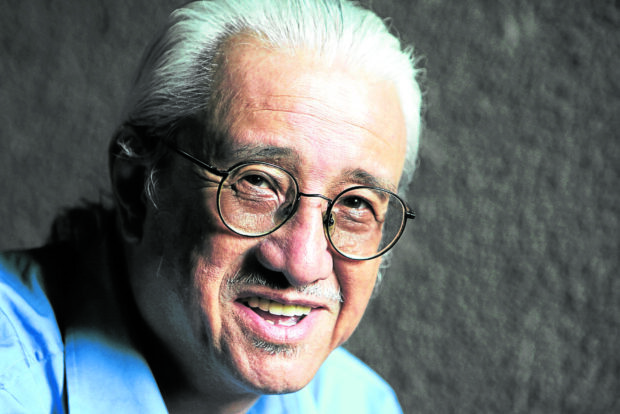

Conrado De Quiros, beloved PDI columnist, author, writes 30

A GAP NEVER FILLED | “A force in the society in which he lived—critical, quite undiplomatic, often opposed to (because unconvinced by) popular opinion,’’ former Inquirer Opinion editor Rosario Garcellano says of the late Conrado de Quiros, one of the paper’s most read. (File photo by JOAN BONDOC)

MANILA, Philippines — His words seethed with fire and ferocity, but the writer himself was a quiet man “who hated bringing attention to himself.”

There’s the rub about Conrado de Quiros, who brandished the pen like a saber, to expose crooks and skewer the wicked, and above all, to keep true to that adage in journalism—to comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable.

And afflict them he did.

De Quiros, whose columns for the Inquirer made him one of the most influential opinion makers of his time, an idol of budding writers and journalists, and a plague on corrupt and depraved officials, has died. He was 72.

“With profound sadness, we announce the passing of our brother, Conrado S. de Quiros. He will be greatly missed by our loving family and friends,” his brother Paul posted on Facebook on Monday night.

Article continues after this advertisementThe wake will be held at the Loyola Memorial Chapels on Commonwealth Avenue in Quezon City from 12 noon on Wednesday until Friday, Paul told the Inquirer.

Article continues after this advertisementDe Quiros’ column called “There’s the Rub” had run in the Inquirer until September 2014 when a stroke forced him to go on a prolonged medical leave.

He began writing his column, whose title was derived from William Shakespeare’s famous “To be, or not to be,” soliloquy in “Hamlet,” in the defunct Philippine Daily Globe in November 1987, before moving to the Inquirer in July 1991.

Defense of Rizal

De Quiros believed that the act of “writing” was no different from and no less than taking “action.”

In one two-part column dated June 18, 2009, he made a spirited defense of the national hero Jose Rizal from detractors who claimed all he had done was to write his essays and novels and become a martyr, while Andres Bonifacio had taken up arms and founded the Katipunan.

“Looking back, you see how wrong that judgment was,” he wrote. “Looking back, you see how the Spanish authorities knew something the activists of my time did not.

Namely, that by writing his essays and his novels, Rizal had become more subversive than Bonifacio or any of the Katipuneros.”

“By writing his essays and novels—and doing so better than Marcelo del Pilar and the other propagandists in Spain—he had done more than those who took up arms,” he added.

De Quiros might well have been standing up for his own work and legacy.

According to former Inquirer Opinion editor Jorge V. Aruta, De Quiros had recognized his own power to shape public opinion but never took advantage of it.

“He was the quintessential journalist. He was honest in his personal and professional life, and he was faithful to the truth,” he said of De Quiros.

Once, Aruta recalled, a group of bishops had threatened a boycott of the Inquirer due to the columnist’s supposedly profane language.

De Quiros “only laughed it off,” he said.

Aquino eulogy

For all his influence, De Quiros disliked being in the public view. “In person he was quite reserved and withdrawn. He always hated bringing attention to himself,” Aruta said.

On Aug. 4, 2009, however, De Quiros needed to step into the limelight when he delivered a eulogy for former President Corazon Aquino, who had been a frequent target of his scathing columns until he had an awkward encounter with her daughter.

“I wasn’t an ardent fan of Cory at the beginning, I was an ardent critic,” he said then.

“I came from the ranks of the red rather than the yellow, and looked at the world from the prism of that color. It got so that in one program Kris Aquino invited me to (I don’t know if she remembers this), she took me to task for it. It was an Independence Day show, and during one break, Kris turned to me and said: ‘Why are you so mean to my mom?’” De Quiros recalled.

“I was, to put it mildly, taken aback. It’s not easy finding a clever answer to an accusation like that put with breathtaking candor. I just flashed what I thought would be a disarming smile. I don’t know if it disarmed,” he said.

“What can I say? Maybe I’m just naturally mean. Or maybe I just say what I mean and mean what I say,” De Quiros said.

Such playful puns and word plays characterized De Quiros’ rhetoric and writing: persuasive, emphatic, and often with a “knockout punch” toward the end.

Few Filipino writers wielded such mastery of the English language as De Quiros did, said Aruta.

“He wrote forcefully, masterfully … yet with grace and elegance. Only very few can do it,” he said.

Carlos Conde, a former journalist and now senior researcher for the New York-based Human Rights Watch, described De Quiros as the “best Filipino opinion writer since the Marcos dictatorship bar none.”

‘Quite undiplomatic’

“His beautifully written and masterfully argued columns, often laden with a fierce moral outrage the times required, helped shape Philippine politics in ways no other columnist did,” Conde wrote.

De Quiros “was a force in the society in which he lived — critical, quite undiplomatic, often opposed to (because unconvinced by) popular opinion,” said Rosario Garcellano, also a former Inquirer Opinion editor.

“Most Tiktok-ers and ‘influencers’ are ignorant of his work. Too bad. The gap left when he was struck by a stroke years ago was never filled,” she said.

Another Inquirer columnist and veteran journalist Ceres Doyo recalled De Quiros’ work to help colleagues behind the scenes.

“Not many know that in 1995 Conrad set up an NGO (nongovernmental organization) called PRESS or Policy Review and Editorial Services to help NGO workers enhance their media literacy and hone their writing and communication skills through seminars and workshops,” she said.

“Grassroots NGOs, he believed, had a wealth of stories that cried out to be told and that engagement with media was empowering for those who needed to be heard,” said Doyo, who was a member of the group’s board.

De Quiros was born in Manila on May 27, 1951, but grew up in Naga City in Camarines Sur.

He made one of his few public appearances after his stroke in August 2015 to join the launch of “Honorary Woman: The Life of Raul S. Roco,” a biography he authored on the late senator from Naga.

De Quiros wrote several other books, among them “Flowers from the Rubble: Essays on Life, Death and Remembering” (1990), “Dance of the Dunces” (1991), “Dead Aim: How Marcos Ambushed Philippine Democracy” (1997), and “Tongues on Fire” (2007).

He won many awards, such as best column from the Catholic Mass Media Awards in 1993, the Rotary Journalism Award in the print category for his commentary on various issues in 1999, and the best opinion piece from the 2003 Society of Publishers in Asia Editorial Excellence Award.

In 2004, he was elevated to the Hall of Fame Award for Opinion Writers by Rotary Club Manila.

Blank column

Inquirer columnist Gideon Lasco said De Quiros would always be known as someone who “fearlessly stood up to presidents and presciently warned against Rodrigo Duterte.”

De Quiros’ June 21, 2011, column was foreboding: “To those in Davao City and elsewhere who say, ‘We don’t mind that Rodrigo Duterte is an SOB so long as he’s our SOB,’ think again. The next time you extol the virtues of a Dirty Harry or a Dirty Rudy, mind that the last dirt you could see could be, like martial law, the one being shoveled up your ass, or face.”

In a thread on X (formerly Twitter), Lasco listed seven of De Quiros’ “memorable pieces” in the Inquirer. One was his Jan. 5, 2004, column, which said a lot with only a title — “A list of the things this country may look forward to over the next six years, from 2004 to 2010, under the administration of President Fernando Poe Jr. and Vice President Noli de Castro.” The entire column, save for the title, had been left blank.

“Silence is more eloquent than words, and imitation is the best form of flattery,” Lasco said, alluding to other columnists who did the same thing on other subjects.

In a Facebook post, former Sen. Francis Pangilinan described De Quiros as an “awe-inspiring, warrior journalist.”

He said he hoped another Conrado de Quiros would emerge from the new generation of journalists, “to carry on as torchbearer of truth and the for-bearer of righteous indignation and purposeful action.”