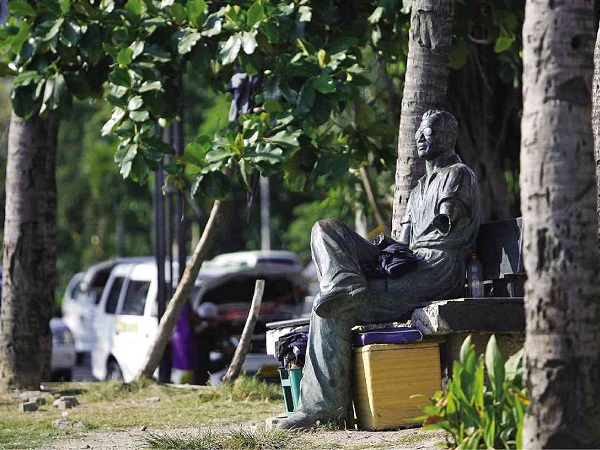

ARMLESS AND ABANDONED The Lacson statue has fallen into neglect after a storm knocked it out of place in 2011.

Bronze sculptures of illustrious personalities dot the windswept promenade facing Manila Bay along Roxas Boulevard in Manila. But after Typhoon “Pedring” battered the coastline in 2011, one statue has since lain in ruins, left at the mercy of vandals and vagrants.

The image is that of the man considered by many to be the best mayor the city ever had.

The statue of Arsenio “Arsenic” H. Lacson was removed from its place of prominence and consigned “to oblivion toward the US Embassy,” his daughter Millie Lacson-Lapira noted in a letter she sent to City Hall in July 2012.

Nine months later, Lapira’s request for the statue to be restored apparently remained unheeded. Worse, she and her family found more reasons to complain when they saw the spot on Sunday, a day before the 51st anniversary of Lacson’s death.

They found the space once occupied by her father’s image now taken over by another statue.

The Lacson sculpture—a work by Julie Lluch which captured him reading a newspaper on a park bench—was relocated to a spot nearer the US embassy, ironic for a media and political firebrand who was tagged “anti-American” during his day.

The seated figure had lost both arms. Gone, too, was the broadsheet Lacson was reading through his trademark aviator sunglasses. The bench that formed part of the sculpture was still there, but a homeless man had started using the space under it as his closet.

“We are appealing to your sense of propriety and history to give the proper recognition and respect for a man who served Manila so well,” Lapira said in her 2012 letter to the city government.

The Julie Lluch sculpture captured the power and confidence of Mayor “Arsenic” when installed years earlier on the walkway facing Manila Bay on Roxas Boulevard.

“It’s a travesty,” she told the Inquirer in an interview earlier this week.

Lapira recalled that hours before her family discovered the horrors on Roxas Boulevard, they visited Lacson’s tomb at Manila North Cemetery and found it also defiled by informal settlers.

Crops were being grown in what used to be a small garden adorning the tomb. Ducks were being raised in the two ponds next to it.

Other priorities

In an interview, Gemma Cruz-Araneta, deputy chair of the Manila Historical and Heritage Commission, explained that after the statues were swept off by Pedring, workers sent to restore them apparently had difficulty pinpointing their original locations.

“We’re also very concerned about this. But it may have been overlooked because of other priorities,” Araneta said

She said she had talked to sculptor Jonas Roces about restoring the image. (Lapira’s letter said Lluch, the original creator, had also expressed willingness to do the necessary repairs.)

Lacson served as Manila mayor for three consecutive terms from 1952 to 1962, leaving behind a deep imprint on the city that lasts to this day.

The mayoralty was an appointive position until 1951 and Lacson was the first to be elected to the post. Under his watch, the Quiapo underpass and the Manila Zoo were built. The underpass, an elementary school and a street in Sampaloc were later named in his honor.

He also laid down the concepts that later gave rise to the Pamantasan ng Lungsod ng Maynila and Ospital ng Maynila, projects completed by his successor Antonio “Yeba” Villegas after Lacson died of a heart attack while in office at the age of 49.

“Lacson did more for Manila than most of the mayors before him and after him combined,” Inquirer columnist Conrado de Quiros once wrote.

Before entering politics, Lacson was a journalist and radio man whose sharp-tongued commentary earned him the moniker Arsenic. At one point, then President Manuel Roxas, whom Lacson called “Manny the Weep,” suspended his show.

But this didn’t dim Lacson’s political star; before becoming mayor, he was elected congressman of Manila’s second district in 1949.

Lacson also railed against the presidency of Elpidio Quirino, who later suspended him when a judge sued him for libel. The Supreme Court voided the suspension order and Lacson was reelected mayor.

“Enemies at whom he sticks out his tongue perish completely from popular esteem, so fatal is the Lacson venom,” according to a 1957 Philippine Free Press article by Nick Joaquin.

Lacson kept his radio program

—prerecorded so that an editor could delete the expletives

—while running the city government. He joined the police in street patrols and, according to Joaquin, often took a jeepney to City Hall. “Nobody ever recognizes him without his dark glasses.”

He gave Philippine political punditry the phrase “so young yet so corrupt,” which he first uttered to describe a city councilor who is still very much around.

“It’s a Manila joke that the Tondo goons respect only two beings in this world—Mayor Lacson and the Señor Quiapo (image of the Black Nazerene),” Joaquin wrote.