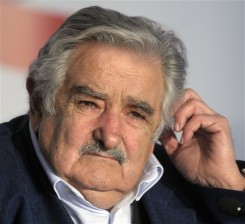

Uruguay's President Jose Mujica's government plans to take a step beyond legalizing marijuana. It wants to sell it. Local news media and lawmakers report that the government plans to send a bill to Congress on Wednesday that would legalize marijuana sales as a crime-fighting measure. Only the government would be allowed to sell the marijuana cigarettes, and only to adults registered as users. (AP Photo/Matilde Campodonico, File)

MONTEVIDEO, Uruguay — Peaceful Uruguay is planning a novel approach to fighting its rising crime: having its government sell marijuana to take drug profits out of the hands of dealers.

Under the plan backed by President Jose Mujica’s leftist administration, only the government would be allowed to sell marijuana and only to adults who register on a government database, letting officials keep track of their purchases over time. Profits would reportedly go toward rehabilitating drug addicts.

“It’s a fight on both fronts: against consumption and drug trafficking. We think the prohibition of some drugs is creating more problems to society than the drug itself,” Defense Minister Eleuterio Fernandez Huidobro told reporters late Wednesday.

Fernandez said the bill would soon be sent to Congress, which is dominated by Mujica’s party, but that an exact date had not been set. If approved, Uruguay’s national government would be the first in the world to directly sell marijuana to its citizens. Some local governments do so.

The proposed measure elicited responses ranging from support to criticism to humor.

“People who consume are not going to buy it from the state,” said Natalia Pereira, 28, adding that she smokes marijuana occasionally. “There is going to be mistrust buying it from a place where you have to register and they can typecast you.”

Media reports have said that people who use more than a limited number of marijuana cigarettes would have to undergo drug rehabilitation.

“I can now imagine you going down to the kiosk to buy bread, milk and a little box of marijuana!” one person in Uruguay’s capital, Montevideo, wrote on their Twitter account.

Behind the move is a series of recent gang shootouts and rising cocaine seizures have raised security concerns in one of Latin America’s safest countries and taken a toll on Mujiica’s already dipping popularity. The Interior Ministry says from January to May, the number of homicides jumped to 133 from 76 in the same period last year.

The crime figures are small compared to its neighbors Argentina and Brazil but huge for this tiny South American country where many still take pride in its safety leaving their doors open and gathering in the streets late at night to sip on traditional mate tea.

To combat rising criminality, the government also announced a series of measures that include compensation for victims of violent crime and longer jail terms for traffickers of crack-like drugs.

The idea behind the marijuana proposal is to weaken crime by removing profits from drug dealers and diverting users from harder drugs, according to government officials.

“The main argument for this is to keep addicts from dealing and reaching substances” like base paste, a crack cocaine-like drug smoked in South America , said Juan Carlos Redin a psychologist who works with drug addicts in Montevideo.

Redin said that Uruguayans should be allowed to grow their own marijuana because the government would run into trouble if it tries to sell it. The big question he said will be, “Who will provide the government (with marijuana)?”

During the press conference, the defense minister said Uruguayan farmers would plant the marijuana but said more details would come soon.

“The laws of the market will rule here: whoever sells the best and the cheapest will end with drug trafficking,” Fernandez said. “We’ll have to regulate farm production so there’s no contraband and regulate distribution … we must make sure we don’t affect neighboring countries or be accused of being an international drug production center.”

There are no laws against marijuana use in Uruguay. Possession of marijuana for personal use has never been criminalized here and a 1974 law gives judges discretion to determine if the amount of marijuana found on a suspect is for legal personal use or for illegal dealing.

Liberal think tanks and drug liberalization activists hailed the planned measure.

“If they actually sell it themselves, and you have to go to the Uruguay government store to buy marijuana, then that would be a precedent for sure, but not so different than from the dispensaries in half the United States,” said Allen St. Pierre, executive director of U.S.-based National Organization for the Reform.

St. Pierre said the move would make Uruguay the only national government in the world selling marijuana. Numerous dispensaries on the local level in the U.S. are allowed to sell marijuana for medical use.

Some drug rehabilitation experts disagreed with the planned bill altogether. Guillermo Castro, head of psychiatry at the Hospital Britanico in Montevideo says marijuana is a gateway to stronger drugs.

“In the long-run, marijuana is still poison,” Castro said adding that marijuana contains 17 times more carcinogens than those in tobacco and that its use is linked to higher rates of depression and suicide.

“If it’s going to be openly legalized, something that is now in the hands of politics, it’s important that they explain to people what it is and what it produces,” he said.

Overburdened by clogged prisons, some Latin American countries have relaxed penalties for drug possession and personal use and distanced themselves from the tough stance pushed by the United States four decades ago when the Richard Nixon administration declared the war on drugs.

“There’s a real human drama where people get swept up in draconian drug laws intended to put major drug traffickers behind bars, but because the way they are implemented in Latin America, they end up putting many marijuana consumers behind bars,” said Coletta Youngers, a senior fellow at the Washington Office on Latin America think tank.

“There’s a growing recognition in the region that marijuana needs to be treated differently than other drugs, because it’s a clear case that the drug laws have a greater negative impact than the use of the drug itself,” Youngers said. “If Uruguay moved in this direction they would be challenging the international drug control system.”