While an animal rights watchdog contends that Manila zoo’s lone elephant is suffering physically and psychologically, her “best friend” has come out to air sentiments to the contrary.

The first has managed to internationalize the issue by gaining expressions of support from British rock star Morrisey, American pachyderm expert Henry Richardson, and, just last week, Nobel Prize-winning novelist J.M. Coetzee.

The other owns the hand that has patiently fed and pampered “Mali” for more than a decade.

Mali may be alone but not unloved, according to veteran advertising photographer John Chua, who has served as the animal’s volunteer caretaker since 2001.

Chua is almost single-handedly challenging the views of the group People’s Ethical Treatment of Animals (Peta) concerning its campaign to have Mali transferred to a nature sanctuary in northern Thailand.

“Don’t tell me she’s sick or that she’ll die if she’s not moved. I’ve taken care of her for 10 years. That’s no joke,” Chua said in a recent interview, when he spent yet another morning at the zoo to feed and play with Mali.

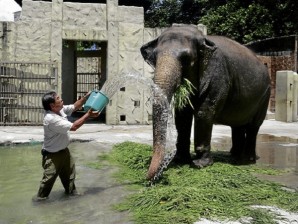

Chua has become known to zoo visitors and administrators as Mali’s pro bono keeper, often the only person capable of approaching Mali without any difficulty. He treats her almost every day to her favorite food like mangoes, bananas, even orange-flavored popsicles.

He gives her a shower and a soothing spray on her massive feet, and puts her through what he called an “enrichment program” that includes “coconut football” or a lazy dip in a puddle.

But for someone who shares the same objective as Mali’s avowed protectors, Chua is not exactly on the same page as Peta. “I really have no problems with having her transferred … but I’m questioning [Peta’s] sincerity,” he said quite bluntly.

“What is Peta’s objective? Why are they doing this? To raise funds? If that is so, then just leave us alone. If they really care for her, care for her now. Because I do,” he said.

(Chua’s advocacy also includes encouraging parents of children with autism to let the kids explore the world through photography. He has also organized field trips to the zoo for visually impaired children to encourage them to conquer their fears and discover new thrills by touching some of the animals, including Mali.)

He started attending to Mali in support of his daughter’s stint as a zoo volunteer in 2001. He has since donated a water pump for Mali’s enclosure, found private sponsors for other improvements at the site, and even trained how to handle such an animal in Singapore and at the Pinnawala elephant orphanage in Sri Lanka where Mali came from—all to “make her life better.”

It was therefore no surprise that when local Peta members brought Richardson to the country in May, Chua, along with the zoo veterinarians, was there to show them Mali.

Richardson, a California-based elephant specialist for 40 years, later released a report on Mali’s condition, which he said was based on his visual inspection of the 38-year-old behemoth.

“My major concern is that Mali is alone,” Richardson said in his report, which Peta cited in a campaign statement. “Mali’s social and psychological needs are being neglected at Manila Zoo. Even the best intentions of … her keepers, who all clearly care about her well-being, cannot replace these needs, which can only be met by the companionship of other elephants.”

Chief zoo veterinarian Donald Manalastas said the zoo administration had agreed to train Mali to be more cooperative during foot care procedures, as suggested by Richardson. He said they were also heeding the veterinarian’s advice that they add more soil and greenery in the enclosure.

But for Manalastas, Mali, who arrived in the zoo in 1980 when she was only three years old, cannot survive in the wild because she was bred in captivity.

Chua agreed that something needed to be done about Mali being alone. He challenged Peta, however, to come up with a solid plan for her transfer and long-term care in a sanctuary. In the meantime, he said, they must help make her living conditions at the zoo better.

Chua noted that Peta’s protests against Mali’s stay in the zoo seem to be a recurring theme every year. “Last year they made a call for donations for Mali on their website,” he recalled.

But for Peta-Asia campaigns manager Rochelle Regodon, “the obvious problem with the zoo is that Mali is alone. Her mental suffering cannot be understated.”

“The simple fact is that Mali will have a much better life in a sanctuary,” she said, adding that a sanctuary in northern Thailand, which was highly recommended by experts, had agreed to accept Mali.

Peta will shoulder all expenses for Mali’s transfer, including her preparation for travel, Regodon said. “The sanctuary currently houses 14 other elephants who were formerly captive or working elephants, and the staff feels that Mali will be able to integrate with them quickly.”

“The only one making money off Mali is the zoo, but it has completely failed to care for her. It’s time to put politics and ego aside and do the right thing. Moving Mali to a sanctuary would give every Filipino something to be proud of, in that we would be showing our Asian neighbors and the world that Filipinos are kind to animals and that we are a compassionate, progressive nation,” she said.