PH a middle class country? Target still elusive

(First of two parts)

MANILA, Philippines—Philippine officials have set an ambitious target to turn the country into a predominantly middle society by 2040, where poverty is a thing of the past.

The vision, which originated from the National Economic Development Authority (Neda)-initiated “AmBisyon Natin 2040” project that began in 2015, aims to ensure that all Filipinos lead a secure, comfortable, and flourishing life.

The goal is to eradicate hunger and poverty, provide equal opportunities for everyone, and establish fair and inclusive governance.

READ: Harmonizing AmBisyon Natin 2040 and Dream Philippines 2040

The goal, however, faces significant challenges, particularly with global economic headwinds and the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS) senior research fellows, Dr. Jose Ramon G. Albert, Dr. Roehlano Briones, and Dr. John Paolo Rivera, authored a discussion paper titled “Wealth Creation for Expanding the Middle Class in the Philippines.”

The paper argues that achieving the vision of a predominantly middle-class society will require bold and coordinated action in several priority areas.

The background paper stated that growing the middle class is more about fostering new wealth creation rather than merely focusing on poverty reduction or wealth redistribution.

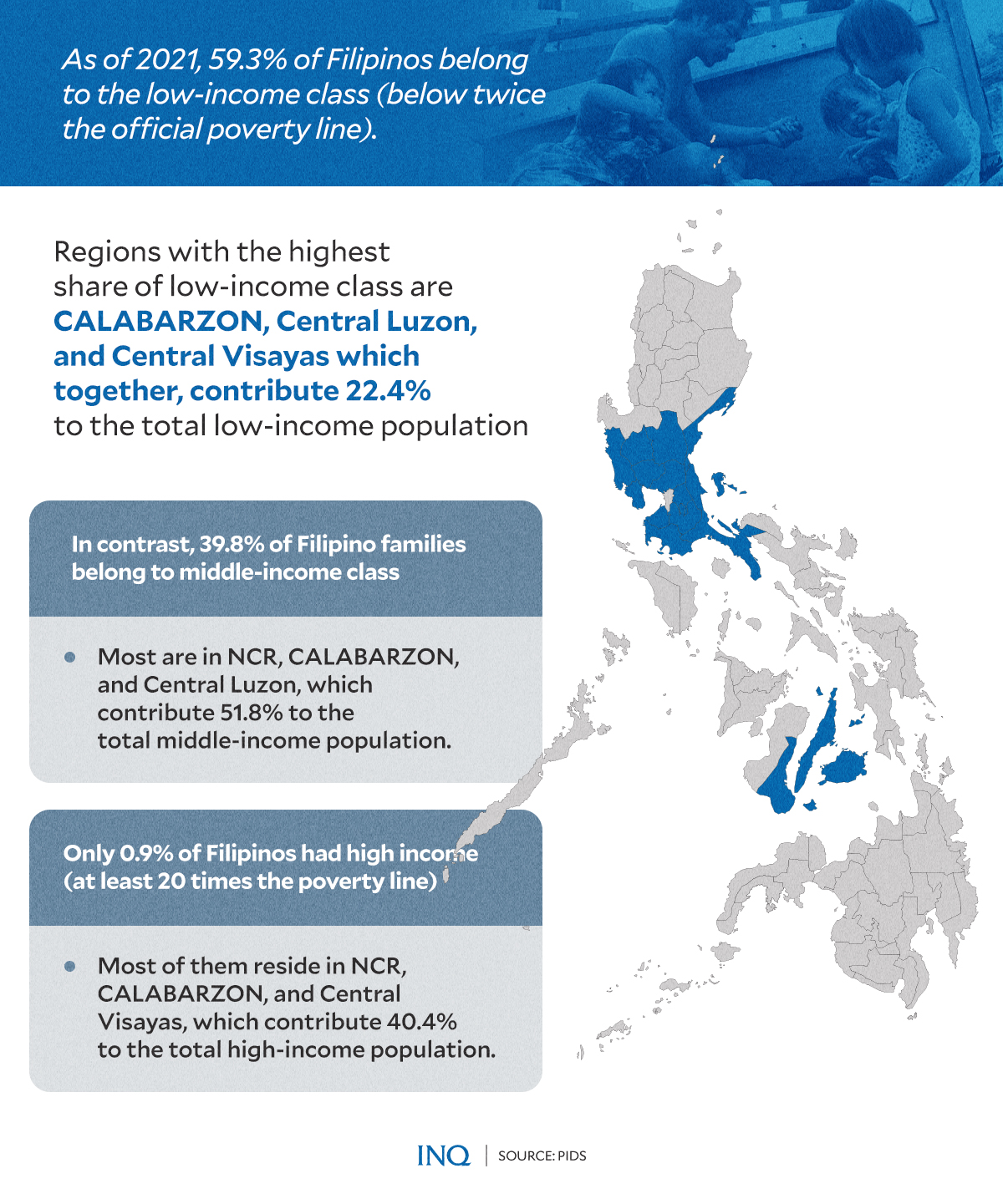

It also noted how the middle-class population has grown in the past years. However, this growth has been uneven, with the COVID-19 pandemic reversing some of the gains made in recent years.

“The question is, how can we grow the middle class to be around, let’s say, 80 percent in the next few years?” Albert asked in his presentation at the launch of the 22nd Development Policy Research Month (DPRM) of the PIDS.

Growing middle-class population

The middle class is vital for the country’s economic growth, social stability, and sustainable development.

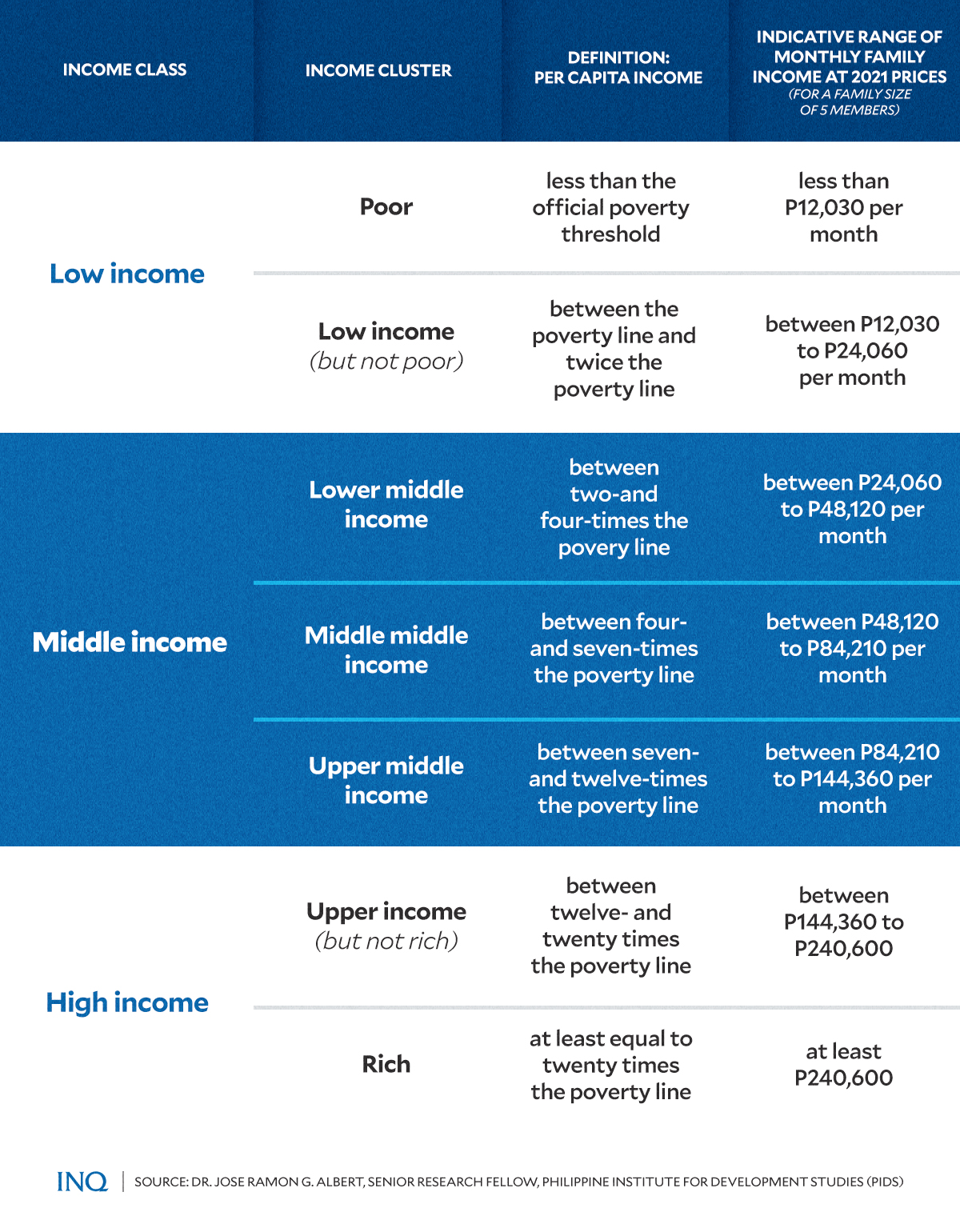

“In the literature, the definition of middle class, just like ‘poverty,’ has been contentious. There is no single definition,” said Albert.

Economists often define it using income thresholds or purchasing power parity (PPP) dollars, while social scientists may use non-monetary measures.

Albert, citing 2021 data, detailed that Filipino families categorized within the middle-income class earned between approximately P24,060 and P144,360 per month. This income range covers those in the lower-middle, middle-middle, and upper-middle-income groups.

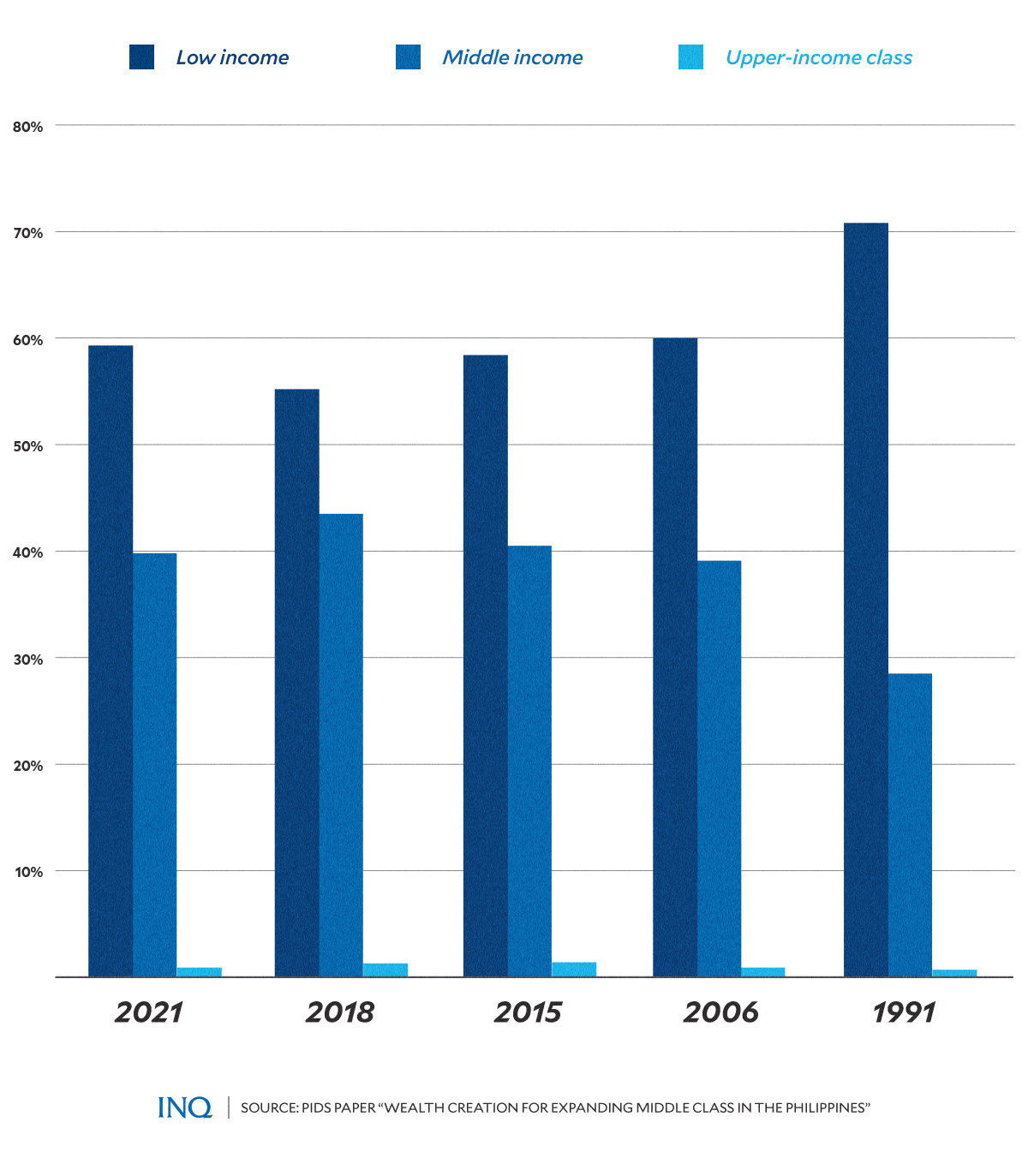

From 1991 to 2021, the share of middle-income class Filipinos grew from 28.5 percent to 39.8 percent. This growth, however, has not been consistent over time.

“[T]he COVID-19 pandemic appears to have reversed some of these gains, with the share of the middle-class falling to 39.8 percent in 2021,” the PIDS discussion paper said.

READ: 1.5M Filipinos seen sliding back to poverty due to COVID-19

Meanwhile, the majority of middle-income families were situated in urban areas, predominantly in regions such as the National Capital Region (NCR), CALABARZON (Cavite, Laguna, Batangas, Rizal, and Quezon), and Central Luzon. These three regions collectively represented 51.8 percent of the country’s entire middle-income population.

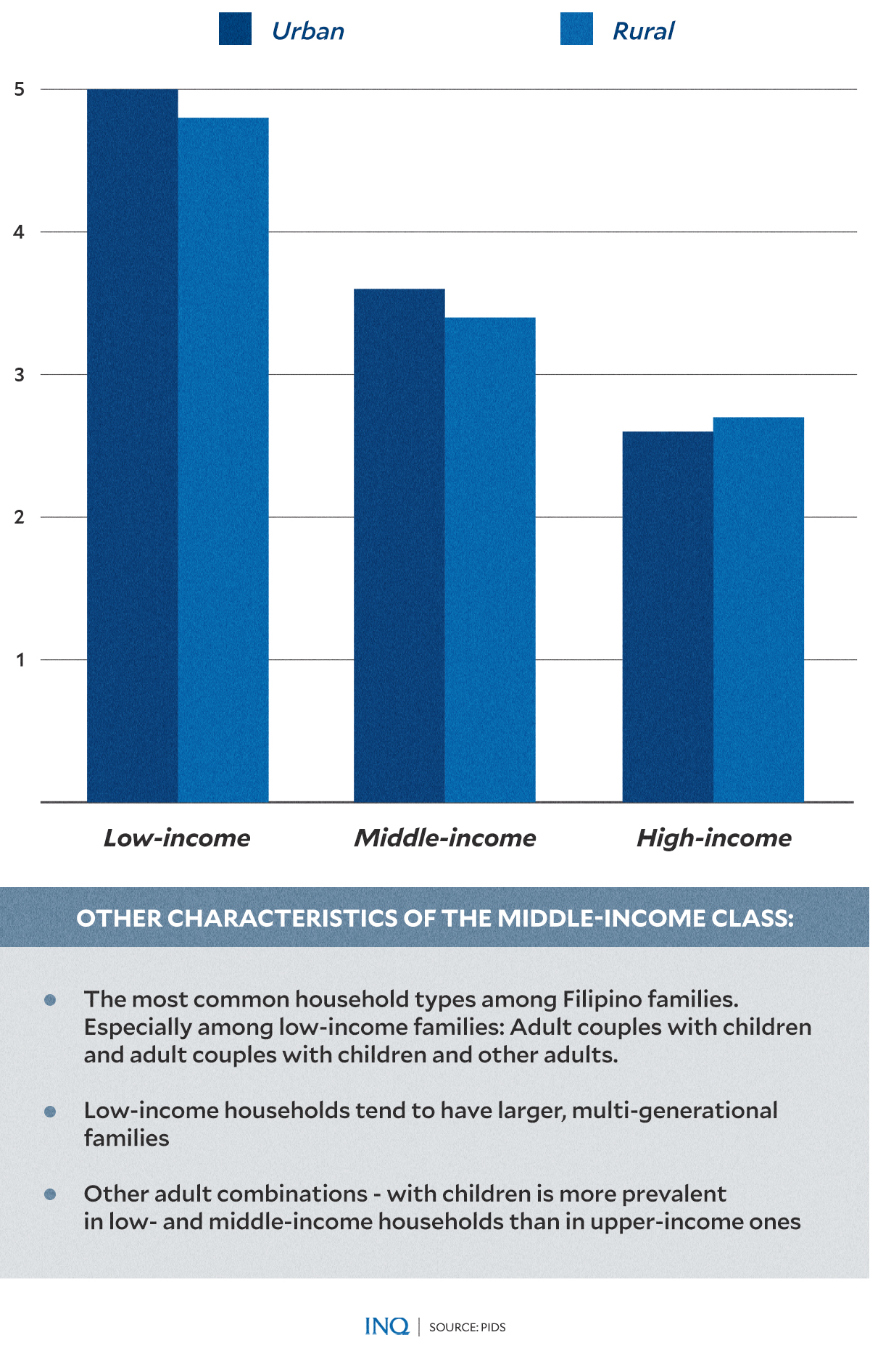

Albert and his fellow senior researchers observed that middle-class households generally have fewer members compared to low-income households. In 2021, the average household size for middle-class families was 3.6 members, whereas low-income households had an average of 5.0 members.

In contrast, high-income households were even smaller, with an average family size of 2.6 members that year.

Additionally, middle-class families had a lower dependency ratio, meaning they had fewer children and elderly individuals relative to the number of working-age adults compared to their low-income counterparts.

Spending, education

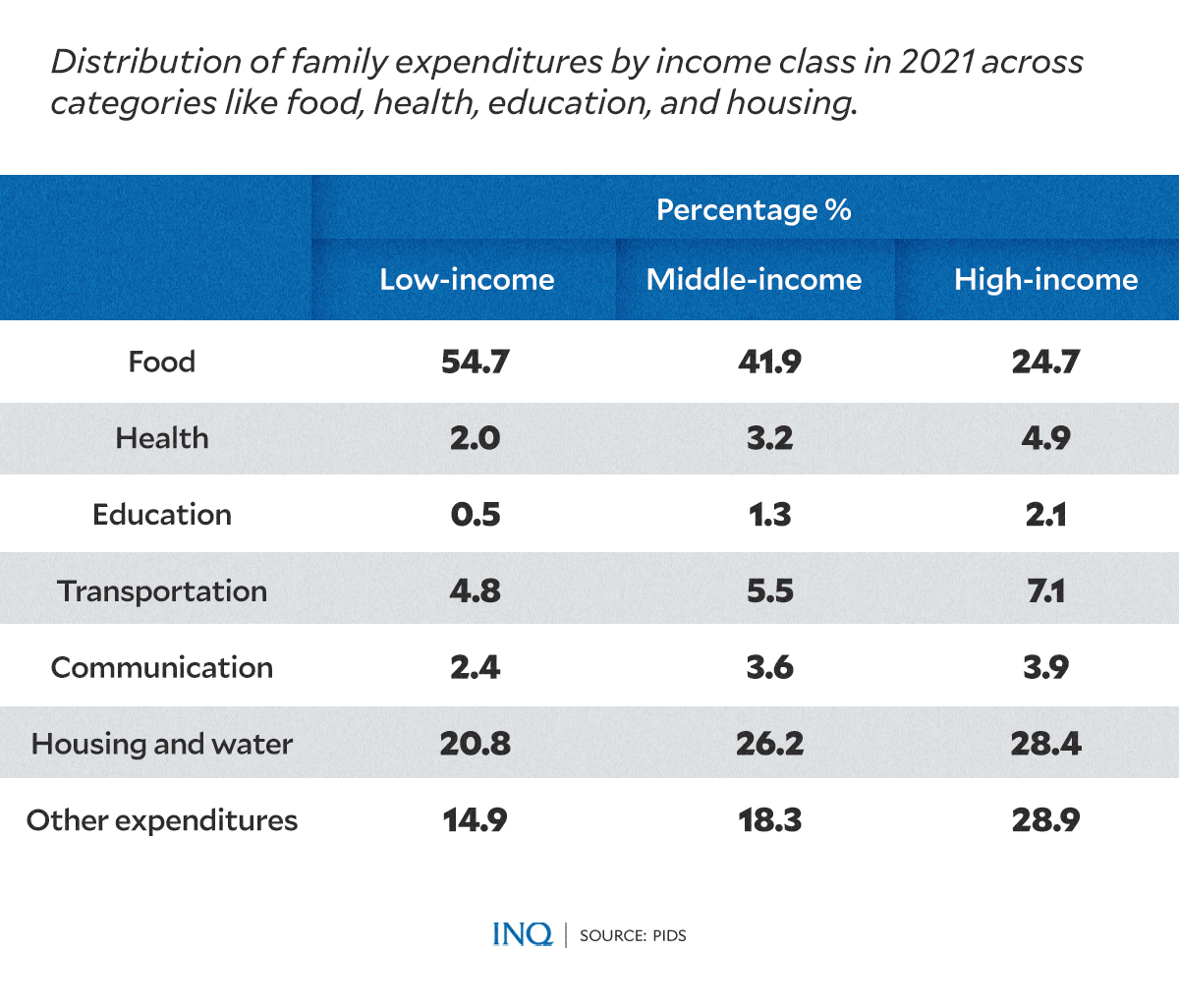

In 2021, middle-income families in the Philippines showed specific spending habits that reflect their position between low- and high-income groups.

Data presented by Albert revealed that these families allocated 3.2 percent of their total budget to health care — higher than the 2.0 percent spent by low-income households but less than the 4.9 percent spent by high-income families.

READ: WHO: Basic health services lacking in PH, Western Pacific

When it comes to essential needs, middle-income families spent a large portion of their budget on food, accounting for 41.9 percent of their total expenditures. At the same time, they dedicated more to housing (26.2 percent), transportation (5.5 percent), and communication (3.6 percent) compared to low-income households.

Spending on education was also a priority, with middle-income households allocating 1.3 percent of their budget to this category. This focus on education is evident in the educational attainment of middle-income adults, where 40.6 percent have completed a bachelor’s degree and 35.1 percent have finished lower secondary education.

However, despite these investments, gaps remain. Albert and his fellow PIDS senior researchers highlighted that in 2021, 24.1 percent of 5-year-olds from middle-income families were not in school.

READ: Unesco: 36 percent of PH families incur debts to send kids to school

While the overall non-enrollment rate for school-aged children in this group was low at 3.9 percent, it suggests that middle-income families may need more support and resources for early childhood education.

“Addressing the disparities in educational access and attainment between middle-income and low-income families is crucial for promoting inclusive growth and social mobility,” the discussion paper stressed.

Gaps in employment

Employment stability is crucial for the economic security of middle-income households in the Philippines.

According to the PIDS paper, unlike low-income families, which often rely on precarious, short-term jobs, a significant portion of middle-class households benefits from more stable, salaried employment.

In 2021, about 79.5 percent of employed individuals from middle-income households held permanent jobs, compared to 18.9 percent who were in short-term or casual employment. In contrast, 31.4 percent of employed individuals from low-income families had short-term or casual jobs, underscoring the greater employment stability experienced by the middle class.

Despite this relative stability, the senior research fellow stressed that unemployment remains a notable concern for the middle class. The unemployment rate among middle-income households (6.7 percent) is almost as high as that of low-income households (6.9 percent)

“While the unemployment rate has been a traditional metric of the labor market, in the Philippines, unemployment is not solely the problem of low-income families; it is also an issue among the middle class,” they wrote.

Women, in particular, face higher rates of unemployment in both the middle- and low-income classes compared to men, and they also have lower labor force participation rates across all income groups

OFW contribution to family income

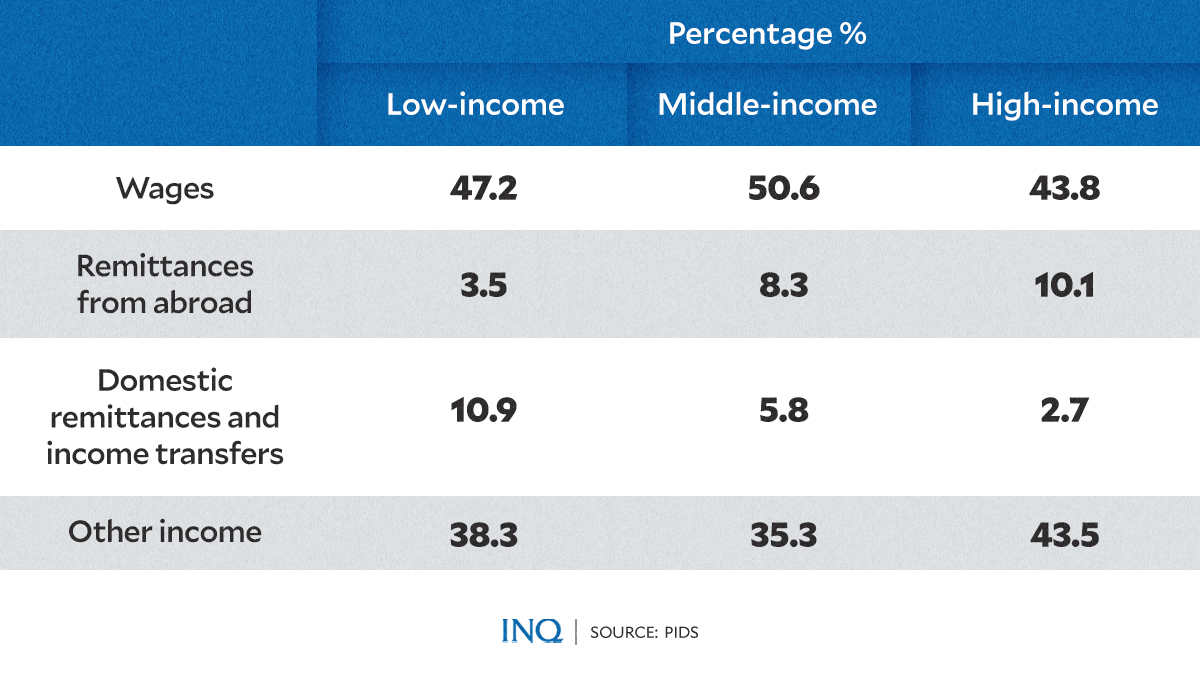

Beyond employment, income sources for middle-class families are diverse. A large portion of their income comes from wages and salaries (50.6 percent), with entrepreneurial activities contributing 24.0 percent and remittances from Overseas Filipino Workers (OFWs) making up 8.3 percent.

OFW remittances are especially significant for many middle-class families, providing a crucial financial buffer that can help maintain their economic status and manage unexpected expenses.

Albert, during his presentation, emphasized that “a majority of families with OFWs belong to the middle class.” Data showed that in 2021, approximately 74.7% of families with OFWs fall within the middle-class bracket, particularly in the middle-middle and upper-middle-income segments.

However, the PIDS researchers noted that relying heavily on remittances also poses risks.

“[I]t is important to note that the reliance on remittances from OFWs may also have some drawbacks. The separation of family members due to overseas employment can have social and emotional consequences,” they explained.

“Additionally, the dependence on remittances may make families vulnerable to economic shocks in the host countries where OFWs are employed,” the discussion paper authors added.

Challenges

Even before the pandemic, middle-class families were already at risk from economic disruptions, and the COVID-19 crisis only made these challenges worse.

“The COVID pandemic has had a significant impact on the middle class in the country. Many middle-class households have experienced child losses, reduced incomes, and increased expenditure on health and education,” Albert said.

“The pandemic has highlighted the vulnerability of middle-income class households, particularly those in the lower middle-income segment,” he continued.

Moreover, regional disparities further complicate efforts to strengthen the middle class. While the NCR and CALABARZON regions have significant middle-class populations, other regions still have large low-income populations.

Despite these challenges, Albert said there is optimism about the middle class rebounding to around 45 percent of the population by 2023, given the recent reduction in poverty rates — as previously stated by the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA).

(Next: Pathways for middle-class expansion; growing and strengthening middle class.)

RELATED STORIES:

Neda: PH can still achieve upper-middle income status by 2025

Angara: Proposed budget remains faithful to make PH middle-income nation

Metro Manila’s middle-class Gen Zs, millennials feel impact of inflation