Gov’t studies giant cistern at Taguig’s Global City for Metro flood control

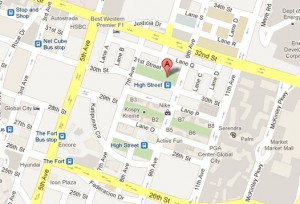

MANILA, Philippines—Did you know that Burgos Circle at the Global City in Taguig has a five-story structure underneath it where floodwater is impounded and later released into Manila Bay?

MANILA, Philippines—Did you know that Burgos Circle at the Global City in Taguig has a five-story structure underneath it where floodwater is impounded and later released into Manila Bay?

The government is now looking at it, or the principle behind it, as a model for the construction of a similar structure that would impound water up in the Marikina Watershed, the main source of the floodwaters that swamped Marikina and its neighboring cities in last Tuesday’s deluge.

“What we’re looking at is to impound or retard the amount of water together with the run-off upstream. It’s been effective in many countries and we’ve tried that in Fort Bonifacio,” Public Works Secretary Rogelio Singson said in a brief phone interview Saturday.

At the Burgos Circle’s water impounding facility, which Singson helped design when he was still in the private sector, floodwater is stored, and after the rains, is pumped out to creeks that flow into the bay, the public works secretary said.

In his swing through flooded areas in Metro Manila last Thursday, President Benigno Aquino said catch basins in the Marikina watershed, a ring-road dike along Laguna de Bay, and a dike and pumping station in Camanava area would be built in two to three years to address perennial flooding in the metropolis.

For several years, runoff from the 26,000-hectare denuded watershed has been a major cause of flooding downstream, including Antipolo City, Montalban, San Mateo and Tanay towns, all in Rizal province, and Marikina.

Article continues after this advertisementAs in the onslaught of Storm Ondoy in September 2009, rainwater came tumbling down from the watershed that swelled Marikina River and swamped subdivisions along the river and parts of Rizal in last week’s massive flooding caused by days of monsoon rains.

Article continues after this advertisementOn Friday night, the river swelled anew after hours of thunderstorms, triggering panic and prompting evacuations of residents who had gone back home.

“All of the rainwater goes down to us. We suffer a lot from the floods, and 98 percent of that comes from the watershed. And there’s not a single foot in the watershed that belongs to Marikina,’’ Marikina Rep. Federico Romero Quimbo said by phone.

Quimbo said the water impounding project was now on the drawing boards of the Department of Public Works and Highways, and this could take the form of either a dam, or a diversion tunnel.

But unlike Burgos Circle’s facility, Singson said, the proposed project in the Marikina watershed would have a dual role: impound water to protect the residents downstream, and provide the capital another source of potable water.

“We’ll use storm water for domestic use,” Singson said.

That was the idea, said Quimbo, who was optimistic the “pipe dream” would become a reality during the Aquino administration.

“That has always been a pipe dream; an empty promise in the past. But now we’re strongly convinced it will become a reality. The President will not say anything unless he means it. And Secretary Singson has the competence to do it,” the lawmaker said.

Since public works officials have yet to present the detailed plans, Budget Secretary Florencio Abad could not give the exact cost of the project, except to say “this will be in the billions of pesos.’’

“The immediate and short-term requirements may be drawn from budgetary allocations, but the medium and long-term funding will have to be drawn, in addition, from ODA (official development assistance) and PPP (public-private partnership) funding,’’ he said.

PPP funds are often allotted for “self-liquidating projects” like water supply, hydro power, solid waste management and sewage services, he said.

Abad agreed entirely with the principle behind the project.

“We cannot mitigate the flooding unless we can significantly contain the runoff of rainwater, especially that cascading from the mountains and released from dams,’’ he said.

The good thing is that the government could look at this situation and “see how we may harness it to benefit, instead of, harm” people, he said.

“How can we now use the excess water for irrigation, aquaculture, potable water supply, reforestation and even for hydro power?” he said.