2 types of crowds, same anguish at Naia, Villamor

ALL PACKED and ready to go, but all they got from the Philippine Air Force at Villamor on Wednesday was an apology. GRIG C. MONTEGRANDE

Looking in one direction was a woman anxiously lugging a box of groceries. Heading the other way was a man with his wife and child in tow, but who had lost 40 other members of his clan.

The first was just dying to get on a plane to finally see her homeless, starving family. The other had just disembarked from a C-130 after fleeing the same place where the first wanted to go.

Five days after Supertyphoon “Yolanda” devastated their home provinces, two types of crowds—melded by a tragedy whose full scale was yet to be known—packed Metro Manila airports, where officials struggled to find ways both to move urgently needed relief cargo and to manage the crushing human wave in and out of the calamity zones.

Wednesday’s heightened activity at Ninoy Aquino International Airport (Naia) and Villamor Air Base, both in Pasay City, also started revealing the magnitude of the international response to Philippine appeals for aid.

Among the arrivals were two batches of relief workers from Japan, a 15-member humanitarian reconnaissance team from the Canadian armed forces, two C-17 aircraft sent by Qatar air force, a 20-member Malaysian medical team, and similar delegations from Belgium and Estonia.

Article continues after this advertisementUsing smaller aircraft, airline companies also started sending chartered flights to hard-hit Tacloban City, where the airport could not yet accommodate bigger planes. Cebu Pacific said it would use only turbo-prop aircraft and prioritize humanitarian missions and passengers earlier affected by flight cancellations.

Article continues after this advertisementThe airline said it would retain its four daily flights to Tacloban as well as its three Cebu-Tacloban-Cebu flights.

The Civil Aviation Authority of the Philippines (CAAP) exempted flights that carry relief goods from paying airport and air navigation fees at Naia and Mactan-Cebu International Airport.

But underlying these logistical and aviation concerns were the fears and hopes of the thousands rushing to get to their stricken hometowns, and the thousands more who had managed to get out.

“There’s no communication with my parents and siblings. So rather than stay here and be worried, I decided to go there myself,” said Silvio Pontalba, who was in a queue for a flight to Cebu.

Pontalba, who comes from Isabel, a town west of Ormoc City, said he was planning to buy rice and supplies in Cebu before taking a ferry to Leyte.

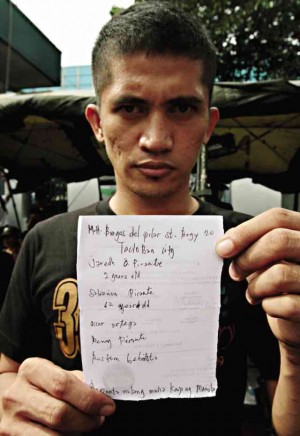

LOSING sleep over the uncertain fate of his loved ones in Tacloban City, Riyadhwine Pirante holds up a list containing their names as he desperately awaits a chance to take a plane home at Villamor Air Base in Pasay City on Wednesday. GRIG C. MONTEGRANDE

At Villamor, however, Philippine Air Force personnel turned away people who were hoping to hitch a ride on C-130 military planes. “We apologize that we can’t take them in. We hope they understand that our priority are the relief goods, medicine, medical and humanitarian personnel,” PAF spokesperson Lt. Col. Miguel Ernesto Okol told reporters.

“If I can’t go there personally, I want to make sure that they get these,” said Agnes Venancio of Novaliches, Quezon City, pointing to her box of canned goods.

But Jonas Mahilum, a 31-year-old cook from Las Piñas City, said he would not leave Villamor until he gets a plane to Tacloban, and burst into tears upon seeing a group of people arriving from his battered city.

“I have a wife and three children there. I want to know if they are still alive. If they are, I have food and medicines with me. Please help me go to Tacloban,” Mahilum told the Inquirer.

“I appeal to the Air Force generals. Please, I want to see my wife and five children,” said Rey Flores, another worried Leyte native.

With only P200 in his pocket, Flores still believed he could “find ways to help my family once in Tacloban. I’d lose my sanity if I remain here.”

Venancio and the others who have relief goods meant for relatives in Tacloban were referred instead to the nearby National Resource Operations Center of the social welfare department, where relief goods from the government and private donors were being packed.

On Tuesday night, a C-130 plane arrived from Cebu with refugees that included the family of Jaymar Lacandazo.

Lacandazo, who arrived with his wife and small child, recalled their traumatic encounter with Yolanda, whose rushing waters sent them climbing up to their ceiling, crawling out of it, and finally jumping onto a neighbor’s roof.

“People there did not really know what a storm surge was. I’m used to typhoons, but on that day the flood rose to more than a man’s height in less than a minute and began sweeping everything away,” he said.

Lacandazo said his clan lost about 40 members in the storm, and that he decided to go to Manila to seek help from other relatives.