the 2001 law expire. “As long as there is an al-Qaida that is threatening the U.S., no one is probably going to try that,” Levin, D-Mich., told The Associated Press.

Levin wants to allow some detainees to be transferred to other nations or trial in the U.S., and has included that in the 2014 Defense Department legislation that the Senate is considering after failing to approve it last week.

If any troops remain in Afghanistan even as trainers, as expected, then technically the U.S. still would be involved in active hostilities in Afghanistan, and “then at least arguably, the AUMF could still be in effect,” Levin said.

For the first time in years, senior administration officials held a closed hearing of a periodic review board this past week to start reconsidering the cases of 46 detainees who earlier were deemed too dangerous to release.

Most are from Yemen, where lawmakers say al-Qaida is too strong to risk releasing a detainee who might be easily re-recruited to jihad. But many never will be tried in a U.S. court because the government is unwilling to reveal its evidence in their cases, probably because it was obtained during harsh interrogations or though other classified methods.

Obama acknowledged in his May speech that it was unclear what will happen to those detainees if he were to close Guantanamo. But he expressed confidence “that this legacy problem can be resolved, consistent with our commitment to the rule of law.”

Six months later, administration officials say there’s been little progress so far, and U.S. Sen. Saxby Chambliss of Georgia, the top Republican on the Senate Intelligence Committee, said in a statement to the AP that those detainees are “among some of the most dangerous terrorists in the world. They belong at Guantanamo.”

He called Obama’s plan to close the detention facility “irresponsible.”

Pentagon lawyers have decided that an estimated 15 to 20 detainees can be tried in a military court. The cases of more than a dozen, including September 11 mastermind Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, are already being prosecuted.

An additional 84 detainees have been cleared for transfer, but are waiting for the U.S. to release them to nations that either will take them or are deemed secure enough by Congress to accept them. More than 50 of them are Yemeni.

William Lietzau, who retired from the Pentagon in August after more than three years as the deputy assistant defense secretary overseeing detainee policy, said the continued detentions puts the U.S. at risk of slipping into a perpetual state of quasi-war that has a dubious legal basis. He said the government needs to decide when it is no longer at war to keep it from relying on legal authorities that should be used only in cases of last resort.

“Guantanamo serves a useful purpose because it reminds us, ‘Hey, we’re still at war,'” Lietzau said in an interview. “We should not feel comfortable at war. We should seek to end that war as quickly as we possibly can. And criticism over drones and criticism over Guantanamo is what reminds us that war is hell.”

RELATED STORY:

Obama urged to fulfill Guantanamo closure pledge