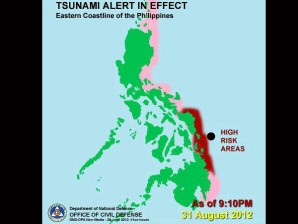

Coastal areas of the Philippines where tsunami warning is up. Issued by the Office of Civil Defense as of 9:10 p.m. Friday.

Families returned to their quake-devastated homes in Eastern Samar Sunday, ignoring government warnings to relocate away from danger zones.

A politician saw the stream of people going back to their villages as a return to normality, and said it was a good time for local governments to step up efforts to relocate families living in the many danger zones in the province.

“We still need to enhance [safety precautions]. There are many places here [that have been] declared hazard areas, but the people have not relocated,” said Eastern Samar Representative Ben Evardone.

He knew why, and so did the local governments.

“We have nowhere else to go, that is why we are trying to rebuild here,” Agence France-Presse quoted Rosel Aruera, 20, a resident of General MacArthur town, as saying to explain why she and her family returned after Friday night’s 7.6-magnitude earthquake destroyed their home.

Near where her family’s house used to be in the quiet fishing town, men, women and children picked through the debris, looking for materials to salvage from their splintered wooden houses.

The town faces the Pacific Ocean on the country’s eastern seaboard, where the powerful earthquake struck, triggering a tsunami alert that forced more than 200,000 people in coastal towns up to eastern Mindanao to flee.

“We thank the Lord that no big waves came, but still, the earthquake destroyed our home,” Aruera said.

“It was so strong we were thrown off our bed and minutes later our floor and walls crumbled,” she said.

Hers was among 80 seaside homes built on stilts using cement and wood, common structures in many coastal areas across the country.

Repeated warnings

Amador Evallo, a barangay (village) captain in General MacArthur, said the local government had repeatedly warned people to relocate to safer areas inland.

“All of their houses have been destroyed, and now they are trying to rebuild on the same spot,” he said. “But what happens when another earthquake or tsunami comes? That would be nightmare.”

The quake spurred tsunami warnings from as far away as Japan, Indonesia and Papua New Guinea. But only waves of up to half a meter hit parts of the Philippines’ eastern coast, not high enough to cause any damage.

The National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council (NDRRMC) in Manila said most of the homes destroyed were those made of light materials, while overall damage to infrastructure remained minimal.

But NDRRMC chief Benito Ramos said the quake served as another reminder for many local governments to improve disaster preparedness and relocate entire villages away from danger zones.

“We are lucky this time. But we can’t count on luck all the time,” he said. “We also understand that politically it is easier to say they will relocate communities, but it is more difficult to implement.”

Biggest challenge

“That’s the biggest challenge, how to convince them to relocate to safer areas,” Evardone told the Philippine Daily Inquirer in a phone interview.

One solution, he said, is for local governments to build schools, health centers and other public facilities in places far from hazard areas.

Since people frequently use public facilities, they would be enticed to move near such facilities, away from danger zones, he said.

Damage

Evardone, a former governor of the province, spoke about one local official whom he did not name but praised for showing political will and relocating an entire community. The official, he said, bought a piece of land near schools and other public facilities and moved the community there.

The Office of Civil Defense said the earthquake, which struck 112 kilometers east of Guiuan, in the Philippine Trench, caused more than P11.8 million in damage to public and private infrastructure in the province.

Damaged were the Layug bridge in Barangay Casoroy, San Julian, which was impassable; the Buyayawon bridge in Mercedes; and the San Eduardo bridge in Oras. Cracks were also found on the highway in Del Remedio, Sulat town.

The damage to Sulat bridge is estimated at P3 million; to Layug bridge, P4 million; and to Buyayawon bridge, P3 million.

The earthquake also damaged the Wright-Taft-Borongan Road, which would cost P1 million to repair; the junction of the Buenavista-Lawaan Road, P500,000; and the junction of the Taft-Oras-San Policarpio-Arteche Road, P300,000.

Evardone said President Benigno Aquino and the Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH) had assured him that the roads and bridges in the province that the quake had damage would be repaired immediately.

Aftershocks

Not all who fled their homes when the tsunami alert was raised were going back. Ramos said 300 families remained in various evacuation centers in two towns in Eastern Samar.

“Those who remained in evacuation centers feared for their safety, as more than 200 aftershocks had been reported since Friday night,” Ramos said.

The Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology (Phivolcs) has recorded 271 aftershocks in the Visayas and Mindanao since the quake struck at 8:47 p.m. Friday.

Phivolcs Director Renato Solidum said the aftershocks may last for several weeks or months after the main seismic event.

“The initial aftershocks are expected to be strong but will lessen in magnitude and frequency after some time,” Solidum said.

Ramos said the remaining evacuees were housed in public schools, gymnasiums and cockpit arenas in the towns of Guiuan and Mercedes.

“Some of the evacuees even chose to stay on top of trees,” he said. “They immediately went to high grounds even before we issued Alert Level 3,” he added.

The Philippines is one of the most disaster prone countries in the world, with an average of 20 typhoons battering the island nation every year.

It also sits on the Pacific Rim of Fire—a belt around the Pacific Ocean dotted by active volcanoes and unstable ocean trenches.

Heavily populated urban areas on the Philippines’ main island, Luzon, including the capital Manila, sit on or are near at least four fault systems.

Most active fault

The most active of these, the Valley Fault System, cuts through the eastern section of Luzon, including across Manila and suburban areas to the south.

That fault moves once every 200 years to 400 years, the last time in the 17th century, seismologists said.

Ramos said a 2004 study jointly carried out with Japan said a movement of the Valley Fault System could trigger a 7.2-magnitude quake, flattening 40 percent of all buildings in Metro Manila, which has a population of 15 million.

Tens of thousands would also die, he said.

“Friday’s earthquake off the coast is reminding us that these faults could move any time,” Ramos said. With reports from Jeannette I. Andrade in Manila; Joey A. Gabieta, Inquirer Visayas; and AFP