Zamboanga coastal village gets top marine conservation area award

But the job is made more difficult by pirates, warlords and insurgents lurking in the surrounding conflict-ridden pockets of Mindanao, according to officials.

For meeting and rising above these challenges, the Tambunan Marine Protected Area in the small fishing town of Tabina was declared the most outstanding at the 4th Para El Mar Awards and Recognition held at the InterContinental Manila in Makati City on Aug. 15.

Para El Mar means “for the sea.”

The award seeks to recognize outstanding local efforts in conserving and sustainably managing coastal and marine resources, and serves as a learning opportunity for MPA managers to exchange and share best practices, organizers said.

The event was convened by the MPA Support Network and its partners the Department of Environment and Natural Resources, the UP Marine Science Institute, the Coral Triangle Support Partnership, the United States Agency for International Development, and the German Agency for International Cooperation.

Article continues after this advertisementThe Tambunan MPA received a cash prize of P100,000 during the awarding ceremony at the Intercon attended by almost 300 guests from government and non-government agencies, academic institutions and local partners.

Article continues after this advertisement“Considering that they have these realities that they’re facing every day, and still they made so much effort for conservation, I think that gives them an edge compared to the others,” one of the evaluators, marine scientist Dr. Hilly Ann Roa Quiaoit of Xavier University-Ateneo de Cagayan said of the Tambunan MPA.

“When they talk about piracy, it’s a reality they face every day,” she said in an interview.

Fishermen told the judges how they would need to give monthly dues to the so-called “mafia” of pirates in the area, she said. “Someone had just bought an engine boat, and it was taken by the pirates,” Quiaoit said.

Rey L. Sumagang, chief of Tabina’s municipal agriculture and fishery division that manages the Tambunan MPA, said the problem of “bad visitors” was not as bad as in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

But it is still there.

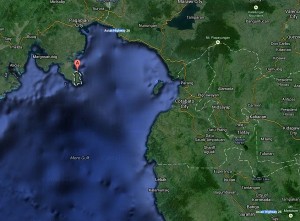

“If you will look at the Philippine map, Tabina is at the bottom. In front of it is Maguindanao …Then there is Cotabato, and then there is Basilan. That’s what we’re facing across the sea,” he said with a laugh.

“We know what sort of people are there. I can’t say the bad visitors all came from there but it’s hard to pinpoint,” he said.

But Sumagang said the community had taken measures to try to keep them away. “We talked to the mayor, and we talked to the extortionists. We gave them livelihood. We prioritized giving jobs to their spouses,” he said. “We don’t have as many bad visitors now unlike before.”

He said the secret to effective MPA management was a good working relationship with the local government.

“If you’re managing the MPA, the important thing you should have harmony with the mayor. You have to introduce improvements, innovation, so that by the time there is change of leadership, the people will have already accepted you. Then the mayor will also accept you,” he said.

The Tambunan MPA is both a mangrove area and marine sanctuary located in the village of Malim and extending 50 meters seaward from the shoreline.

The mangrove area spans 1,700 meters of coastline and an area of 103.5 hectares, while the marine sanctuary covers 1,000 meters of coastline and an area of 95 hectares.

The MPA is rich in mollusks, crustaceans like squid, octopus, cuttlefish, lobsters, blue crabs, shrimp and mangrove crabs. It is also frequented by abundant pelagic fish, such as mackerel, jacks, sardines, and sailfish, as well as coral and sand fish, including parrotfish, eels, siganids and goatfish.

Sumagang, a veterinarian, said absolutely no fishing and other human activity, excepting scientific research, was allowed inside the protected area. The only fishing takes place outside “buffer zones” some 100 meters away from the sanctuary.

“The good thing is the rural communities near the sanctuary have responded positively to what we do,” he said.

Quiaoit echoed his sentiment, saying, “They worked with the community, so they also had a perspective on the ground, and they’re quite aware of how important it is to preserve the area,” she said.

Another interesting “best practice” employed by the town is the strict adherence to ordinances that seek to connect conservation and local governance.

Sumagang said fisher folks who wanted to get their fishing vessels registered with the town government as mandated by regulations would have to show a “tree-planting certificate” duly signed by the district chair proving that they did plant 10 mangrove trees in one year.

“If you live 100 meters from the shoreline, you still have to plant 10 mangroves every year. If you apply for a marriage license, you would need to plant 10 mahogany trees. If you need to have an electric line connected, of course you’d need to get a permit from engineering, you’d need proof to show you actually planted 10 mahogany trees,” he said.

Quiaoit said the judges found the policy interesting and surprisingly effective.

“We even had to ask for evidence, and they were able to provide evidence. You see the consciousness of the whole LGU, such that the regular operations of the municipality, they try to connect it with conservation,” she said.

“It’s a good practice that LGUs can follow. It’s a good consciousness among the people, like, ‘what, I’m just going to get married, and I’d need to plant a tree?’” she said.

Sumagang’s proudest moment did not come from winning the Para El Mar, but something that happened on a recent Saturday.

“Our mayor had a civilian escort, and we were on standby at a cottage. The escort went to the sanctuary to check out the shells. He wasn’t going to take anything. He just wanted to look. Suddenly, a nine-year-old boy shouted ‘Sir, sir, you can’t go there. That’s our sanctuary’.”

“We almost dropped down to our knees,” he recalled. “Imagine that coming from a nine-year-old boy! It shows how [conservation] is in the consciousness of the people,” he said.

Even if my work is done, or I’m transferred, or I’m dead, I’m sure the next generations will preserve and sustain the MPA. That is the kind of acceptability I see from the community,” Sumagang said.