Groups urge PH to restore mangroves in abandoned fishponds

MANILA, Philippines—In the face of climate change’s escalating damage, Oceana, an international organization, and a coalition of scientists and civic groups are urging the government to breathe new life into abandoned fishponds by restoring them to thriving mangrove ecosystems.

In a letter sent last December to Agriculture Secretary Francis Tiu Laurel and Environment Secretary Antonia Yulo Loyzaga, more than 10 global and local conservation groups highlighted the National Climate Change Action Plan’s (NCCAP) emphasis on critical measures for boosting the resilience of communities and ecosystems against climate change.

“The protection and rehabilitation of critical ecosystems, such as mangroves, beach forests, and coastal wetlands, and the restoration of their ecological services contribute to our international commitments…,” the letter read.

The framework targets the effective conservation and management of at least 30 percent of the world’s lands, inland waters, coastal areas, and oceans.

The groups noted that the country has about 450,000 hectares of lush mangrove forests recorded in 1918.

Article continues after this advertisementUnfortunately, over half of these have disappeared, mainly because of their conversion to fishponds and other coastal projects, making the Philippines the second in rank in Southeast Asia for mangrove depletion.

Article continues after this advertisement‘Inconsistencies in policies’

In the letter, the signatories stressed several laws and policies aimed at protecting mangroves and the repurposing of fishponds to their original status as mangroves.

The Revised Forestry Code of the Philippines, also known as Presidential Decree No. 705, was strengthened by Republic Act 7161, which made cutting down mangroves illegal. In 1998, the Philippine Fisheries Code was introduced, specifying in Sections 46 and 49 that all abandoned fishponds must be reverted to their original mangrove state.

“The law is clear that the grant of Fishpond Lease Agreements come with mandatory conditions, such as automatic reversion back to mangroves once the fishponds have been abandoned, or remain undeveloped or underutilized,” said lawyer Gloria Estenzo Ramos, Oceana vice president.

“However, the implementation of this provision remains slow,” Ramos added.

Ramos pointed to inconsistencies in the implementation of laws and the policies by the DENR and the Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources of the Department of Agriculture on abandoned fishponds.

The conservation groups tagged BFAR Fisheries Administrative Order (AO) 115, issued on March 28, 2011, as among the rules that are inconsistent with mangrove protection. The AO provides a framework for abandoned fishponds to be used as productive assets run by community-based management systems through fishers’ groups and cooperatives.

They added that in 2012, BFAR issued Fisheries Administrative Order 197-1 that sets out a process to cancel FLAs and promoted stewardship contracts for aquaculture.

The groups’ letter said there was a move to amend FAO 197-1 in the form of FAO 198-2.

“From the initial copy that we got, we found it to be all about fishponds or other aquaculture and nothing in the provisions are friendly to, or supportive of, mangroves,” said Jurgenne Primavera, chief mangrove scientific adviser of Zoological Society of London and a signatory to the letter.

“The attempt to include mangrove-friendly aquaculture failed in defining the metrics to ensure the survival and growth of these intertidal trees,” Primavera said.

Primavera added that the groups were also asking the BFAR to delete Section 2 on leases and permits “because there are no more available areas for fishpond development.”

According to 2003 data from BFAR, there are around 994 hectares of licensed and unlicensed fishponds that had been reverted to DENR jurisdiction. BFAR records identified 55 hectares of unlicensed fishponds.

Pimavera said there was a need to inventory all abandoned fishponds, FLAs and other aquaculture ponds and establish guidelines to identify abandoned fishponds.

She said BFAR and DENR should reassess the grant of FLAs to financial institutions and study the effects of turning abandoned ponds into salt farms, among other uses.

A ‘win-win nature-based solution’

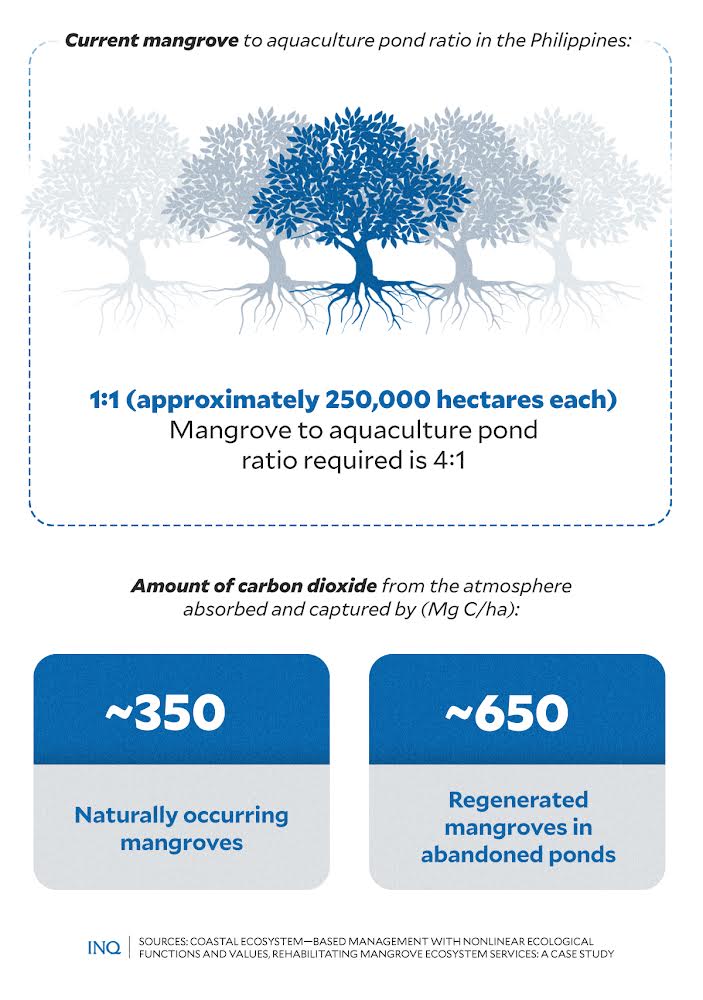

The return of abandoned fishponds to use as mangrove would help achieve the ideal 4:1 ratio of mangroves to fishpond, Primavera said.

Citing a 2008 study, she said the ratio was crucial in environmental sustainability and optimizing the economic benefits of both mangroves and aquaculture ponds.

Currently, the ratio in the Philippines stands at 1:1, with mangroves and ponds each covering around 250,000 hectares.

The mangroves scientific expert also stressed that carbon sequestration is important as a Climate Change Adaptation and Mitigation (CCAM) measure. A 2016 study revealed that mangroves restored in previously abandoned fishponds are more efficient at capturing carbon, with rates of approximately 650 metric tons per hectare, compared to 350 metric tons per hectare in natural mangroves.

“Why doesn’t DA-BFAR encourage the existing fishponds towards achieving the 4:1 mangrove to pond ratio?” Primavera said.

“The agency should craft and implement guidelines, in close coordination with the DENR, to treat the mangrove portion as a biological asset for blue carbon credit trading,” Primavera said.

“This will attract fishpond owners and operators to conserve, restore and rehabilitate mangroves in their fishpond areas and engage in the lucrative blue carbon market,” she continued.

The organizations emphasized the need for a mutually beneficial, nature-based approach that serves the interests of all current and future stakeholders.

RELATED STORY: Mangroves save lives: Greenbelt zones pushed in PH