EXPLAINER Leptospirosis kills, how to avoid it

MANILA, Philippines—As Super Typhoon Carina unleashed its fury on the Philippines, it brought massive flooding to Metro Manila, exacerbated by the southwest monsoon (habagat). The deluge has created an ideal environment for a silent yet deadly threat: leptospirosis.

Often overshadowed by other flood-related diseases, this bacterial infection has claimed numerous lives in recent weeks and is fast becoming a significant public health concern.

With streets transformed into rivers contaminated by rat and animal urine, the risk of contracting this killer disease has surged, prompting warnings from public health officials.

What is leptospirosis?

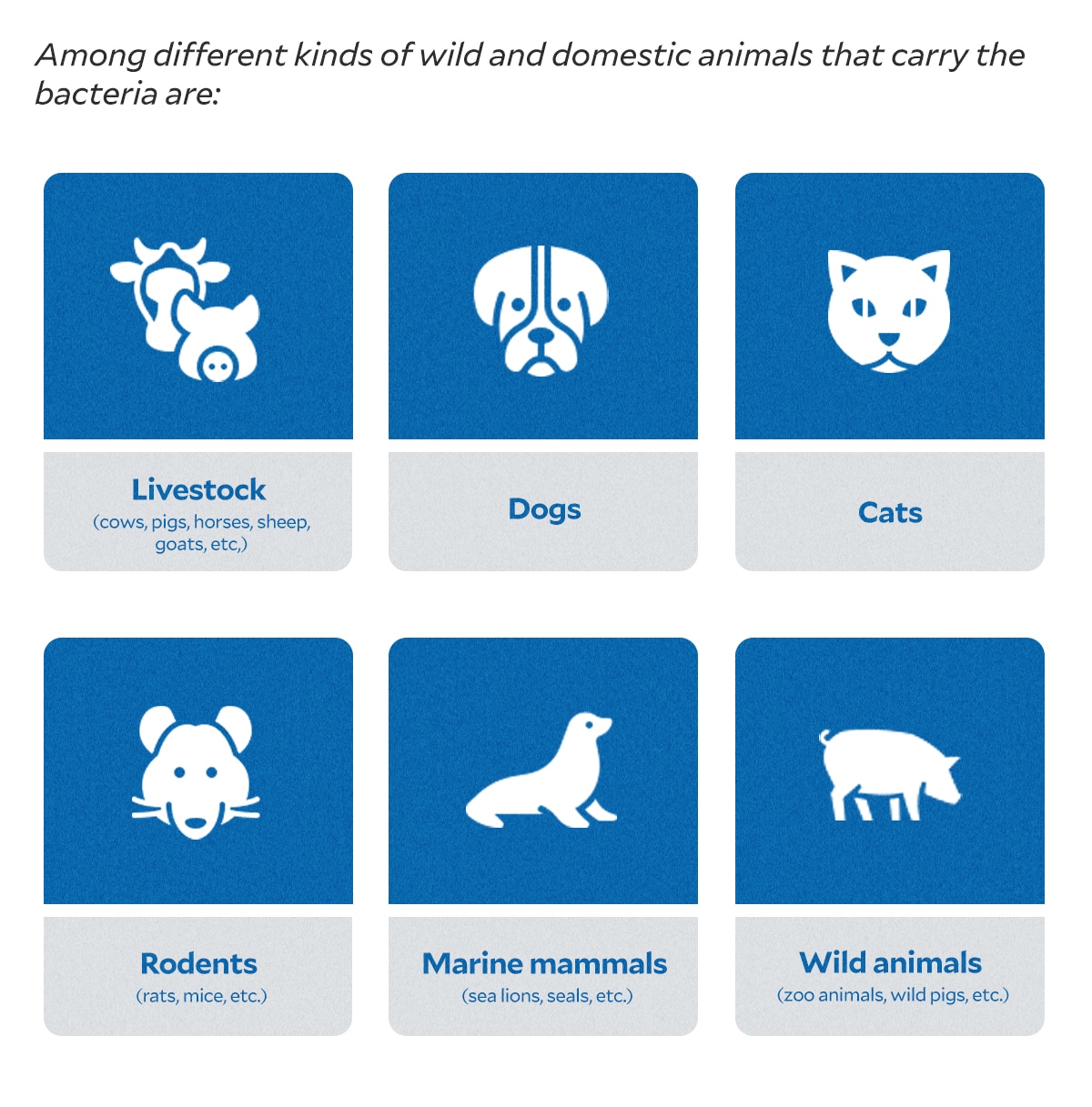

Leptospirosis is a bacterial infection caused by the leptospira bacteria, which is commonly found in the urine of infected animals such as rats, livestock, dogs, cats, and even some marine mammals.

The bacteria can survive in water or soil for weeks or even months, making floodwaters potential breeding grounds for the disease.

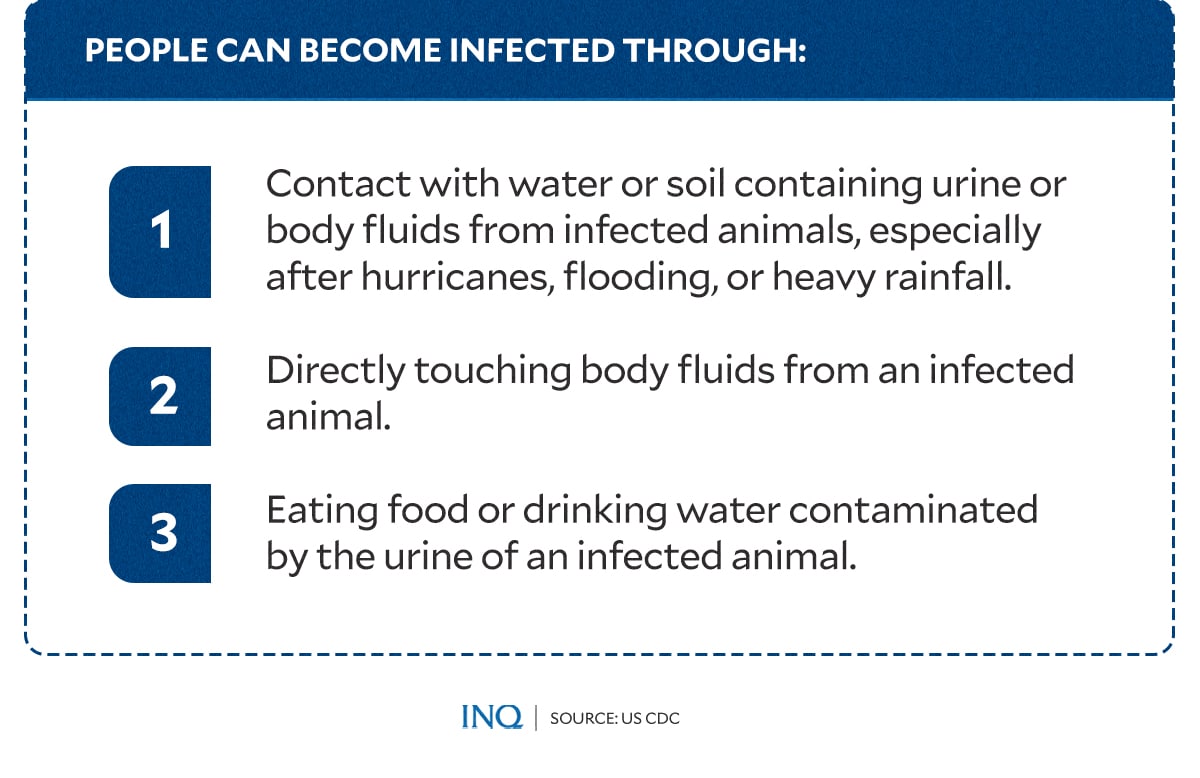

People may become infected through:

- Contact with urine or body fluids from infected animals, except saliva; or

- Contact with water, soil, or food contaminated with the urine of infected animals.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) explained that the bacteria can enter the body through the skin, especially if there’s a break in the skin caused by a cut or scratch.

It can also enter through the mucous membranes of the eyes, nose, or mouth. Ingesting contaminated water can also lead to infection. However, one of the most common causes of leptospirosis is exposure to contaminated waters such as floodwaters.

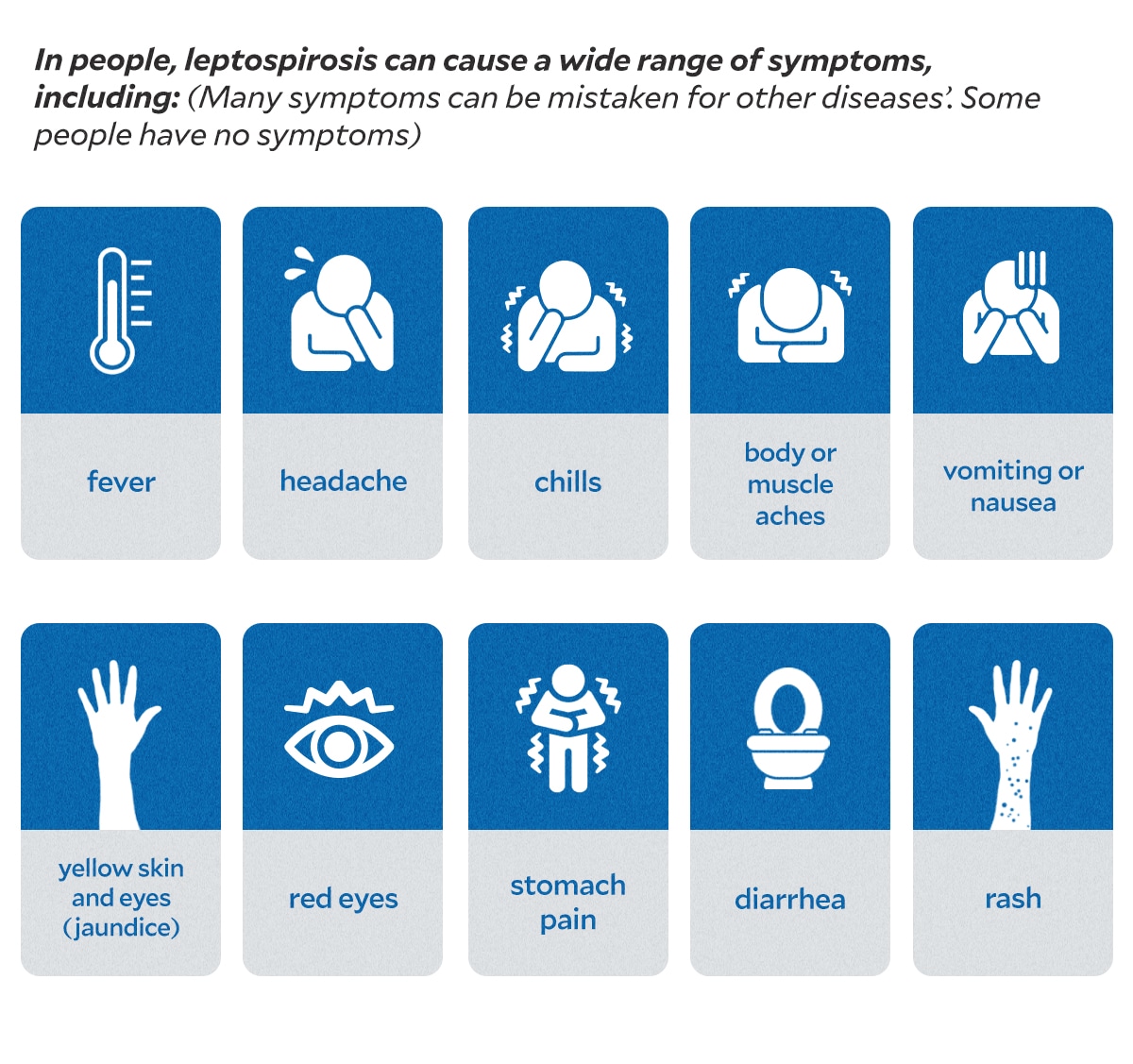

In humans, leptospirosis can present a wide range of symptoms that are often mistaken for other illnesses. Early signs include fever, chills, headache, muscle aches, vomiting, and diarrhea — symptoms that closely resemble those of the flu.

In some instances, infected individuals may not exhibit any symptoms at all.

However, the Department of Health (DOH) warns that in severe cases, infected persons may experience:

- Jaundice (yellowing of the skin and eyes)

- Dark-colored urine

- Low urine output

- Severe headache

Symptoms typically appear 2 to 30 days after exposure to the bacteria. The disease may progress through two phases:

- First Phase: Individuals may experience fever, chills, headache, muscle aches, vomiting, or diarrhea. Symptoms may subside temporarily, only to return with more severity.

- Second Phase: The more severe phase may involve kidney or liver failure, or inflammation of the membrane surrounding the brain and spinal cord (meningitis).

The illness can last from a few days to several weeks. Without treatment, recovery may take several months. In severe cases, the disease can lead to life-threatening complications and even death.

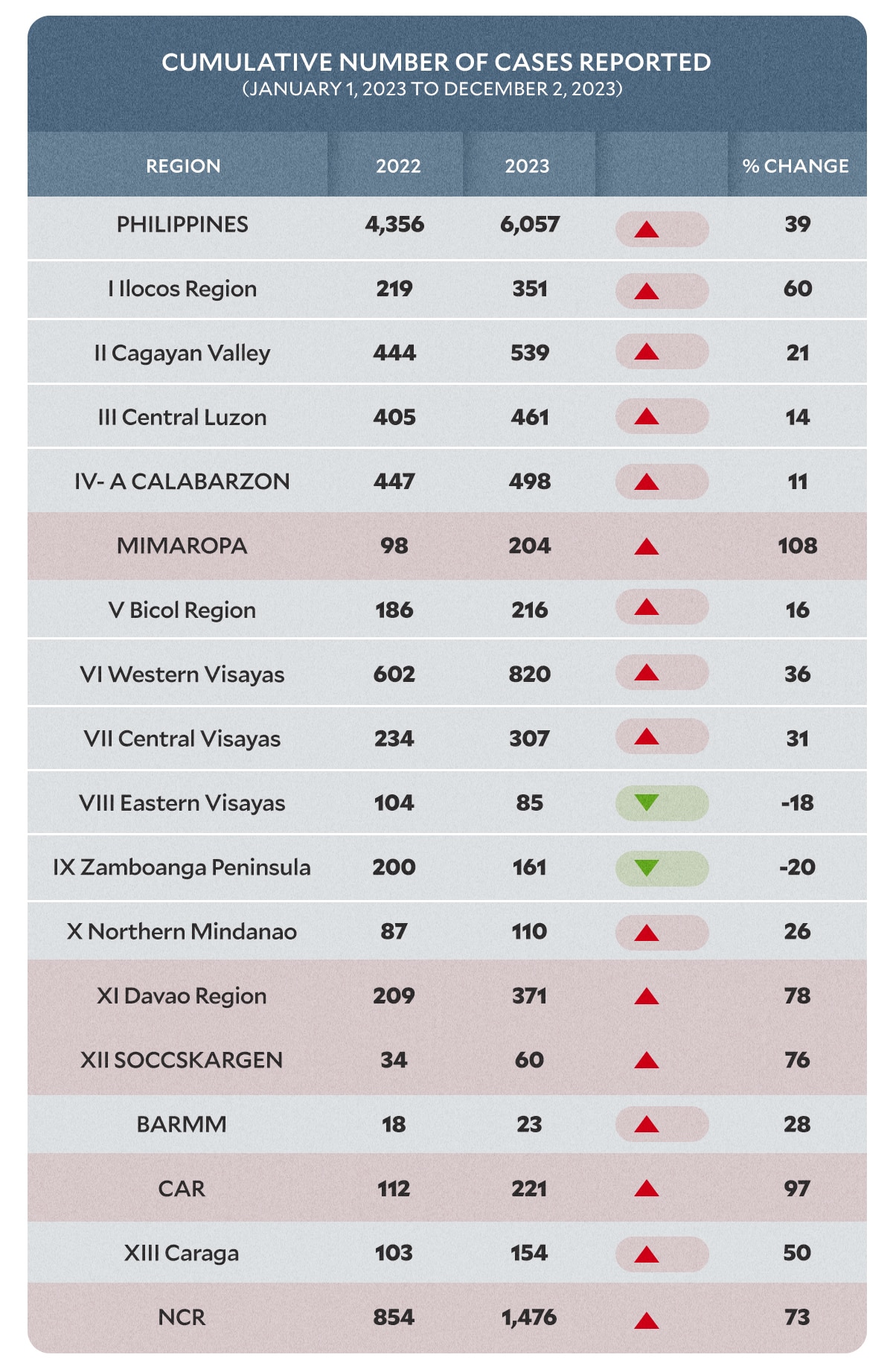

Surge in cases

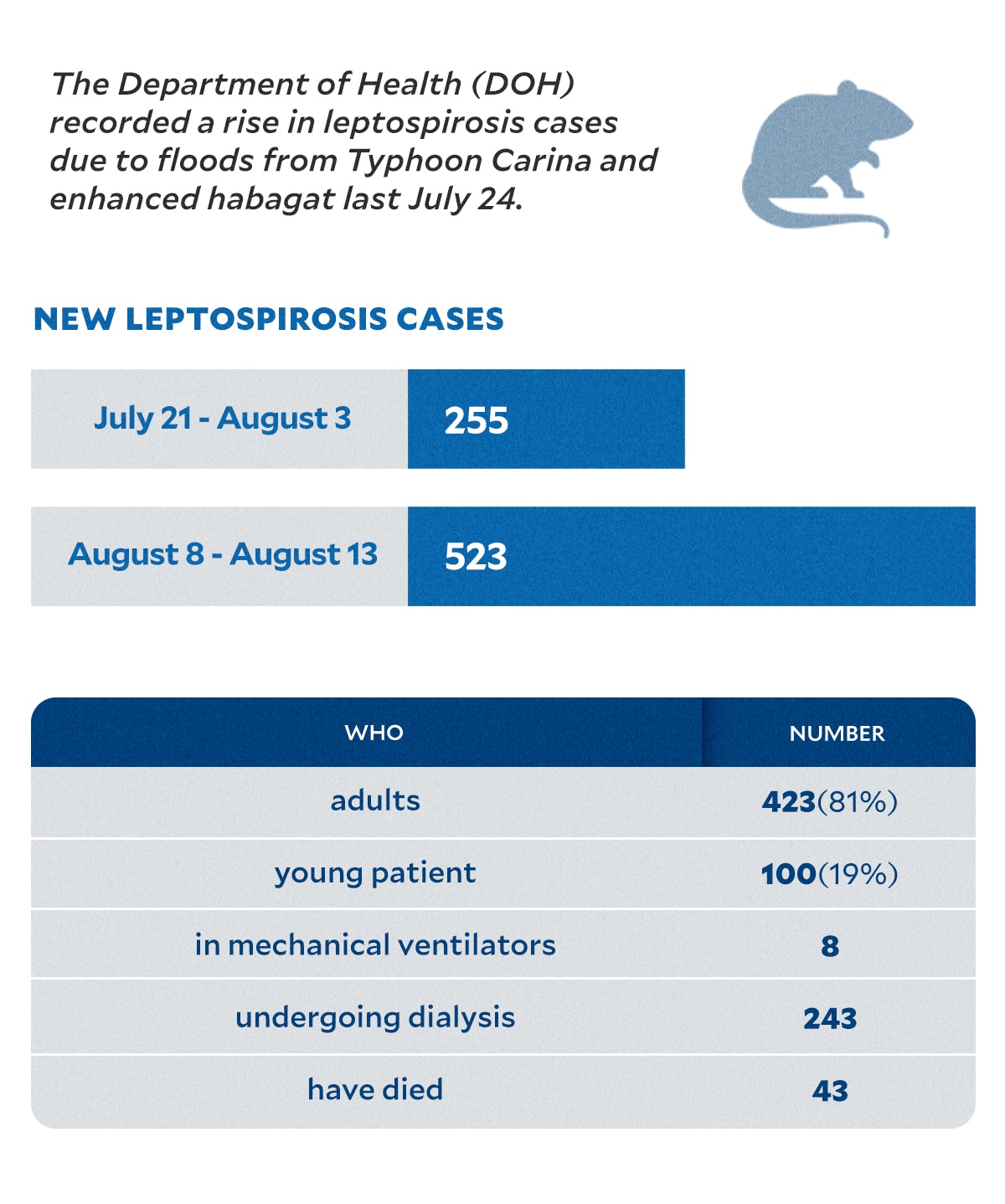

According to DOH, the country has seen a worrying spike in leptospirosis cases following the floods brought by Carina and the enhanced habagat.

Between July 21 and August 3, the health department recorded 255 new cases of leptospirosis, marking a 17 percent increase from the 217 cases reported in the preceding period from July 7 to 20.

READ: Leptospirosis cases on the rise with 255 new patients, says DOH

Most recent data showed that between August 8 and August 13 alone, 523 new cases of leptospirosis were documented. Of these, 81 percent, or 423 patients, were adults, while 19 percent, or 100, were young patients.

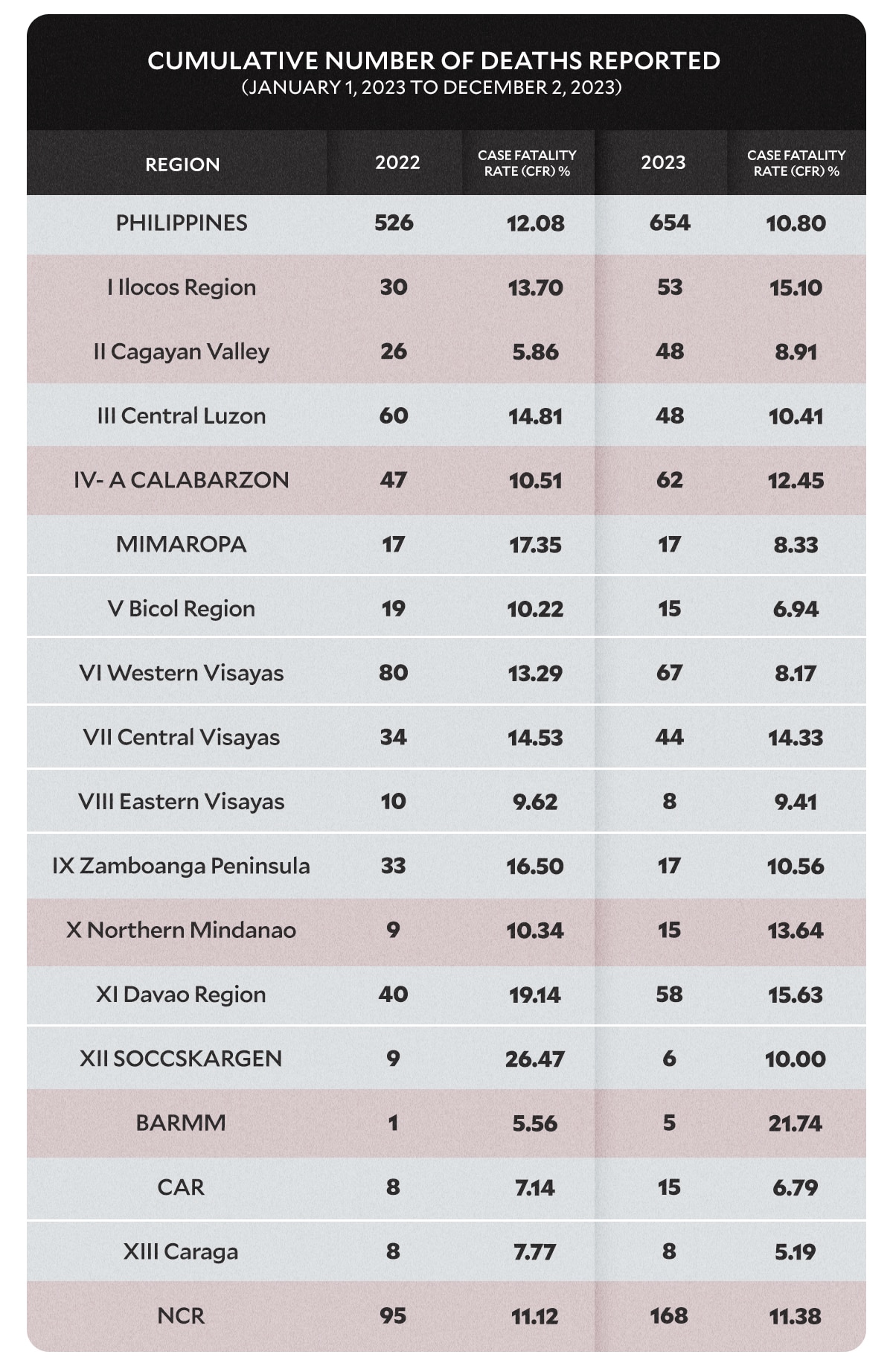

The disease has led to severe complications in many cases: 8 patients are currently on mechanical ventilators, 243 are undergoing dialysis due to kidney failure, and 43 have already died.

“This was the week when the number of patients at the National Kidney and Transplant Institute (NKTI) and San Lazaro Hospital surged,” said DOH spokesperson Albert Domingo.

Despite the rise in cases, the overall number of leptospirosis cases from January 1 to August 3 this year (2,115 cases) is still 23 percent lower than the 2,757 cases reported during the same period last year.

However, the DOH warned that epidemiologists remain cautious in interpreting trends, as there may be delays in reporting.

PH: No stranger to outbreaks

Historically, the Philippines is no stranger to leptospirosis outbreaks, particularly in the aftermath of severe weather events. On average, the country experiences around 20 storms every year.

Several studies on leptospirosis outbreaks in the Philippines following flooding incidents have highlighted one of the most significant outbreaks in recent history.

This occurred in September 2009, when Tropical Storm Ondoy (Ketsana) unleashed a month’s worth of rainfall in just six devastating hours, leading to widespread flooding and submerging a vast portion of Metro Manila within 24 hours.

READ: Special Report on Storm ‘Ondoy’: Marikina remembers ‘end of the world’

On average, the Philippines records around 680 cases of leptospirosis and 40 related deaths annually. However, after the severe rainfall in 2009, the number of suspected leptospirosis cases surged dramatically, largely due to people wading barefoot in floodwaters.

Within two weeks following the typhoon, 2,292 suspected cases were reported, along with 178 fatalities (a 7.8 percent mortality rate), leading the DOH to declare a leptospirosis outbreak.

“An increase in the number of cases of leptospirosis in affected areas resulted in a significant burden on existing health resources, mainly on the provision of chemoprophylaxis and in the management of the severe form of the disease (Weil’s syndrome), which typically requires admission in an intensive care unit,” a 2012 study noted.

Hospitals told to prepare

Earlier this month, the DOH instructed all its hospitals in the National Capital Region (NCR) to activate their “leptospirosis surge capacity plan” in response to the rising number of cases.

In a memorandum, DOH Officer-in-Charge Undersecretary Gloria Balboa emphasized the need to expedite referrals. She directed all DOH hospitals to use standardized referral forms available online and to update the Health Emergency Management Bureau’s operations center with the names and contact details of their referral focal persons by August 13.

“Due to the increasing leptospirosis cases in NCR and in preparation for further anticipated surges, our ability to respond promptly and effectively is being tested, particularly in augmenting both human and material resources, such as deploying health workers to manage the surge and expanding critical care capacity,” Balboa stated.

In Quezon City, the National Kidney and Transplant Institute (NKTI) has recorded a significant influx of leptospirosis cases, with 67 patients admitted as of August 9, including 11 in the pediatric section. The hospital’s emergency room is currently operating over capacity.

READ: Make plans for leptospirosis surge, DOH tells hospitals

In response, NKTI has converted its gymnasium into a leptospirosis ward capable of accommodating 40 patients and plans to open an additional ward for 15 more. However, all backup beds have been used, and several patients are now on cots and wheelchairs.

Although NKTI has the capacity to take in more patients, it urgently needs additional staff. The hospital has requested for 20 more nurses and 10 internal medicine doctors from the DOH, and has also issued a call for volunteer nurses.

The DOH continues to remind the public that antibiotic prophylaxis against leptospirosis is widely available by prescription. The price freeze for doxycycline remains in effect until September 23, and free capsules are available at government health centers and hospitals nationwide.

READ: DOH told: Be aggressive in fight vs leptospirosis amid rising cases

The health department warned that individuals who have had contact with floodwaters should not wait for symptoms to appear and are advised to consult a doctor or health center immediately.

Surge in cases: A ‘behavior problem’

Health Secretary Teodoro Herbosa stressed that the recent surge in leptospirosis cases is not due to a “communication problem” but rather a “behavioral” issue.

“We need a change in behavior. I’d like to discuss with the Department of Education how to teach children early on that they should not swim in flood waters,” said Herbosa.

According to Herbosa, the number of leptospirosis cases reached “epidemic thresholds” in the NCR, particularly in Quezon City and Manila, as well as in Central Luzon and Calabarzon (Cavite, Laguna, Batangas, Rizal, Quezon) regions, weeks after severe flooding due to the southwest monsoon and Super Typhoon Carina (international name: Gaemi) in July.

He recommended that all flood-prone local government units (LGUs) legislate a ban on swimming in dirty floodwater, as he expressed frustration with Filipinos’ failure to heed regular advisories intended to prevent the spread of the deadly disease.

“I recommend, especially to flood-prone local government units, that they should pass ordinances that prohibit swimming and playing in floodwater. The local chief executives should strictly enforce these,” he said.

READ: Metro mayors urged to ban swimming in floods

Herbosa also expressed his intention to engage with the Metropolitan Manila Development Authority (MMDA) on improving solid waste management. He emphasized that better waste management is crucial since rats, which are carriers of leptospirosis, thrive in garbage.

“[W]hen solid waste management is poor, the rodent population numbers increase. When the rodent population numbers increase, leptospirosis cases will increase,” he said.

“We should be able to control this. We are a city below sea level so it’s always flooded but if we keep our solid waste management and rodent population low, [we] shouldn’t be having this upsurge of leptospirosis cases a week after or two weeks after floods,” he noted.

Treatment and prevention

Leptospirosis, according to DOH, may be treated by taking antibiotics prescribed by a doctor.

“Early recognition and treatment within two days of illness to prevent complications of leptospirosis, so early consultation is advised,” DOH said.

Dr. Rafael Castillo, of the Manila Doctors Hospital, cited in a previously published article some of the medical advice he received from Dr. Dolores Banzon of the Philippine Society of Nephrology.

“If you waded in floodwaters just once (single exposure), and you don’t have cuts or skin lesions, you’re considered low risk. You just need to take a single dose of doxycycline 100 milligrams, two capsules single dose within 24 to 72 hours,” Castillo wrote, citing Banzon.

“If you have some cuts or lesions in your skin, you’re considered moderate risk. Take doxycycline 100 mg, two capsules for 3-5 days. Start ASAP (as soon as possible) and no later than 72 hours after,” he continued.

“If you have continuous exposure, with or without skin cuts or lesions, you’re at high risk for infection. Take prophylactic doxycycline 200 mg once a week until you stop wading in the flood,” the doctor added.

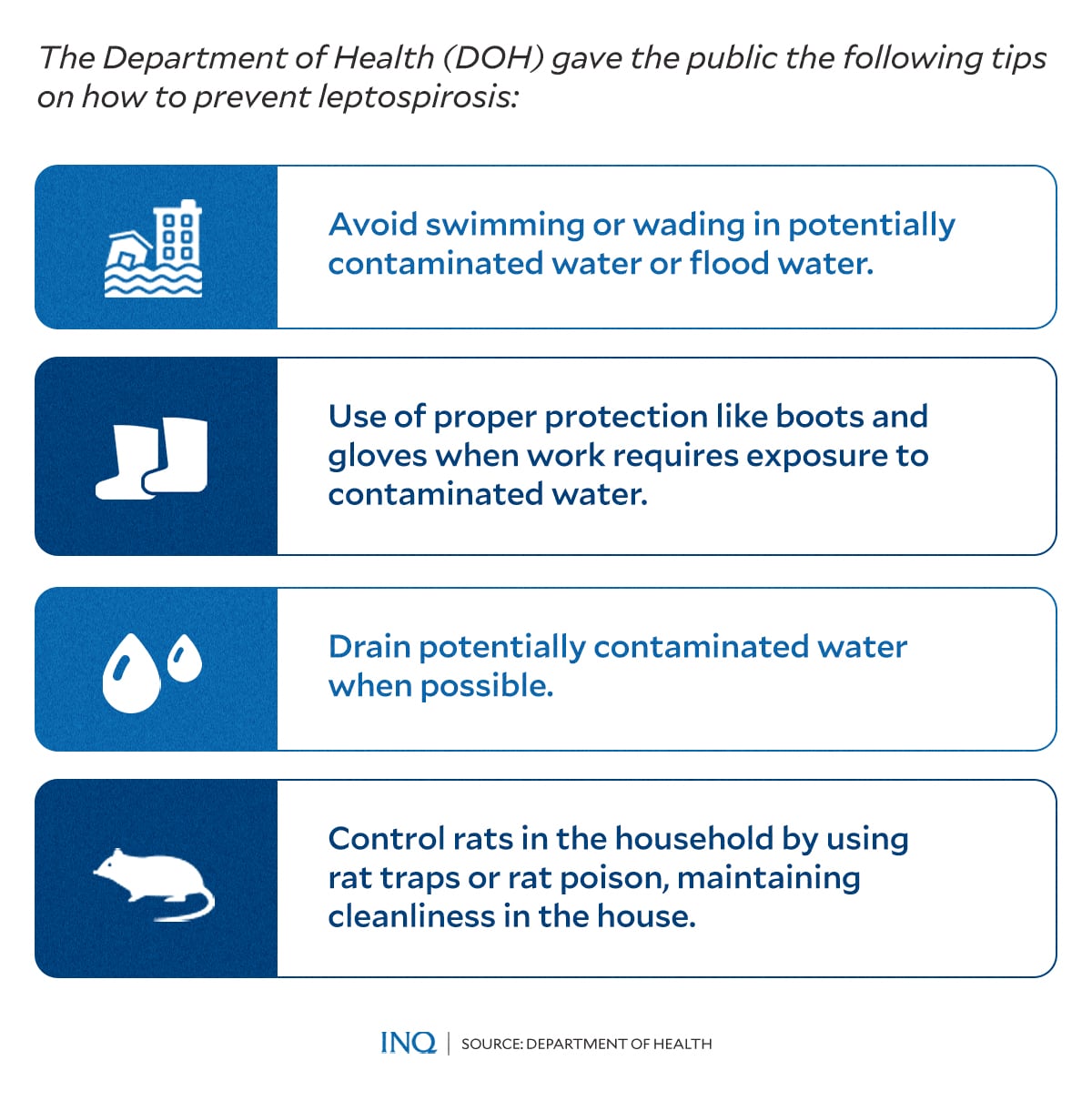

The DOH has been repeatedly giving the public the following tips on how to prevent leptospirosis:

- Avoid swimming or wading in potentially contaminated water or flood water.

- Use of proper protection like boots and gloves when work requires exposure to contaminated water.

- Drain potentially contaminated water when possible.

- Control rats in the household by using rat traps or rat poison, maintaining cleanliness in the house.

- Cover cuts and scratches with waterproof bandages.

RELATED STORIES:

Red Cross team deployed amid leptospirosis surge

Coordinate efforts vs leptospirosis