Martial law survivors: Old is new again under another Marcos

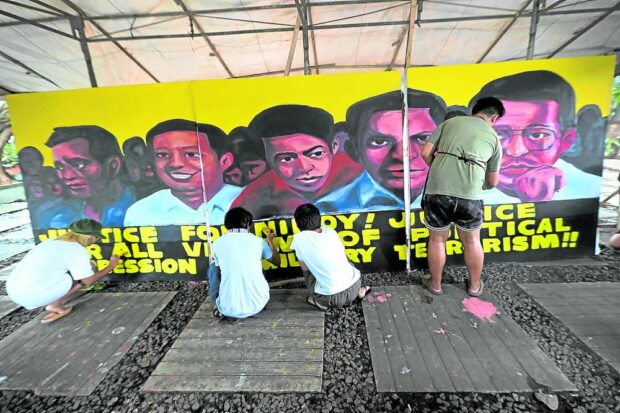

LOOKS PAINFULLY FAMILIAR? At Bantayog ng mga Bayani in Quezon City on Wednesday, artists reproduce the “Justice for Aquino, Justice for All” mural that first hit the restive streets in the 1980s, depicting the slain Sen. Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino Jr., Cordillera leader Macli-ing Dulag, rural doctor Juan “Johnny” Escandor and student activist Edgar Jopson. The new artwork will be a highlight of today’s commemoration of the declaration of martial law on Sept. 21, 1972. —GRIG C. MONTEGRANDE

From the Maharlika fund and Kadiwa stores to the first family’s jet-setting ways, indelible traces of the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos Sr.’s rule are back in fashion under his son’s presidency, activists said on the eve of the country’s commemoration of the 51st anniversary of martial law.

Despite cries of “never again,” it took just one year of President Marcos Jr. in office to undo decades of effort against the excesses and human rights abuses that marked his father’s regime, martial law survivor and activist Judy Taguiwalo said.

This, according to the former social welfare secretary, “was extremely sad but not surprising.”

“It’s not like we achieved what we wanted and then the Marcoses came back,” Taguiwalo told the Inquirer.

“Unless we address the sense of disillusionment of the people and improve our system of governance, Malacañang will always be Marcosian even without a Marcos,” she said.

Article continues after this advertisementThe country observes the anniversary of martial law every Sept. 21 even though Marcos Sr. made the proclamation on Sept. 23, 1972, and antedated it because of superstition.

Article continues after this advertisementOn Thursday, the Campaign Against the Return of the Marcoses to Malacañang (Carmma) and other civil society groups plan to emphasize the parallels between the first and second Marcos governments in the hope that more people would “continue to remember and resist,” according to Taguiwalo.

Martial law museum

Led by Bagong Alyansang Makabayan (Bayan), the groups will meet at Liwasang Bonifacio in Manila at 2 p.m. before marching to Mendiola, near Malacañang.

There they will light candles for the victims of martial law and other rights abuses under both the Marcos Sr. and Marcos Jr. governments.

At the House of Representatives, independent Albay Rep. Edcel Lagman lamented the lack of funding in the proposed 2024 budget for the construction of a museum to remember victims of rights violations during Marcos Sr.’s 21-year rule.

Lagman, whose brother, the labor lawyer Hermon Lagman, was among the disappeared during martial law, said this was despite a “surfeit of funds, including the proceeds from behest loans” granted to cronies of the late dictator.

Under Republic Act No. 10368, or the Human Rights Violations Victims’ Reparation and Recognition Act, the government is mandated to construct a memorial museum, library and compendium honoring the victims.

But the Human Rights Violations Victims’ Memorial Commission’s (HRVVMC) proposed P40.7-million budget for next year is missing any outlay for the proposed “Freedom Memorial Museum” at the University of the Philippines (UP) in Diliman, Quezon City, Lagman noted.

The commission’s budget in 2023 also has no specific item for the museum but there’s a special provision authorizing it to tap a P536-million trust fund.

In August, Commission on Human Rights Chair Richard Palpal-latoc, who also leads HRVVMC, said the construction of the museum would still proceed once the public bidding was done “within the next few months.”

According to activist groups, Thursday’s protest will highlight extrajudicial killings, Red-tagging and abductions of activists, as well as the alleged misuse of public funds for patronage, and the frequent travels of the President and his family.

They will also protest against the implementation of the Maharlika sovereign fund, named after the late dictator’s fictitious guerrilla unit during World War II, as well as the exorbitant confidential funds being sought by various government agencies, including offices of the President and the Vice President.

UP noise barrage

All of these are “legacies of the notorious Bagong Lipunan regime,” said Bayan spokesperson Mong Palatino, referring to Marcos Sr.’s slogan.

“Whatever form of rebranding they’re doing, from ‘Bagong Lipunan’ to ‘Bagong Pilipinas,’ it is clear that changes for the people have not happened and the Marcoses are continuing with the brand of leadership that they had with the martial law,” Taguiwalo said.

UP Diliman, once the bedrock of the student movement against Marcos Sr., also announced a noise barrage and protest on campus.

A memorandum signed by UP president Angelo Jimenez said the protest was part of the university’s “Day of Remembrance” of this “significant day in the country’s history,” but with no explicit mention of martial law.

Economic rights

Taguiwalo, who was detained twice, first in 1973 and then in 1984, and physically and psychologically tortured by state agents, said that from the start, the goal of the antidictatorship movement was not only to oust Marcos Sr. but to advance Filipinos’ civil, political and economic rights, including better wages and health care.

But the administrations after the 1986 Edsa People Power Revolution that toppled Marcos Sr.’s rule all failed to dismantle the “Marcosian institutions” of cronyism, patronage and corruption, she said.

“Many people think that all we want is the remembrance of martial law. But ultimately we want to see people’s lives get better. And we haven’t had that even without Marcos—and that is fertile ground for emergent populist leaders,” Taguiwalo said.

“So now, martial law is back but in a different way.”