Class of 2012: Diploma dilemma for Europe graduates

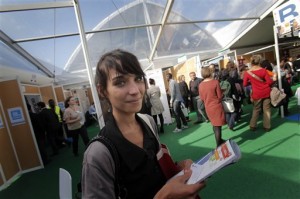

Estelle Borrell, 24, visits a job fair in Paris, Thursday, Oct. 4, 2012. Borrell studied law at Vienna University, where she dreamed of putting her passion into practice at an international organization. She got a shock when she began working at a Vienna law firm. AP PHOTO/CHRISTOPHE ENA

PARIS—Estelle Borrell knew she wanted to work in law since she was a teenager, when she interned at a court in Versailles, France. “The lawyers in their black robes, they were like gods to me,” said the 24-year-old Parisian.

Borrell studied law at Vienna University, where she dreamed of putting her passion into practice at an international organization. She got a shock when she began working at a Vienna law firm.

“I knew how to resolve cases on paper, but when I got into the law firm it was really ridiculous,” Borrell said. “My boss asked me to call a judge and I was absolutely not able to do it. I didn’t even have the vocabulary I needed to do a really simple call.”

Borrell, who is now back in France seeking work while continuing legal studies in Paris, had found out firsthand what educators, industry and governments across the continent are slowly coming to acknowledge as globalization intensifies competition and a devastating economic crisis swells youth unemployment: Europe’s universities, many founded during the Middle Ages, are failing to prepare students for the demands of the 21st century world.

Outmoded teaching

Article continues after this advertisementOutmoded teaching, overcrowded classrooms and even broken windows are common complaints by both teachers and students at French universities—even the Sorbonne, one of Europe’s oldest and most illustrious schools. Classes often begin with a hunt for spare chairs as classrooms built for 20 students regularly pack 40 or more. Sometimes students are forced to sit on tables or the floor. On Twitter, students post such complaints as: “Monday morning 9:00 in the constitutional law lecture at Paris 8, freezing my toes off, not very fun.”

Article continues after this advertisementRecently, a group of overwhelmed instructors at Paris University published an open letter to France’s education minister in daily newspaper Liberation to voice their frustration and call for the repeal of a reform that decentralized university control, which they blame for many of the universities’ woes.

In Spain, where universities are in even more dire financial straits, the heads of around 50 state-run universities recently made a joint statement warning of “irreparable deterioration” in education as crisis cutbacks choke academic institutions and threaten to hold back economic recovery.

Officials recognize the problem.

The European Commission, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development and the Federation of European Employers all have studies under way to examine why the continent’s universities are failing. The research aims to identify ways to better match universities’ output with the needs of employers, and hopefully help improve the job prospects of Europe’s graduates.

Weak showing

The failure of Europe’s universities is also reflected in their weak showing in the most closely watched barometer of university performance—Shanghai Jiaotong University’s annual ranking of the world’s universities, which places only two European universities, Oxford and Cambridge, in the top 20. The Shanghai Ranking focuses on research, looking at things such as the number of Nobel Prizes and citations in top academic journals, but experts see a correlation between a faculty’s academic caliber and quality of education.

And it’s precisely the failings of European university teaching that are now increasingly being put under the microscope.

A recent study in Britain showed that an increasingly large number of graduates are failing to find graduate-level jobs. The Futuretrack survey by Warwick University’s Institute for Employment Research showed that the number of graduates still without graduate-level jobs two years after leaving university nearly doubled to 40 percent last year compared to 10 years ago.

Much of the blame can be placed on Europe’s economic crisis, but experts say the problem also lies with the universities themselves, which are often accused of imparting theoretical abstraction with little practical application in the real world.

Some experts complain that students need to acquire a whole new way of thinking once they leave university.

“In social sciences, arts, IT, there is an enormous transition in which you almost have to tell people to forget what they’ve been studying so that they can see again,” said Robin Chater, secretary general of the Federation of European Employers.

Chater’s organization represents multinational firms working in the EU, advising them on employment law and other matters, and also functions as a think tank focused on issues of concern to international businesses. Students’ lack of practical experience in real-world situations is an emerging cause of concern for the organization’s membership, Chater said.

That’s an experience Lucy Nicholls, a member of AP’s Class of 2012, knows well.

“I’m not saying universities should find you a job, but they should mentally prepare you for the big wide world and make you very much aware of what the climate is like…,” said Nicholls, a 22-year-old fashion graduate in London. “It didn’t happen for me.”

Sorely disappointed

Nicholls describes herself as “sorely disappointed” by her university education in Britain. “I expected to have some sort of lecture on maybe how to go freelance, how to go into the world of fashion because freelance is such a big part of that industry,” Nicholls said.

The need to reform Europe’s universities has been identified by both the EU Commission and independent experts.

Although graduate unemployment at 5.4 percent is significantly lower than overall youth unemployment, university curricula “are often slow to respond to changing needs in the wider economy,” said Dennis Abbott, spokesman for the EU Education Commissioner. In an e-mail response to questions, Abbott said courses should be better tailored to the needs of the labor market, better guidance should be given in selecting courses, and students should be given more opportunities to develop entrepreneurial and work-relevant skills as part of their studies.

That’s precisely what Nicholls found lacking in her fashion studies. “I really just wasn’t given any opportunities,” she said. “I was very disappointed and I think the (university) could and should have done so much more.”

Disparity

Data from the EU Commission show the disparity that exists between the EU and the United States in terms of spending on university education, one factor that has been identified as a cause of European universities’ underperformance.

Total public and private spending on higher education in the European Union accounts for 1.3 percent of GDP, compared to 3.3 percent in the United States, according to EU figures cited in a 2008 report by the Brussels-based Bruegel think tank. On a per student basis, that translates to annual spending of euros 8,700 in the EU versus euros 36,500 in the US, Bruegel says.

Borrell, the French law student, saw the effects of this underfunding while in Vienna.

Her law school library shut as early as 4 p.m. some days, and was closed completely on weekends. “You can imagine what this means when exams are approaching and all of a sudden libraries are just literally stuffed with people,” Borrell said.

In its report, Breugel recommended that the EU spend an extra 1 percent of GDP annual on higher education, and give universities more autonomy in budgets, hiring and faculty pay as a way of giving the additional spending “more bite.”

Moira Koffi, another member of the Class of 2012, last month finished her diploma in corporate communications from the Sorbonne journalism school. Her experience provides an optimistic tale of what Europe’s universities may be doing right.

“I’m very satisfied” with how her school, CELSA, prepared her for finding post-graduation employment. “There were courses to prepare you for interviews, and networking was a very important” part of the curriculum, Koffi said.

In her case, it paid off: Koffi has just signed her first work contract with an important public relations firm, working on social media campaigns.—With Cassandra Vinograd in London