The Great Divide: The midterm election of 2013 (Part 2)

From the incarnation of our legislature in 1907 up to 1935, Filipinos had no say in the executive branch of government. After 1935, with a nationally elected chief executive with a single, six-year term, and a unicameral legislature with a three-year term, the midpoint of a president’s term coincided with the election of a new legislature, and thus, the midterm election was born.

In 1938, the first presidential midterms, the ruling Nacionalista Party, won an unprecedented (and still unsurpassed) 100% of the seats. This began a trend also unbroken to this day: no administration, ever, has ever lost either the National Assembly or the House of Representatives: even in years when the administration lost the presidency, the administration party won in the House—with membership shifting allegiances to the new administration. It also marked a unique opportunity for the presidency, during a time of strong party discipline: armed with such overwhelming success, it could command equally overwhelming support for any project requiring legislative support. That project was the amendment of the 1935 Constitution to restore the upper house and permit re-election for the president.

The result continues to have repercussions to this day, defining the dynamics of mid-term elections. For an extended period—1941 to 1969— House terms coincided with presidential terms, while only the Senate (or, to be precise, a third of it) was up for election midway through a president’s term of office. Both these trends combined to account for the reason why the midterm Senate results became, and continues to represent, a referendum on an incumbent chief executive.

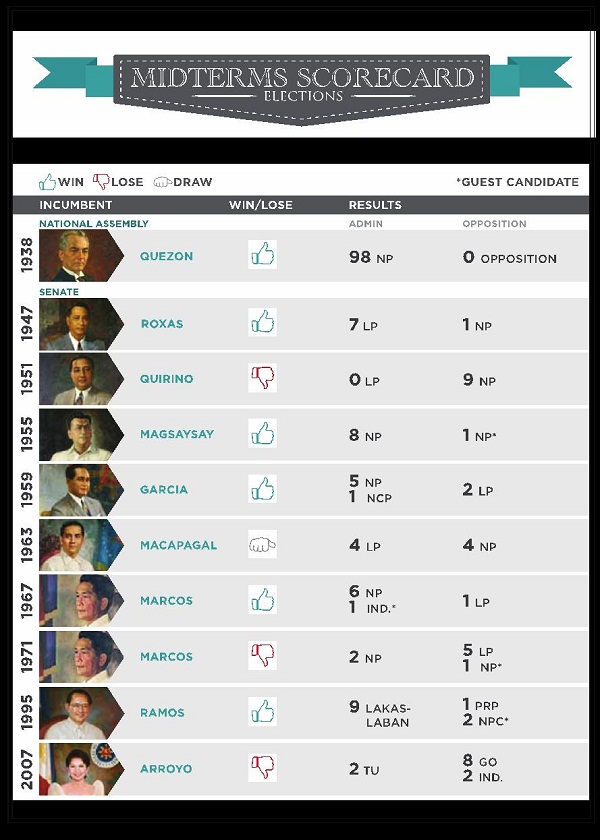

Consider the scorecard of administrations in the midterms:

From 1946 to 1971, the results determined whether a president’s ambition to succeed himself (when re-election to a second four-year term was still allowed) would be viable or not—meaning the Senate, too, served as a kind of proxy battle between the incumbent president and the opposition gearing up to challenge him in the next presidential polls. Our bicameral form of legislature, too, means that since 1941, the ability of a president to marshal the votes for his or her legislative agenda is dependent on whether there is an administration-friendly senate or not, since the iron-clad rule has been administration control of the House.

Article continues after this advertisementEven as observers point out that having a national mandate makes each senator essentially a republic unto his- or herself, making each senator and the Senate as a whole an effective counterfoil to presidents, it also means that administrations must mobilize to have an effect on the outcome of the Senate election. Senators who belong to an administration slate may be easier to talk to, all things considered, than those who campaigned as members of the opposition. In the head-counting that takes place leading up to each and every important vote, the slimness, or largeness, of the administration coalition can thwart or foster the legislative agenda of a president—not to mention the chances for confirmation of a president’s appointments, the prospects for the approval or rejection of treaties, or even the fate of investigations “in aid of legislation.”

Article continues after this advertisementAnd so: in the mad scramble for votes in a midterm election, if administrations can rely on the conventional wisdom that every House of Representatives is pliable, that administration’s efforts will involve a great deal of effort to determine whether a Senate will be cooperative or hostile. The opposition to any sitting administration will, conversely, campaign to demonstrate it is a viable administration-in-the-making, reinforcing the midterms-as-referendum dynamic.

Politics is addition

So where will the mad scramble take place? Considering time is limited, and resources, finite, the battle cannot be joined anywhere and everywhere.

In the old days, political strategists and observers referred to “the Solid North,” and—that uniquely Filipino term—“agruppations” such the Sugar Bloc, as well as local leaders reputed to be capable of mobilizing “command votes.”

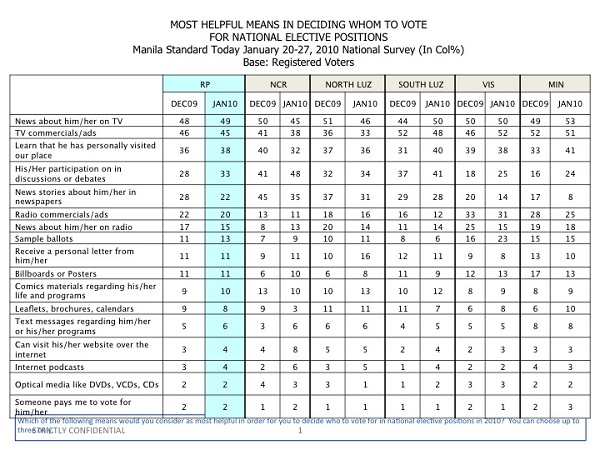

Table 1 shows that, as far as voters are concerned, media is supreme, and within media, television is king. The first two factors show this: the third, learning—not necessarily actually seeing firsthand, mind you—that a candidate has been to the voter’s area, also suggests an influential role for media in fostering this impression as a means to obtain votes.

And, as Rizal said, as the people are, so is their government: or to adopt the saying, as the people behave, so do the candidates make sure to focus their efforts to be noticed.

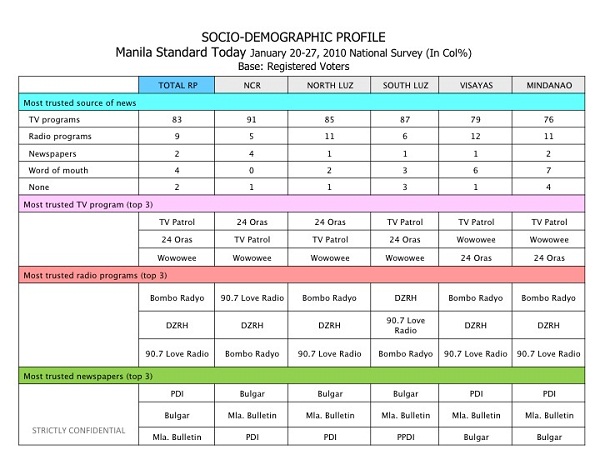

Table 2 provides a deeper insight into the “most helpful” means for voters to decide on who to vote for: “News about him/her on TV.” The following chart, also from the 2010 Manila Standard Survey, points to an extremely broad definition of what constitutes news, or, to be more precise, where people get “news”:

News programs, newspapers, and AM stations of national or regional scope with heavy news coverage aren’t surprising sources of news. But what is surprising to most people is that entertainment shows, FM radio, and tabloids are sources of “news.”

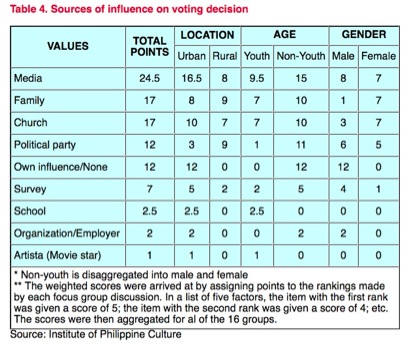

The last Table (4) is from much earlier, and comes from focus group discussions, a different methodology than the surveys above; based on a 2003 study by the Ateneo de Manila’s Institute of Philippine Culture, the findings provide insights into other factors not mentioned above.

It’s useful to factor in all of these things when considering the next part: where the votes are, and where the coalitions and candidates have gone a-courting for those votes.

A conventional campaign

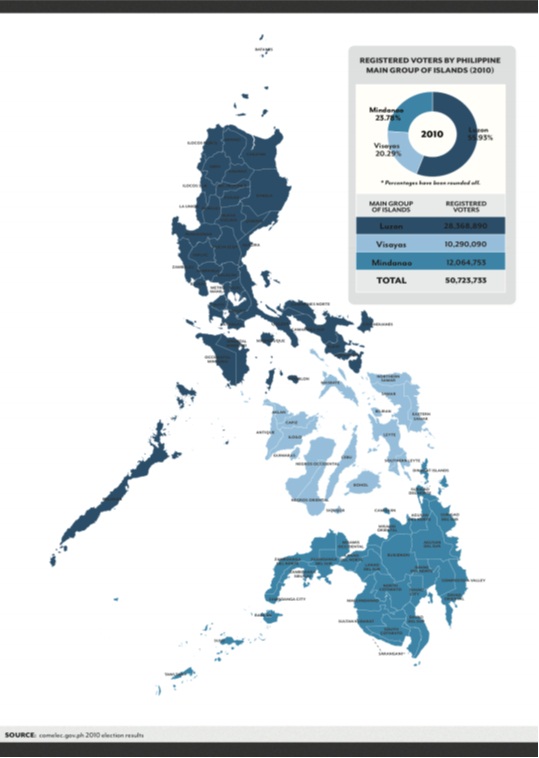

Take a look at Map 1, which shows where the votes are, as a percentage of the national whole. Luzon exceeds the Visayas and Mindanao combined.

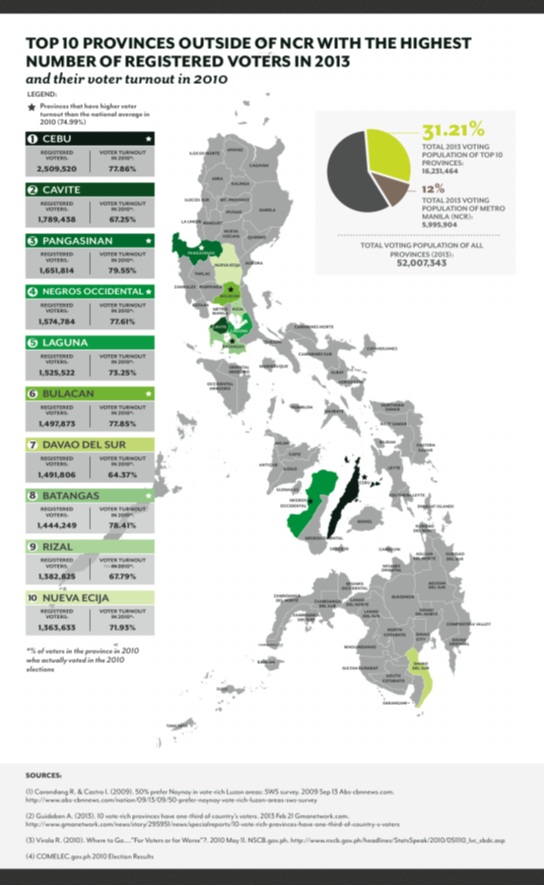

Now as for Map 2, it shows the top ten “vote-rich” provinces nationally, as well as the votes of Metro Manila, again, vis-à-vis the national whole. These areas not only have large voting populations: they have high percentages of voter turnout.

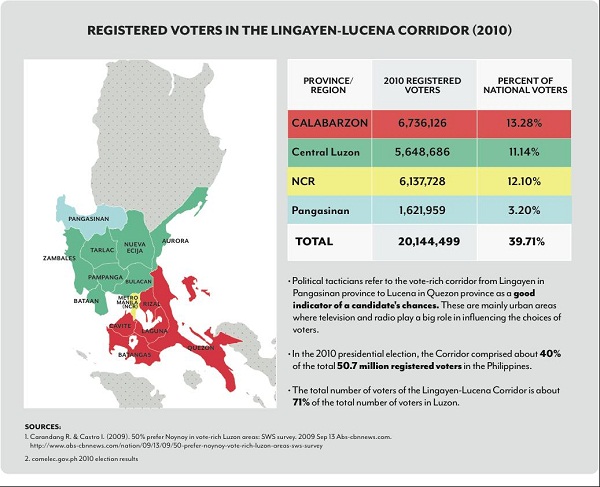

Now let’s zoom in, so to speak, on Map 3, which shows the Lingayen-Lucena “corridor,” with the respective percentage of the national vote each area within represents. These are areas, as the chart explains, which are often targeted for initial surveys when candidates and parties are considering their electoral chances; and which become a crucial battleground because residents are easily reachable by means of the media.

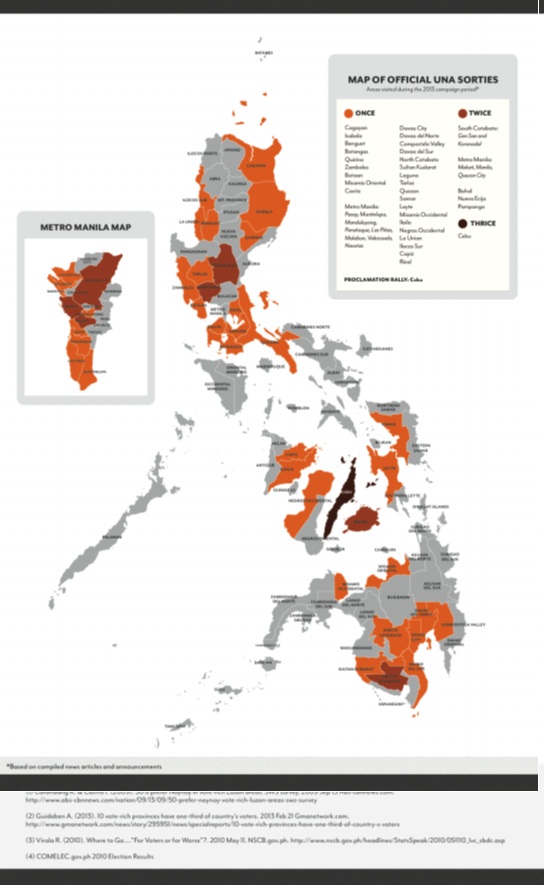

Take all of these maps together, and then refer to the next two maps, which illustrate the campaign sorties of the administration and the opposition. The first thing both maps tell you is that both sides ran a conventional campaign: they concentrated their time and efforts on places where the most votes could be found. The number of times specific areas were visited, also suggests that the two sides had mapped out where they felt opportunities and challenges existed; and finally, where they decided their time, efforts, and funds, would be best spent.

Map 4 shows where UNA held its sorties, as far as the national campaign is concerned. It suggests where the opposition believed fertile ground to exist; or where it believed it needed to take the fight or defend its advantages.

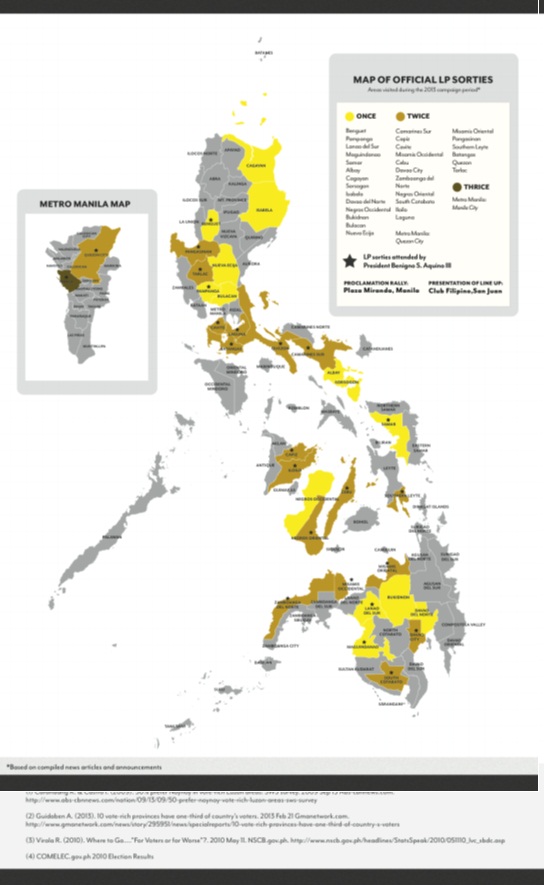

Map 5, on the other hand, shows the areas of concentration of the administration, with one additional factor that will probably be mulled over by the analysts once the results are in: namely, the places where the sorties were personally led by the President (suggesting the administration’s own perception of the strength of presidential endorsement, which will then be studied in terms of the outcome, to see the effects, if any and to what extent, of that endorsement).

What these maps point to, though, is the “ground war.” It will take media analysts, if they’re so inclined, to then compare this with the “air war”: were they complementary, or was the strategy somehow different?

At the start of the campaign, UNA, for example, was first out the gate with what it considered a fully formed slate; it proclaimed a tremendous advantage in terms of local alliances. But early on, it found itself unable to complete a full slate, preemptively dropping from its slate independent candidates who showed a preference for more closely adhering to the administration camp. Near the end of the campaign, however, it found itself conceding that local races would most likely go the way of the administration, while asserting that in 2016 a merry-go-round of party-switching would redefine the composition of contesting coalitions, anyway. Most of all, the administration-opposition dynamic asserted itself, much as perhaps there were those hoping to blur the lines between the two: and here, one significant factor was surely the President’s own categorical statement that his slate—named after himself—represented a referendum on his administration.

What all these things suggest, going into election day and whatever the eventual results, is this: for every political given, there is a fully explainable reason why that given is what it is. It exists because of changes in design (the consequences, intended, or otherwise, to the rules of the game as defined by the Constitution); changes in where voters are, and how they make their choices; and the history, in collective and individual terms, of everyone involved in the election: from the candidates, to the electorate, to the media and all those who are following the campaign and are trying to make sense of it all.

Further readings

This article continues a series I first began with “Elections are like water,” (2004) and “An abnormal return to normality” (2007) for PCIJ. Many of the details above came from my previous works, “Assembly of the Nation” (Studio5 Publishing, 2007), some blog entries, as well as the recent publication of The Philippine Electoral Almanac which can be freely downloaded online.

I would like to acknowledge the kind assistance of the following for the preparations of the charts and visuals for this article: Gino Bayot, David Manaois, Smile Indias, Cherie Tan, Joseph Casimiro, Angelica Misa, Ysa Lluisma, Maria Isabelle Itchon, Narilyn Joy Marquez, Karmela Mica Olaño, Nina Andrea Unlay.