More pain, gov’t silence greet kin searching for 2 activists

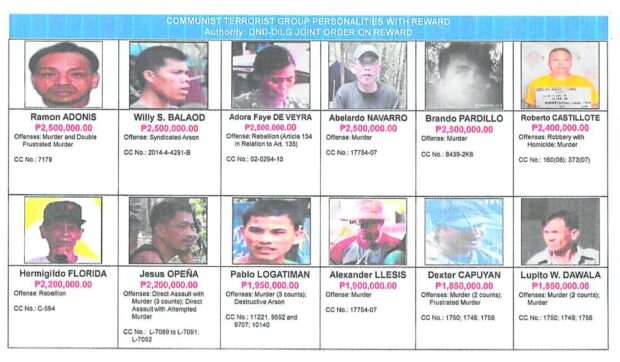

‘WANTED’ The family of Dexter Capuyan, already frustrated in their search for the missing activist, recently made a more troubling discovery: He’s among the suspected communist insurgents “wanted” by the government (bottom row, 2nd photo from right) with a P1.8-million bounty on his head, based on this poster of “terrorist group personalities.” —CONTRIBUTED PHOTO

Nearly two weeks after two Baguio-based activists were reported missing in Taytay, Rizal province, their families and colleagues discovered that one of them had been on a “Wanted” poster released by the Philippine National Police promising rewards for the capture of suspected communist rebels.

The bounty on Dexter Capuyan’s head in particular was P1.8 million.

Capuyan’s family has sought the intervention of the Commission on Human Rights (CHR) to locate the activist or at least piece together how he ended up being a PNP target.

Capuyan, who went missing along with student leader Gene Roz “Bazoo” de Jesus on April 28, landed on a list of 81 wanted people drawn up by the Department of National Defense and the Department of the Interior and Local Government (DILG).

Undated, the list seen by the Capuyan family still includes Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP) founder Jose Maria Sison, who died in the Netherlands in December last year. It also doesn’t explain why Capuyan was facing charges for murder and frustrated murder.

Article continues after this advertisementThe list also included peace talks consultants Leo Velasco (missing since Feb. 19, 2017) and Prudencio Calubid (missing since June 26, 2006), as well as activists already reported to have been arrested, like Evelyn Muñoz, Evangeline Rapanut, Rosita Serrano, Adora Faye de Vera and Eric Jun Casilao.

Article continues after this advertisement“Not knowing Dexter’s whereabouts is extremely hard for us,” Eli Capuyan, Dexter’s younger brother, told reporters on Wednesday. “It’s been two weeks since they went missing, so we are asking the public, who might know where they are, to please help us.”

“To (the activists’) captors, you also have brothers, you also have loved ones. You have no idea of the pain we’re going through right now.”

Before his disappearance, Capuyan, a former editor in chief of Outcrop, the official student publication of University of the Philippines (UP) Baguio, was accused by the military of being a ranking leader of the communist New Peoples’ Army.

‘What is happening?’

De Jesus, a journalism major who graduated cum laude in 2016, once chaired the Council of Leaders at UP Baguio and served as regional convener of the National Union of Students of the Philippines.

His mother, Mercedita, said she was well aware of her son’s organizations, confident that his activities didn’t go beyond advocacy work.

“If I could, I would devote what remains of my life to finding my son,” she said. “I know this is not a simple case of a missing person … And all of us are thinking of the same thing: What is happening to our country? Why are children being separated (this way) from their mothers?”

“I will not shed tears because I know there is hope (that we will) find him,” she added. “Please, please, please, don’t give up looking for him. This is not just about them but about everyone else who has been arrested, killed, disappeared.”

Beverly Longid, spokesperson for the indigenous peoples’ group Katribu and Capuyan’s friend, said that based on initial accounts gathered by the group, De Jesus and Capuyan were taken by unidentified men who arrived in three vehicles and introduced themselves as DILG operatives.

Camp inquiries

Assisted by paralegals, the activists’ families have inquired at Camp Crame and Camp Aguinaldo, and at several military and police installations in Quezon City and the provinces of Rizal and Laguna, to check if they were holding Dexter and Gene.

Longid said the inquiries failed to get answers, as the officers who faced the families declined to accomplish the forms they must fill out as required by Republic Act No. 10353, or the Anti-Enforced or Involuntary Disappearance Act of 2012.

The law requires government agencies, including the PNP and the Armed Forces of the Philippines, to immediately reply in writing to a person or group inquiring about a missing individual.

Dialogue with police

Also on Wednesday, the Capuyan and De Jesus families sought a dialogue with the police and the military in Baguio City and in nearby Benguet province following allegations that the two men were in government custody.

Capuyan’s mother Cynthia, 89, and his aunt, Georgina Gonzalo, 81, were accompanied by their lawyers and human rights advocates when they visited the regional police headquarters at Camp Dangwa in La Trinidad, Benguet, to ask for a certification that the two activists were not in its custody.

In an interview, Cynthia said she was fearing for her and her son’s safety after learning that he and De Jesus could be victims of forced disappearance.

“I couldn’t sleep at night. I wonder if he is eating well. I fear that my son’s captors have killed him,” she said. “What we can do is pray for all of us, for our safety and for guidance in our search.”

Certification

Lawyer Ryan Solano, who was among those who accompanied the relatives, also cited RA 10353, which allows a troubled family to visit military camps and ask officials to certify whether they are holding a missing relative.

The law also calls for the maintenance of an official, up-to-date register of all persons in detention or confinement, in places officially recognized as being built for such purposes.

According to the law, the victims’ families, lawyers, CHR and other parties of interest should have access to the registers.

“What’s difficult here is that we don’t know what happened. We don’t know who is holding them. We will check every military camp to find out if the two are being held there. That’s the only thing we can do for now,” Solano told the Inquirer.

During the dialogue, Police Col. Patrick Joseph Allan, deputy regional director for administration of the Cordillera police, assured the families of assistance in locating the two activists.

Allan also told the families that the regional PNP command would issue a certification after checking all its units in the Cordillera.

RELATED STORY: