Heritage structures losing resilience vs deeper floods, climate change

MANILA, Philippines––A 17th-century church in Pampanga, the San Agustin Parish in Lubao, was first located in Barrio Santa Catalina in 1572 but was moved to its present site 30 years later because of what the National Historical Commission of the Philippines (NHCP) described as “yearly floods.”

But last week, as Super Typhoon Carina enhanced monsoon rains and triggered flooding in Metro Manila and some provinces in Luzon, including Pampanga, the church in Lubao, as well as other Important Cultural Properties (ICPs) and National Historical Landmarks (NHLs), were inundated.

- San Bartolome Parish, Malabon City

Declared as an ICP, especially for what the National Museum of the Philippines (NMP) described as its “architectural wonders,” including eight imposing ionic columns, the 410-year-old church, which is the oldest in the Diocese of Kalookan, was established by the Augustinians in 1614, with the present structure “created and completed” in 1813.

- Barasoain Church, or Our Lady of Mt. Carmel Parish, Malolos City, Bulacan

With construction commencing in 1885 and completed in 1888, the Barasoain Church is a “remarkable representation of the period when Baroque architecture gained popularity in Spanish-built structures throughout the Philippines.”

The church was declared as a National Shrine by Presidential Decree No. 260.

Article continues after this advertisementAccording to its website, Barasoain Church’s history is “deeply intertwined” with the history of the Philippines itself. It is considered as the “Cradle of Democracy in the East” since it was in this church where significant events that established the First Philippine Republic took place.

Article continues after this advertisement- St. Francis of Assisi Parish, Meycauayan City, Bulacan

Once “home” to the Franciscan saint Pedro Bautista, the over 350-year-old church is one of the oldest in the province of Bulacan. It was built in 1668, and in the 1980s, it became a haven for activists who were blocked by the military from entering Metro Manila to commemorate the death anniversary of slain Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino Jr.

The St. Francis of Assisi Church in Meycauayan City. PHOTO COURTESY OF ST. FRANCIS OF ASISI PARISH/FACEBOOK

- The Metropolitan Theater, City of Manila

Designed by Filipino architect Juan Arellano, the Metropolitan Theater, which was one of Manila’s iconic landmarks when it was considered the “Paris of Asia”, was completed in 1931 but damaged by World War II. It was restored in the 1970s and was opened once again in 1978. However, it fell into disuse in the late 1980s.

The building, which was declared as an NHL and National Cultural Treasure, especially because of its grand architectural design and unique Art Deco style, was closed in 1996 but was opened again in 2021 after extensive rehabilitation and restoration works that started in 2017.

Intensifying streams

According to the website of the local government of Lubao, San Nicolas I, where the church is located, is one of the town’s eight “easily flooded barangays.”

Back in 2016, the San Agustin Parish was likewise hit by flooding, prompting church officials to place sandbags at the church entrance.

READ: Addressing Pampanga, Bulacan flooding

Meliton Juanico, a retired professor of geography at the University of the Philippines’ College of Social Sciences and Philosophy, had said in an INQUIRER column that aside from heavy rainfall, there are several reasons for the flooding in Pampanga, as well as in Bulacan, especially in the last few years.

- Massive deforestation of Sierra Madre mountains

- Silting of rivers, especially because of soil erosion, the ash fall and lahar from Mount Pinatubo’s explosion in 1991, and garbage discarded by residents

- Subsidence, or sinking of the ground

In Metro Manila, where a string of heritage structures, including the University of Sto. Tomas and De La Salle University, had been inundated, too.

The Department of Public Works and Highways linked the intense flooding to the region’s overpopulation and overcapacity of its drainage systems.

Back in 2013, the Associated Press reported that Metro Manila is located in a catch basin between Manila Bay and Laguna de Bay, so it was built on waterways, canals and creeks “that have for centuries channeled floodwaters into the sea.”

However, half the 40 kilometers, or 25 miles, of narrow waterways and canals that would drain rainwater are now gone.

READ: What’s making the floods worse in Manila?

“[They] have been lost, cemented or paved over,” architect and urban planner Paulo Alcazaren had said, stressing that a lot of the remaining ones are clogged with garbage and ill-maintained. These waterways were constructed and modified throughout the Spanish colonial period.

READ: Climate crisis to turn Manila, other Asian cities into bodies of water

According to a 2021 report by Greenpeace East Asia, relentless and extreme sea level rise because of climate change is triggering stronger typhoons that could soon sink Manila and displace millions of people and destroy economies, with at least 87 percent of its land expected to get hit in 2030.

Threatened ‘wealth’

As pointed out by Gerard Lico, an architect working as a heritage conservationist, old structures are “at risk”, especially when heavy rains lead to intense flooding, stressing that the “trend of escalating rainfall poses a major threat to heritage structures and sites, especially since water-induced damage may be irreversible.”

While regarded as “silent witnesses to history,” old structures, such as centuries-old churches in Metro Manila and the provinces of Pampanga and Bulacan, will not always be resilient, especially against calamities such as flooding, and even just heavy rainfall.

According to the US Department of Interior’s “Guidelines on Flood Adaptation for Rehabilitating Historic Buildings,” flood risk has long been a major challenge for a lot of historic buildings, and that now, flooding events are occurring at an increased frequency and magnitude.

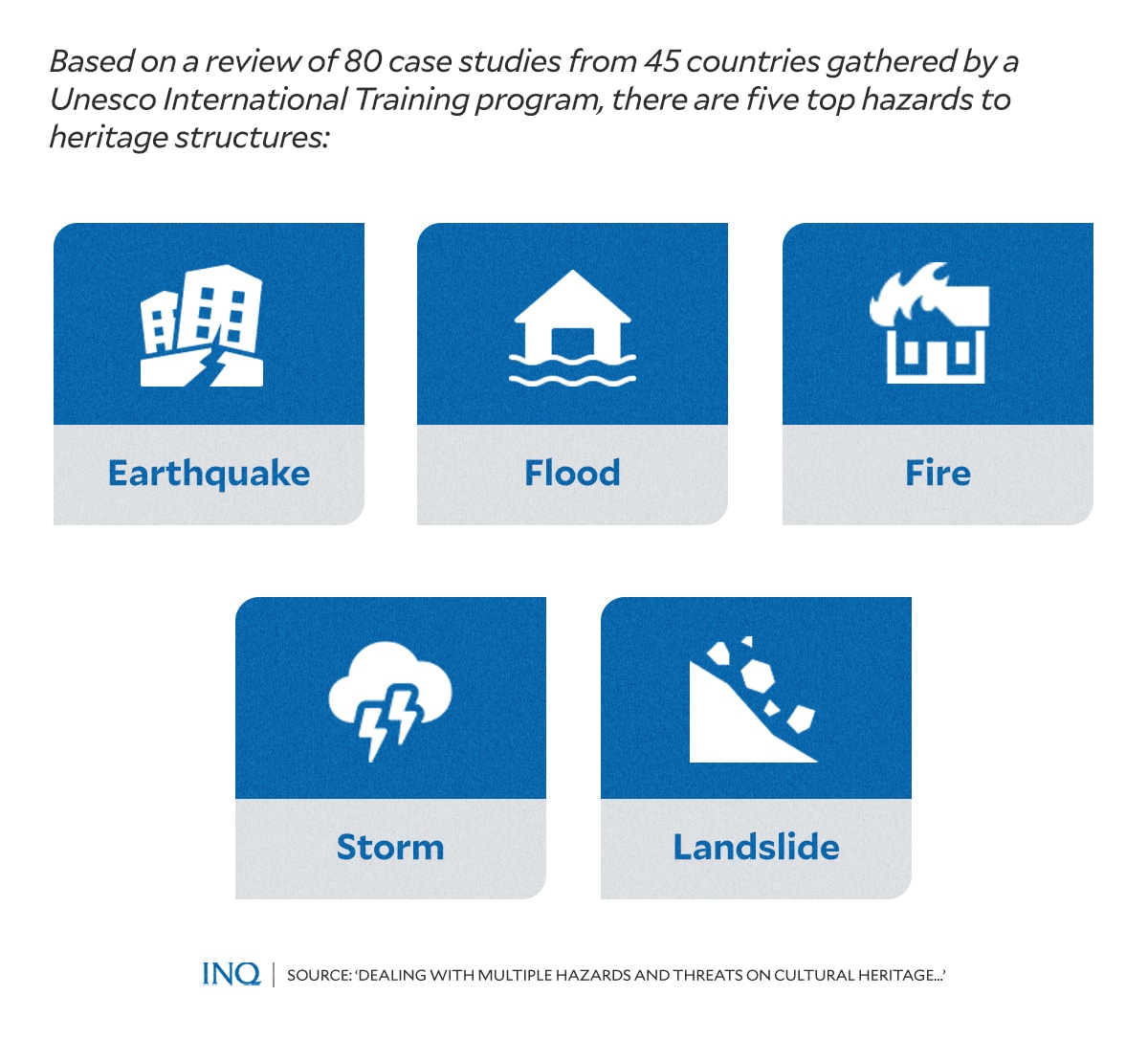

As stated in Bosher et al.’s “Dealing with Multiple Hazards and Threats on Cultural Heritage Sites: An Assessment of 80 Case Studies” in 2019, which was reiterated in a study by Loreto et al., flood, earthquake, fire, storm, and landslide are the “top five hazards to heritage structures” all over the world.

Looking back, heritage churches and houses in Bohol and Lanao del Sur were damaged in 2021, too, because of the flooding that was triggered by Typhoon Odette, a “deadly and destructive typhoon” that “brought torrential rains, violent winds, landslides, and storm surges.”

Based on the study “Impact of Floods on Heritage Structures” by Miloš Drdácký and published in the Journal of Performance of Constructed Facilities, “flooding leads to the loss of historical monuments, devastation of historic sites, changes in the cultural landscape, and […] disappearance or substantial distortion of intangible heritage.”

Lico, who was one of those who worked to preserve and conserve the Metropolitan Theater, however, pointed out to INQUIRER.net that even heavy rainfall “is a difficult challenge for historic buildings whose aged gutters, downpipes and drains cannot cope with increased volumes of water.”

‘Protect our heritage’

“Emergency and flood crisis management plans should be crafted in response to the high frequency of floods in light of climate change,” Lico said as he stressed that in the Philippines, “proactive planning for heritage properties is usually absent” despite the high possibility of flooding.

He said that “it is imperative to plan ahead and position these buildings to be resistant and resilient to flooding and water damage,” pointing out that “we have to devise ways to deflect flood waters through landscape elements and trenching.” When these concerns are addressed, “our heritage can stand longer,” he said.

“Flood probability is very high and heritage structures and sites are vulnerable thus it is better to plan ahead and make the structure resistive and resilient to flooding,” he said.

As pointed out by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (Unesco), all world heritage properties can be exposed to one or more types of disaster, including flooding: “Over the last few years, natural and human-induced disasters have caused enormous losses to World Heritage properties,” Unesco said.

“Climate change may also increase [the] impacts of disasters on World Heritage cultural properties through its effects on significant underlying risk factors. Any increase in soil moisture, for example, may affect archaeological remains and historic buildings, thereby increasing their vulnerability to natural hazards such as earthquakes and floods,” it said.

Based on the US Department of Interior’s “Guidelines on Flood Adaptation for Rehabilitating Historic Buildings, these are the most common treatments that can be considered to create “more resilient” structures, described using definitions provided by the Federal Emergency Management Agency:

- Planning and Assessment for Flood Risk Reduction

- Temporary Protective Measures

- Site and Landscape Adaptations

- Protect Utilities

- Dry Floodproofing

- Wet Floodproofing

- Fill the Basement

- Elevate the Building on a New Foundation

- Elevate the Interior Structure

- Abandon the Lowest Floor

- Move the Historic Building

As Unesco stressed, “although heritage is usually not taken into account in global statistics concerning disaster risks, cultural and natural properties are increasingly affected by events which are less and less ‘natural’ in their dynamics, if not in their cause.”

But in the face of these challenges, “the number of World Heritage properties that have developed a proper disaster risk reduction plan is surprisingly low.”

RELATED STORY: Centuries-old Bulacan church inundated by monsoon-induced floods