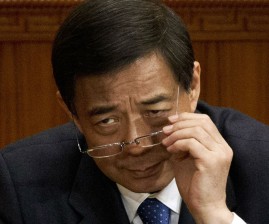

BEIJING— With China’s new leaders freshly installed in power, authorities are turning their attention to tying up loose ends in the sprawling, scandal-ridden city once ruled by populist politician Bo Xilai before his downfall buffeted the leadership transition.

In the past two weeks, authorities in Chongqing released a village official who had been sent to a labor camp for criticizing Bo. A lawyer disbarred after being convicted of having one of his clients lie in court has filed a petition for wrongful imprisonment. Meanwhile, a newspaper reported that hundreds of police officers who had been dismissed, demoted or otherwise punished were being quietly reinstated.

While the acts are being done piecemeal — the authoritarian government dislikes setting precedents — they show the leadership’s determination to quietly redress excesses of Bo’s four years in power in the southwestern metropolis.

Many in Chongqing are breathing easier too after Bo’s rocky reign, which won praise for an organized crime crackdown and promotion of communist culture and then widespread scorn as his career unraveled in seamy accusations of murder and corruption.

“I feel that this redress is necessary,” Wang Kang, an outspoken scholar in Chongqing, said in a phone interview. “This was a burden that was left in Chongqing. This burden must be removed so that Chongqing can breathe a sigh of relief.”

Chongqing, a breathtaking city of skyscrapers hugging steep hills along the Yangtze and Jialing rivers, has been portrayed as rife with cover-ups, power abuse and corruption under Bo and his police chief, Wang Lijun, in court documents. Since their removal, Bo’s wife has been sentenced to life imprisonment for murdering a British businessman and Wang given 15 years for corruption and covering up the murder. Bo awaits trial after the Communist Party purged him for obstruction of justice, corruption and sexual liaisons with numerous women.

The scandal exacerbated already divisive politicking for spots in the new Communist leadership, which culminated at a party congress last month. A new party secretary was chosen for Chongqing, a former agriculture minister known as a consensus-builder. In widely quoted remarks just days into his post, Sun Zhengcai said he was “resolutely opposed to the vulgar, extravagant, degenerate and depraved way of life.”

Bo brooked no dissent when in charge. He and Wang used the anti-gang crusade not only to go after organized crime but, according to victims, to cashier critics in the bureaucracy, jail rivals and pressure businessmen into steering deals toward Bo’s supporters. A campaign to sing revolutionary songs also intimidated critics, reminding many of the radical excesses of Mao Zedong’s rule when he was worshipped as a god.

“Wang Lijun was a law unto himself. If he didn’t like the way you looked he would arrest you on the spot,” Li Zhuang, the disbarred lawyer, said in remarks posted on the website of the state-run Global Times.

Li, a defense attorney known for his toughness, was jailed for 1 ½ years after his mafia boss client claimed Li told him to say police tortured him. Li’s prosecution marked a turning point when many educated Chinese began to suspect that Bo’s anti-mafia efforts had gone too far.

Li submitted a petition to Chongqing court authorities demanding a thorough investigation of his case. Last week, officials from the court and city prosecutor’s office met with him for informal discussions about his petition, Li said in a phone interview.

Ren Jianyu, an official in a village on Chongqing’s outskirts, criticized the Maoist revival campaign on the Internet and then was sentenced without trial to two years in a labor camp. Among the 1,000 other inmates in the labor camp were about a half-dozen like him, in for political crimes.

But then late last month, 15 months into his sentence, Ren was released; no reason given.

“Now that we are no longer living under such a state of high pressure, for us who have been attacked and persecuted, things are comparatively better,” Ren said. He has filed an appeal against his sentence to clear his name.

Meanwhile, the Southern Weekend newspaper reported that police in Chongqing were quietly rehabilitating and making restitution to around 900 police officers in Chongqing who had been fired, demoted or otherwise unjustly treated. Li, the former attorney, said Wang wanted to make sure only officers he could trust remained in the force and so purged anyone suspect.

A Chongqing police spokesman who would only give his surname, Deng, said police have been handling such appeals on the basis of “seeking truth from facts.”

“Mistakes must be corrected,” said Deng, who refused to provide any other details and repeatedly hung up when further questions were asked.

How far authorities will go to redress the wrongs of the Bo period remain to be seen. In the past, the government has been reluctant to offer wholesale amnesties. Although the crime of counter-revolution was dropped from the criminal code in the ’90s, those serving time did not receive a blanket release.

Ren, the former village official, said he would only believe real change had come if his appeal against his sentence was successful.