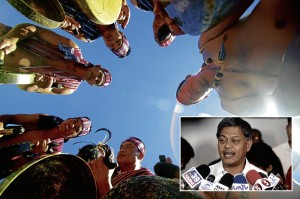

CIRCLE OF THE WISE Education Secretary Armin Luistro (inset) urges local governments to include indigenous knowledge and culture in the classroom subjects of grade school pupils, through ordinances, to pass down the wisdom of Cordillera elders to the next generation. RICHARD BALONGLONG

It’s not a confession one would expect from an education secretary.

Addressing a conference on indigenous education in Benguet last week, Education Secretary Armin Luistro said he belonged to a generation that was taught to believe that some indigenous groups, like those in the Cordillera, are uneducated, courtesy of a Western-oriented,

English-dominated curriculum.

“I come from an educational system that made me memorize from my grade school years the fact that the Philippines was discovered by [Ferdinand] Magellan on March 16, 1521 … and that Lapu-lapu is a nice fish,” Luistro said, adding that this was one of the many lessons that fostered prejudice.

“Little did I know that this singular memorized date had colored negatively my own view of the Philippines, my sense of self and how I have engaged the world even up to today,” he said at the conference organized to solicit ideas for the enforcement of Department of Education (DepEd) Order No. 62, the national indigenous peoples’ education policy framework.

“This is what education does. It teaches us a perspective. It teaches us how to think. But if we are not critical, education miseducates rather than brings us to another level of understanding, knowledge and wisdom,” he said.

Luistro said local governments could enact ordinances that would compel teachers to use indigenous knowledge and culture when they teach science, math and other subjects, in order to correct the miseducation suffered by his generation. According to DepEd records, 26,219 private elementary pupils and 215,480 public grade school pupils are enrolled for school year 2012-13 in the Cordillera.

The DepEd and other agencies should find a way of absorbing elders who know how to weave or build rice terraces as part of the official teaching staff, Luistro also said.

“It is our hope and dream our elders will be part of the education system. There is indigenous wisdom that will have to be transmitted [by elders] to students in our schools,” he said.

Luistro, however, said the bureaucracy only absorbs teachers who pass government licensure examinations.

“I don’t have the answers. We have to work this out. Do we need an equivalency [test] so a recognized elder can be absorbed [by DepEd] and knowledge is not lost?” he asked.

He said the reformed basic education program, popularly known as K+12 that is now being implemented, “is grounded on a conviction that indigenous peoples carry with them a wisdom that is largely misunderstood, maybe undocumented, and therefore unappreciated.”

“We are an educational system that has been a product—sometimes unwittingly—of a Western understanding of what we should know…. I was taught that [Cordillerans] were uneducated. That was ingrained in my memory for some reason or another. I don’t think it was in the textbook, but maybe that was the stereotype passed on to me,” Luistro said.

He said he assumed that the Ifugao rice terraces had no other name until he discovered the term “payew.”

A recent incident shattered all his prejudices. Luistro said: “I go to this rice paddy and I meet an old woman in Lagawe, [Ifugao]. It took me 30 minutes to cross a hundred meters [of a payew]…. Several meters away I saw a woman with a basket on her head and walking like Miss Universe gracefully on that ‘pilapil’ (paddy) and I thought to myself, ‘Uh-oh, what will happen, this is a one-way street.’”

He said he was ashamed when the woman stepped off the paddy but when he offered to also step away, she replied, in “impeccable” English, “That’s alright. I’m accustomed to this.”

“Do you realize what kind of mental framework that shattered in that one engagement? I realized that I have been miseducated by a system that perpetuates a cultural oppression and one that we have to change,” he said.

According to Luistro, it is now a DepEd policy to heed ordinances that compel the integration of indigenous information into classroom subjects.

“We cannot come out with a K+12 curriculum that is like a McDonald’s menu…. We can’t teach what an Ifugao knows to a Batanes pupil. It is not [about] uniformity, it is about standards,” he said.

He said educators won’t be starting from scratch.

In December last year, public school teachers in the Cordillera began designing courses that would teach students about climate science using the myths and folklore taught them by their elders.

The project was discussed at a Dec. 6 forum aimed at popularizing a DepEd mandate to include climate change and disaster risk management subjects in grade school.

Many schools in Benguet, which suffered from Typhoon “Pepeng” in 2009, have not integrated extreme weather changes in classroom discussions in part because of the trauma children have experienced from calamities, said Marivic Patawaran, officer-in-charge of the People’s Initiative for Learning and Community Development.

More than 100 people in Benguet died when Pepeng triggered landslides.