PH air pollution eases, but still 3 times higher than what’s safe

MANILA, Philippines—Back in 2020, when COVID-19 lockdowns were still in place, the Philippines saw its air quality improve because of reduced emissions, but as restrictions were lifted, the level of PM2.5, or fine particles, polluting the air is rising again.

This was revealed by IQAir as it released its World Air Quality Report 2022, which found that out of 131 countries and territories, only six met the prescribed annual average PM2.5 concentration of 5 micrograms per cubic meter (μg/m³) or less.

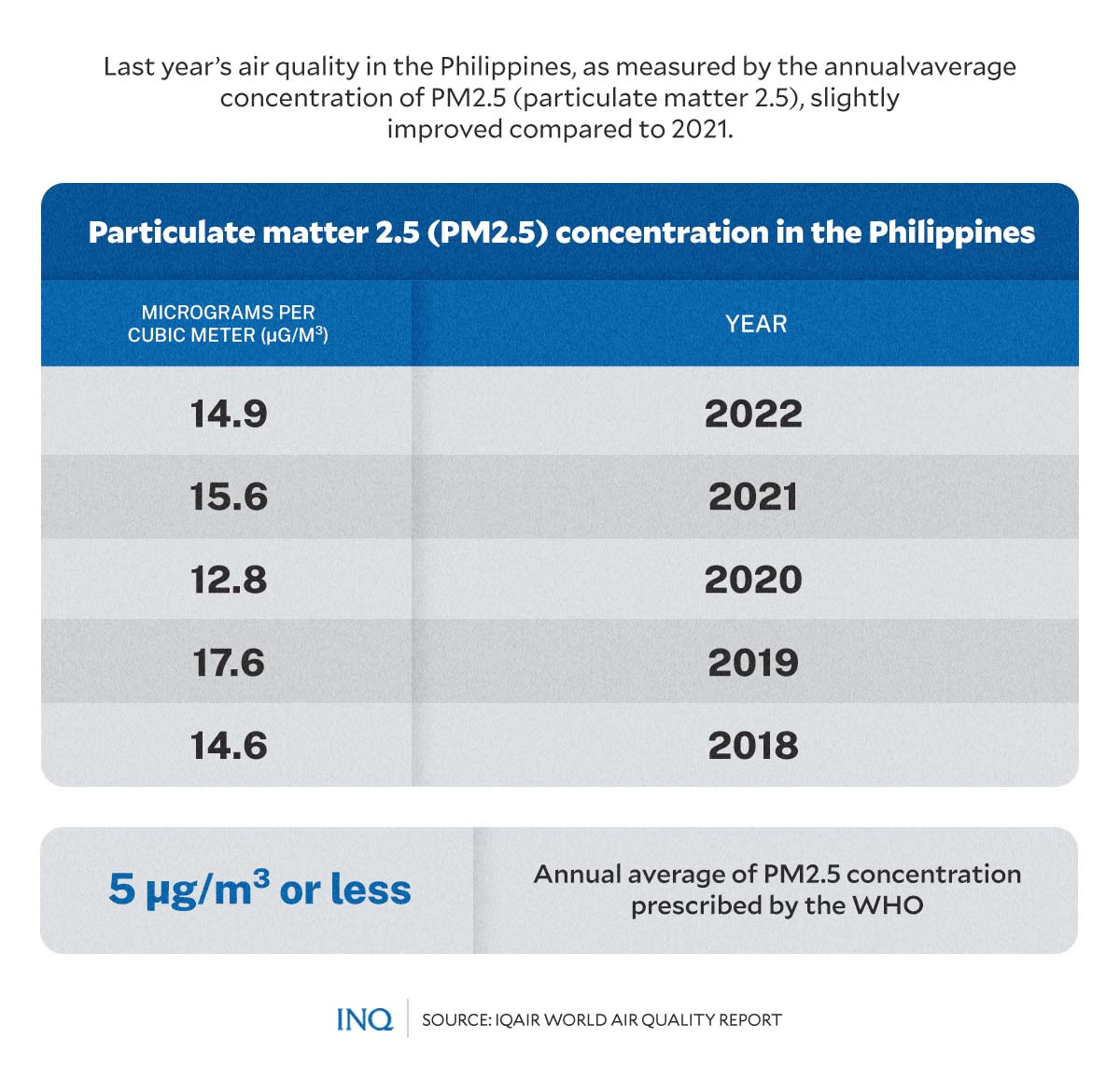

While last year’s air quality in the Philippines, as measured by the annual average concentration of PM2.5, slightly improved to 14.9 μg/m³ from 15.6 μg/m³, it was still three times higher than what is considered safe by the World Health Organization (WHO).

RELATED STORY: ‘Every breath you take’: Air pollution stifles Europe’s health targets

Looking back, PM2.5 concentration in the country was 14.6μg/m³ and 17.6μg/m³ in 2018 and 2019, but with lockdowns imposed to mitigate the spread of COVID-19 in 2020, the level of pollution went down to 12.8 μg/m³.

The report said that with a PM2.5 concentration of 14.9 μg/m³, the Philippines was 69th on the list of most polluted countries and territories last year, an improvement from 64th in 2021.

Chad was the most polluted at 89.7 μg/m³, followed by Iraq at 80.1 μg/m³, Pakistan at 70.9 μg/m³, Bahrain at 66.6 μg/m³, and Bangladesh at 65.8 μg/m³.

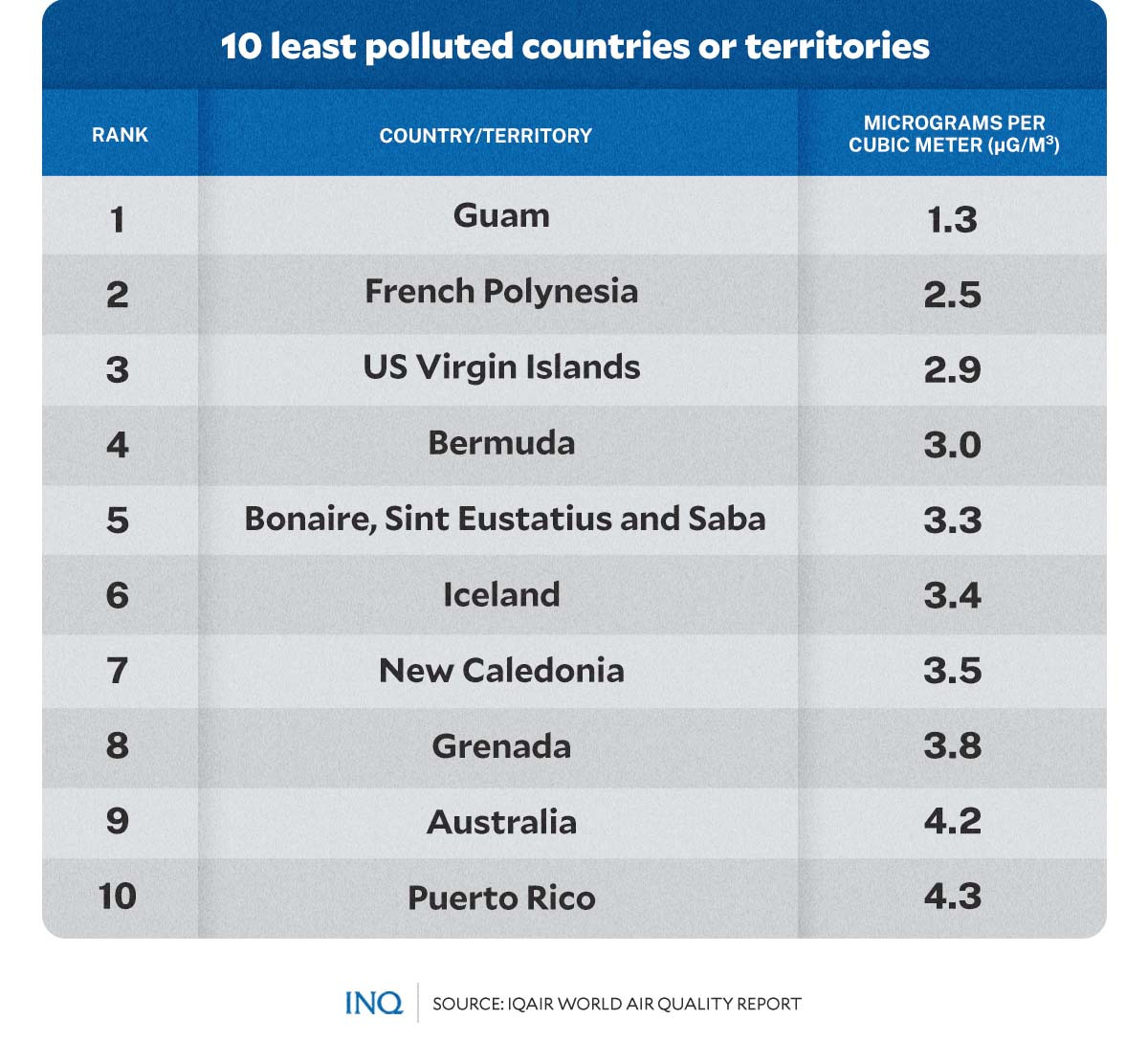

Guam was the least polluted at 1.3μg/m³, followed by French Polynesia at 2.5μg/m³, US Virgin Islands at 2.9μg/m³, Bermuda at 3.0μg/m³, and Bonaire, Sint Eustatius and Saba at 3.3μg/m³.

What’s polluting the air?

Based on what IQAir said, back in 2016, 80 percent of the country’s air pollution was from motor vehicles while the remaining 20 percent was from sources such as factories and open burning of organic matter. The weather is a contributing factor, too.

The Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) stressed last year that the lifting of COVID-19 restrictions worsened air quality in the Philippines, especially Metro Manila.

This, as in 2020, when the government imposed months of hard lockdowns, the country saw road congestion easing and air quality improving, with the University of the Philippines (UP) saying that PM2.5 levels significantly decreased in March that year.

Data from UP’s Institute of Environmental Science and Meteorology indicated that PM2.5 levels fell to 7.1 μg/m³ in the first week of the lockdown, way lower than the 20 μg/m³ recorded two weeks earlier.

As stated by environment journalist Khalid Raji in an article published in the website Earth.org, air pollution in the Philippines likewise stems from the burning of fossil fuels like coal and oil.

“Considering that 53 percent of the population is without access to clean fuels and technology for cooking, this is bound to further exacerbate air quality in the long run,” he said.

Southeast Asia’s air quality

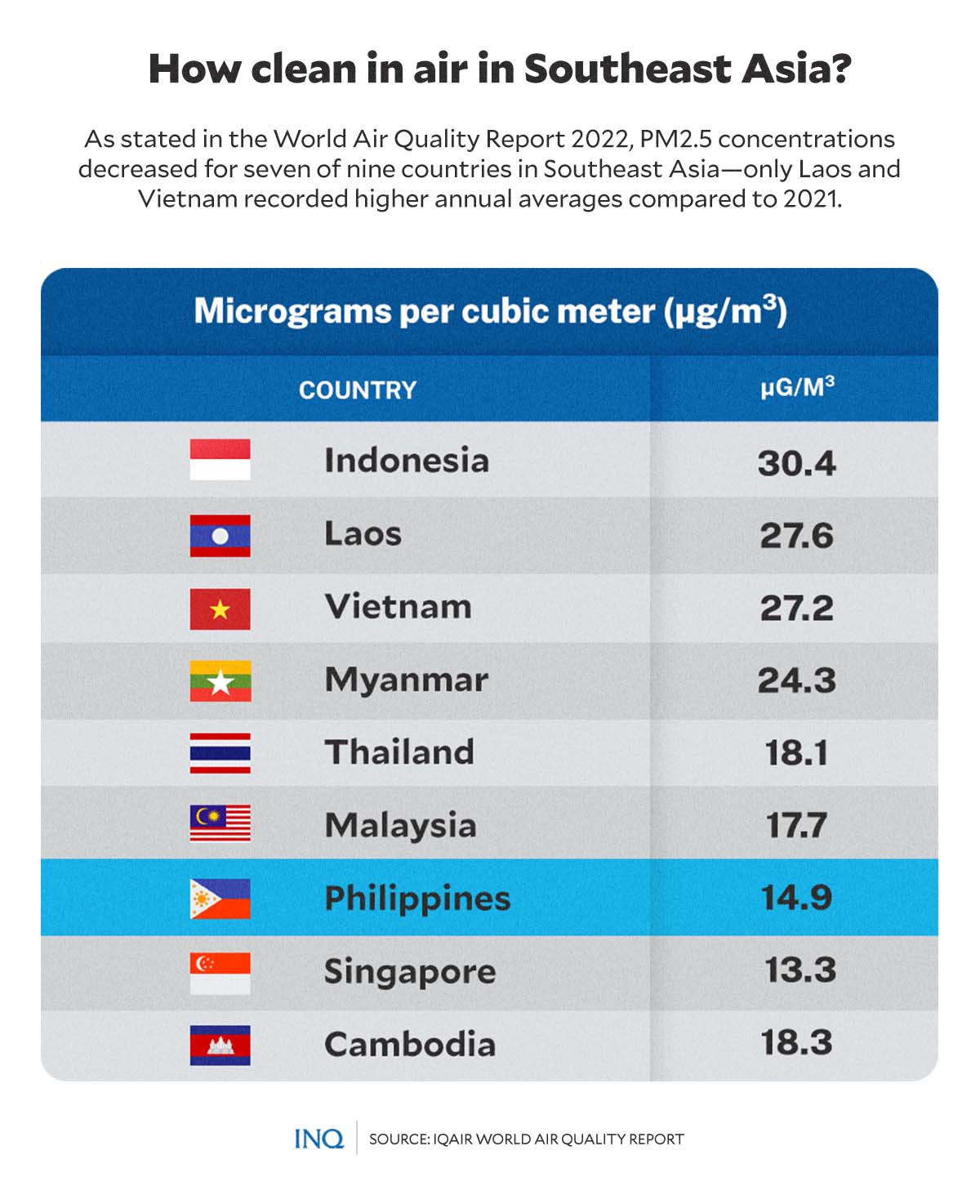

The World Air Quality Report 2022 covered 131 countries and territories, including nine countries in Southeast Asia: Indonesia, Laos, Vietnam, Myanmar, Thailand, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, and Cambodia.

IQAir said countries in the region “have continued their efforts to decrease PM2.5 concentrations to safe levels recommended by the WHO guidelines,” which is 5 μg/m³ or less.

“Industry, power generation, vehicle emissions, and open burning remain top contributors of PM2.5 in the country,” it said.

The Swiss company, which is an expert in air technology, said PM2.5 concentrations decreased for seven of nine countries in the region, and that only Laos and Vietnam recorded higher annual averages compared to 2021.

Indonesia ended the year with the highest PM2.5 concentration of all countries in the region with an annual average of 30.4 μg/m3 . Indonesia was the worst in the region in PM2.5 concentration in 2021 as well.

Cambodia improved its air quality level in 2022 with a 58 percent decrease in its annual average PM2.5 concentration down to 8.3 μg/m3 , the lowest in the region. Cambodia was the 6th most polluted in Southeast Asia in 2021.

IQAir said the region was represented by 296 cities in the World Air Quality Report 2022, but only eight satisfied the WHO PM2.5 guideline limit of 5 μg/m3 , leaving a total of 288 cities that exceeded WHO-recommended PM2.5 concentrations.

Thailand and Indonesia were the most represented on the list of the 15 most polluted cities, with seven and five respectively. Indonesia is also well represented on the list of the 15 least polluted cities with six.

While Vietnam has 7 cities in the list of 15 least polluted cities, its capital city Hanoi was the second most polluted city in the region with an annual average PM2.5 concentration of 40.1 μg/m3.

Fine particulate matter

As stated by IQAir, the data analyzed for the World Air Quality Report 2022 came exclusively from empirically measured PM2.5 data collected from ground level air monitoring stations.

“The PM2.5 measurement data in this report is aggregated from both regulatory air quality monitoring instrumentation and low-cost air quality sensors,” it said.

“Most of the data used in the World Air Quality Report is collected in real-time, with additional supplementary air quality measurements sourced from historical year-end data sets.”

PM2.5 concentration describes the amount of fine particulate aerosol particles up to 2.5 microns in diameter and is used as the standard air quality indicator for the World Air Quality Report.

Measured in μg/m3, PM2.5 is one of six major air pollutants commonly used in the classification of air quality. PM2.5 is largely accepted as the most harmful of these pollutants based on its prevalence in the environment and the wide range of negative human health effects associated with its exposure.

IQAir said PM2.5 can be produced by a variety of sources which can result in different chemical compositions and physical characteristics. Sulfates, nitrates, black carbon, and ammonium are some of the most common particles that make up PM2.5.

The anthropogenic generation of PM2.5 can largely be attributed to combustion engines, power generation, industrial processes, agricultural processes, wood and coal burning, and construction. The most prevalent natural sources of PM2.5 include dust storms, wildfires, and sandstorms.

It said “small particles pose the greatest risk to human health” and that “while the nose can filter most coarse particles, fine and ultrafine particles are inhaled deeper into the lungs where they can be deposited or even pass into the bloodstream.”

READ: Scientists discover how air pollution triggers lung cancer

Here are the measurements, which are in microns in diameter (μm), of some of the particles presented by IQAir:

- Human hair: 50 t0 180 μm

- Sand: 50 to 2,000 μm

- Pollen: 10 to 150 μm

- Mold spores: 8 to 80 μm

- Red blood cell: 7 to 8 μm

- Respiratory droplets: 5 to 10 μm

- Dust: 1 to 1,000 μm

- Bacterium: 0.5 to 10 μm

- Dust mites: 0.2 to 25 μm

- Pet dander: 0.1 to 25 μm

- Coronavirus: 0.1 to 0.5 μm

- Influenza A: 0.06 to 0.12 μm

- Smoke: 0.01 to 10 μm

- SARS-CoV-2: 0.07 to 0.09 μm

Health implications

WHO said air pollutants measured include PM2.5 and PM10 (particles with an aerodynamic diameter of equal or less than 2.5, also called fine, and 10 micrometer respectively), ozone (O3), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), carbon monoxide (CO) and sulfur dioxide (SO2).

PM2.5, it said, can penetrate the lungs and further enter the body through the bloodstream, affecting all major organs and that exposure to PM2.5 can cause harm both to our cardiovascular and respiratory system, provoking, for example stroke, lung cancer and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

New research has also shown an association between prenatal exposure to high levels of air pollution and developmental delay at age three, as well as psychological and behavioral problems later on, including symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, anxiety and depression.

The Indoor Air Hygiene Institute said studies also suggest that long-term exposure to fine particulate matter may be associated with increased rates of chronic bronchitis, reduced lung function and increased mortality from lung cancer and heart disease.

“People with breathing and heart problems, children and the elderly may be particularly sensitive to PM2.5,” the institute said.

This, as exposure to fine particles can also affect lung function and worsen medical conditions such as asthma and heart disease.

“Scientific studies have linked increases in daily PM2.5 exposure with increased respiratory and cardiovascular hospital admissions, emergency department visits and deaths,” the institute’s study said.

Gov’t should act

In 2021, environment groups Greenpeace Philippines and Center for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA) called on the government to speed up efforts to protect Filipinos from the worsening air pollution exacerbated by the country’s dependence on coal.

READ: Pollution costs P4.5 trillion, 66,000 lives every year

They said that as the government focuses on economic recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic, programs to control air pollution must not be sidetracked. These programs include raising stringent standards to control emissions from coal power plants, adding more air quality monitoring stations, investing in low-carbon transport, and transitioning to renewable energy sources.

“The threat of air pollution to human health — and the external costs associated with long-term exposure to it — increases with growing dependence on fossil fuels,” CREA said.

“In addressing this problem, robust monitoring capacity across the country is vital for not only understanding the scale of the health threat to Filipinos, but also ensuring that the right standards and solutions are pursued to control air pollution as quickly as possible,” it said.

For Greenpeace Philippines, the government must first address the outdated air quality standards and the lack of capacity to monitor PM2.5, especially in provinces with coal plants, to ensure that measures to protect Filipinos from health risks are in place.

As stated in the Clean Air Act, the DENR–Environmental Management Bureau is required to conduct a review of standards for stationary sources every two years and revise for further improvement.

“However, the National Emission Standards for Source-Specific Air Pollutants have not been updated since they were set in 1999,” Greenpeace Philippines and CREA said.

“Now more than ever, the government needs to ensure stringent air pollution mitigation because the surge of air pollution that may arise from the reopening of our economy increases our vulnerability to COVID19,” Greenpeace Philippines had said.

READ: World Car-Free Day: A glance at greener, safer roads for people