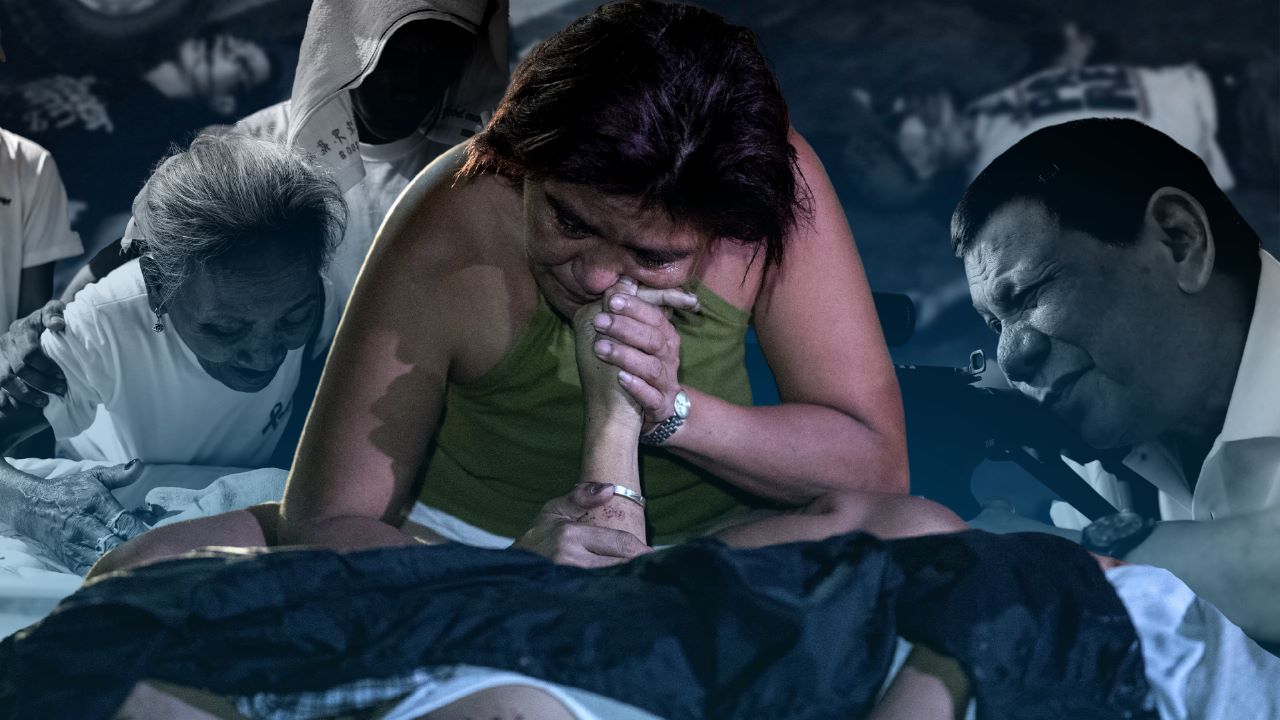

COMPOSITE IMAGE: DANIELLA MARIE AGACER FROM AFP/REUTERS PHOTO

MANILA, Philippines—The government is consistent in its defense against a looming International Criminal Court (ICC) investigation into the previous administration’s bloody campaign against drugs, but for a lawyer representing the victims’ families, the ICC’s intervention is warranted.

Last Monday (March 13), the latest in a string of efforts to halt the possible investigation, the Philippine government officially requested the ICC to reverse its Jan. 26 decision that allowed the resumption of the investigation into the killings, which, based on government data, had claimed 6,248 lives.

READ: Total drug war deaths at 6,248 as of April 30 — PDEA

The ICC Appeals Chamber, in a 50-page document, was asked to “grant suspensive effect pending resolution of this appeal, reverse the ‘authorization pursuant to Article 18 (2) of the Statute to resume the investigation,’ and determine that the Prosecution is not authorized to resume its investigation in the situation in the Republic of the Philippines.”

GRAPHIC Ed Lustan

As state lawyers, including Solicitor General Menardo Guevarra, who previously headed the Department of Justice (DOJ), said, “the ICC prosecution’s activities in furtherance of its investigations would lack any legal foundation and encroach on the sovereignty of the Republic of the Philippines.”

The government gave four “grounds” in its appeal as to why there should be a reversal of the ICC decision on the investigation, but looking back, it has been consistent in what it has been saying since 2018 that the ICC intervention, which victims’ families and lawyers said is a way to hold the responsible to account, will infringe on the country’s sovereignty.

- 7, 2018

Lawyer Salvador Panelo, who was then Malacañang spokesperson and Rodrigo Duterte’s chief presidential legal counsel, said the ICC’s plan to investigate is “an affront to the capability of our courts to act independently, an insult to the Philippine legal system and an infringement upon our sovereignty.”

- 16, 2021

As the ICC said there was “reasonable basis” to proceed with the investigation, stressing that it will look into the crimes allegedly committed from Nov. 1, 2011 to March 16, 2019 in the context of the drug crackdown, Panelo said “this blatant and brazen interference and assault on our sovereignty as an independent country by the ICC is condemnable.”

- 8, 2022

Last year, as the government officially asked the ICC to deny the request of Prosecutor Karim Khan to resume the investigation on the war on drugs after it was suspended on Nov. 18, 2021, Guevarra said “the ICC has no jurisdiction over the situation in the Philippines.”

- 1, 2023

Guevarra reiterated the government’s stand, stressing that “the ICC should respect our criminal justice system, understand its capability and limitations, and not presumptuously impose upon us time limits and procedures that ‘mirror’ its own.”

He said “the role of the ICC is merely complementary, and unless there is a clear showing of unwillingness or inability on the part of Philippine government agencies and courts of law to administer justice, the ICC has no reason, much less authority, to take over the investigation in derogation of our status as a sovereign nation.”

- 18, 2023

Even President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. himself maintained his position: “My position hasn’t changed and I have stated it often even before I took office as President that there are many questions about their jurisdiction and what we in the Philippines regard as an intrusion into our internal matters and a threat to our sovereignty.”

Looking back, however, the ICC, in deciding to authorize the resumption of the investigation, said after a careful analysis of the materials provided to it, it was “not satisfied that the Philippines is undertaking relevant investigations that would warrant a deferral of the court’s investigations on the basis of the complementarity principle.”

RELATED STORY: PH appeals ICC’s revival of ‘drug war’ probe

What’s next?

With the appeal filed by the government, the investigation will hang in the balance since there’s still a possibility that it would be suspended if the ICC appeals chamber will not confirm the authorization to resume the proceedings, in which case the ICC Prosecutor will have to close the investigation.

However, if the ICC appeals chamber will confirm the authorization to investigate, the investigation will continue. But should this be the case, there will still be a problem as “investigations may or may not lead to trials,” New York-based Human Rights Watch (HRW) said.

It explained that “if, based on the investigation, the prosecutor decides to pursue prosecutions, the ICC judges will need to approve the issuance of arrest warrants or summons to appear for individuals on the basis of specific charges.”

GRAPHIC Ed Lustan

“This requires a determination by the judges that there are reasonable grounds to believe that the individual named in the request has committed a crime within the jurisdiction of the court, and either that an arrest is necessary or summons to appear is sufficient to ensure the individual’s appearance before the court,” it said.

HRW said it is difficult to predict how long it might take between the beginning of an investigation and the issuance of arrest warrants or summonses to appear.

It said that in the court’s previous investigations in cases in other countries, the time before any arrest warrants or summonses to appear were issued has ranged from a little less than two months to over six years.

Rough road seen

Once an individual appears before the court, either following an arrest or a summons, the next step is pre-trial proceedings known as “confirmation of charges.” During confirmation-of-charges proceedings, judges determine whether the available evidence establishes “substantial grounds” to believe that the person committed each of the crimes charged in the indictment. If a charge or charges are confirmed, a trial date is set.

RELATED STORY: ‘Kill, kill, kill’: Duterte’s words offer evidence in ICC

But given the statements of officials, both from the present and previous administrations, expressing non-cooperation with the ICC, lawyer Kristina Conti, assisting counsel for Rise Up for Life and for Rights, a group of relatives of those killed in Duterte’s drug crackdown, said the worst case scenario is a possible suspension in the investigation and eventually, trial.

This, as she stressed that in the ICC, rules dictate that the suspect should be in custody because if the suspect is not arrested or does not appear, legal submission can be made, but hearings cannot begin since the Rome Statute explicitly prohibits the use of “trials in absentia.”

As stated by HRW, securing arrests is one of the ICC’s most difficult challenges.

“Without its own police force, the court must rely on states and the international community to assist in arrests. The court has issued arrest warrants against 14 individuals in various countries that have not yet been executed, and some of these warrants are now almost 18 years old,” said HRW.

It said “arrests can take time, particularly where those sought are high-ranking government officials, but usually have occurred with sufficient international support.”

As lawyer Rodel Taton, dean of the Graduate School of Law of San Sebastian College-Recoletos, previously told INQUIRER.net, “the International community is not powerless, it can have individual actions or collective actions just to make a point for rule of law, justice and respect for human rights.”

READ: Hope flickers for victims as ICC to resume investigating Duterte drug war

ICC intervention not a surrender of sovereignty

Contrary to what the government said, Conti said letting the ICC investigate is “not a surrender of territory, not a surrender of functions, not a surrender of authority.”

She told INQUIRER.net that ICC’s jurisdiction was “triggered” because crimes against humanity, which are serious violations committed as part of a large-scale attack on any civilian population, were allegedly committed in the Philippines in the context of the drug war.

Conti, secretary general of the National Union of People’s Lawyers-National Capital Region, said “our participation in the ICC is, in fact, an act of sovereignty,” stressing that the Philippines’ signing of the Rome Statute, which created the ICC, is an act of cooperation with a community of nations to prosecute specific crimes.

These crimes—genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and crime of aggression—she explained, “have historically been excluded from the domestic legal system.” She said these are an “overarching set of crimes” so “what if our legal system is incapable of comprehending these crimes?”, meaning Philippine courts are incapable of handling those.

Back in 2019, the Philippines withdrew from the Rome Statute on the prodding of Duterte, but the Supreme Court (SC) decided in 2021 that the Philippines still has the obligation to cooperate in criminal proceedings of the ICC since “withdrawing from the Rome Statute does not discharge a state party from the obligations it has incurred as a member.”

Killing field

But why did the ICC open an investigation?

As stressed by HRW, “soon after taking office in 2016, Duterte unleashed his ‘war on drugs’, which resulted in thousands of killings, mostly urban poor.”

Based on data from the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency, the total number of people killed in the drug war from July 1, 2016 to April 30, 2022 reached 6,248, but for human rights groups, the death toll could be as high as 30,000, especially when those killed in vigilante-style killings will be included.

Looking at the killings, Drug Archive Philippines, the initiative of a research consortium led by the Ateneo School of Government, De La Salle Philippines, University of the Philippines Diliman and the Stabile Center for Investigative Journalism, introduced a dataset on the deaths.

It stated that based on what it compiled from May 10, 2016 to Sept. 29, 2017, there were 5,021 drug-related deaths all over the Philippines, with Metro Manila having the highest count of victims killed in the context of the drug war—either in police operations or vigilante-style executions.

GRAPHIC Ed Lustan

Exactly 2,000, or 39.8 percent, of all the killings, happened in Metro Manila, followed by Central Luzon (916), Calabarzon (517), Central Visayas (460), Ilocos Region (224), Cagayan Valley (141), Bicol Region (121), Soccsksargen (106), Davao Region (92), Western Visayas (83), Caraga Region (73), Northern Mindanao (70), Eastern Visayas (65), Zamboanga Peninsula (65), Cordillera Administrative Region (44), Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (33), and Mimaropa (11).

With Metro Manila having the most deaths, Drug Archive Philippines said “this is a disproportionate share, considering only 13 percent of the country’s population resides in Metro Manila.”

A closer look at the dataset indicated that in the National Capital Region, the City of Manila had the most deaths at 463, or 23.2 percent, followed by Quezon City (400), Caloocan City (373), Pasig City (156), Pasay City (118), Navotas City (79), Marikina City (60), Mandaluyong City (57), Makati City (52), Taguig City (43), Parañaque City (43), Malabon City (36), Las Piñas City (34), Muntinlupa City (25), Pateros (24), San Juan City (20), and Valenzuela City (17).

Drug Archives Philippines said compared to the rest of the country where most of the deaths are attributable to police operations, the killings in Metro Manila were almost equally split between police operations (49 percent) and non-operations (51 percent).

The scale of the bloody drug campaign prompted then ICC Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda in 2018 to open a preliminary examination of the killings. Years later, after an analysis of the incidents, she requested the ICC’s authorization to open an investigation. Back in September 2021, the pre-trial chamber authorized the opening of the investigation.

‘PH has working legal system’

One of the arguments of the government in asserting that the ICC has no jurisdiction over the Philippines, is that its legal system is working, with the government stressing in its appeal that the ICC pre-trial chamber “erred in its failure to consider all Article 17 factors.”

As stated in Article 17(1) of the Rome Statute, the ICC can rule that a case is inadmissible if “(a) the case is being investigated or prosecuted by a State which has jurisdiction over it, unless the State is unwilling or unable genuinely to carry out the investigation or prosecution.”

The ICC, in Article 17(2), can also rule there is “unwillingness” by a state or country to participate if “(a) the proceedings were or are being undertaken or the national decision was made for the purpose of shielding the person concerned from criminal responsibility for crimes within the jurisdiction of the Court,” including crimes against humanity.

“In order to determine inability in a particular case, the Court shall consider whether, due to a total or substantial collapse or unavailability of its national judicial system, the State is unable to obtain the accused or the necessary evidence and testimony or otherwise unable to carry out its proceedings,” Article 17(3) read.

Conti stressed that “true, we have working courts, open offices, we have an SC that convenes regularly, there is a government that functions, but are the cases related to the drug war being litigated or being brought before the courts?”

GRAPHIC Ed Lustan

She even stressed the implications of how some government officials are defending the previous administration, saying that they should have just said they encourage that everybody possibly involved in the alleged crimes against humanity be investigated.

Recently, some lawmakers from both the Senate and House of Representatives proposed resolutions to defend Duterte against the ICC.

Aside from the ground asserted by the government that the ICC pre-trial chamber“erred in its failure to consider all Article 17 factors,” the 50-page government appeal also stressed that the ICC chamber erred “in law in finding that the Court could exercise its jurisdiction on the basis that the Philippines was a State party ‘at the time of the alleged crimes’ and that the ‘ensuing obligations’ of the Rome Statute remain applicable notwithstanding the Philippines withdrawal from the Statute.”

READ: PH formally asks ICC not to reopen drug war probe

The government also said the ICC chamber made an error in “reversing the Prosecution’s burden of proof in the context of article 18 proceedings” and that the ICC pre-trial chamber “erroneously relied on the admissibility test for a concrete case in the context of an article 18(2) decision.”

How about poor victims?

As stated in Drug Archive Philippines’ report “Building a Dataset of Publicly Available Information on Killings Associated with the Anti Drug Campaign” by David, et. al., while data indicated an occupation, or job, for only a small portion of the total integer of victims, based on their place of residence or their occupation, “it is clear that most of the victims were poor.”

This, as in cases in which the victims’ employment status and occupation were indicated–15.8 percent–it was found that most were in low-paying or skilled work such as tricycle drivers (98), construction workers (32), street vendors (24), jeepney barkers or dispatchers (19), farmers (16), habal-habal and pedicab drivers (15), jeepney drivers (12), and garbage collectors (7). At least 38 victims were reported as jobless.

GRAPHIC Ed Lustan

Likewise, out of the 5,021 drug-related deaths between May 10, 2016 and Sept. 29, 2017, which had been compiled by the Ateneo Policy Center, only a few of those killed were known big time drug dealers.

Some 47 percent were alleged by police to be small-time drug suspects, 23 percent were individuals on watchlists compiled by police and local officials, and 8 percent were alleged by police to be drug users or addicts.

The rest were those alleged to be drug couriers (1 percent), alleged by police to be “narco-politicians” (1 percent), police officers accused of being involved in drugs (1 percent), and alleged by police to be drug lords (less than 1 percent).

Many of the dead were killed at home (24 percent) or their bodies were found on streets or alleys (27 percent). Some nine percent were killed or found dead in a vehicle, based on data from Drug Archive Philippines.