Impunity unbridled: Gov’t targets private armies

COMPOSITE IMAGE BY ED LUSTAN FROM INQUIRER FILE PHOTOS

MANILA, Philippines—The latest in a string of attacks on local executives, the barbaric assault that that killed Negros Oriental Gov. Roel Degamo on March 4 prompted President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. to order the dismantling of “private armies.”

“All the private armies should be dismantled,” he said while stressing that police should also intensify its crackdown on illegal firearms. “If there are few illegal firearms, such kinds of crimes would be few too.”

READ: Marcos orders PNP to identify political hotspots, intensify ops vs illegal guns

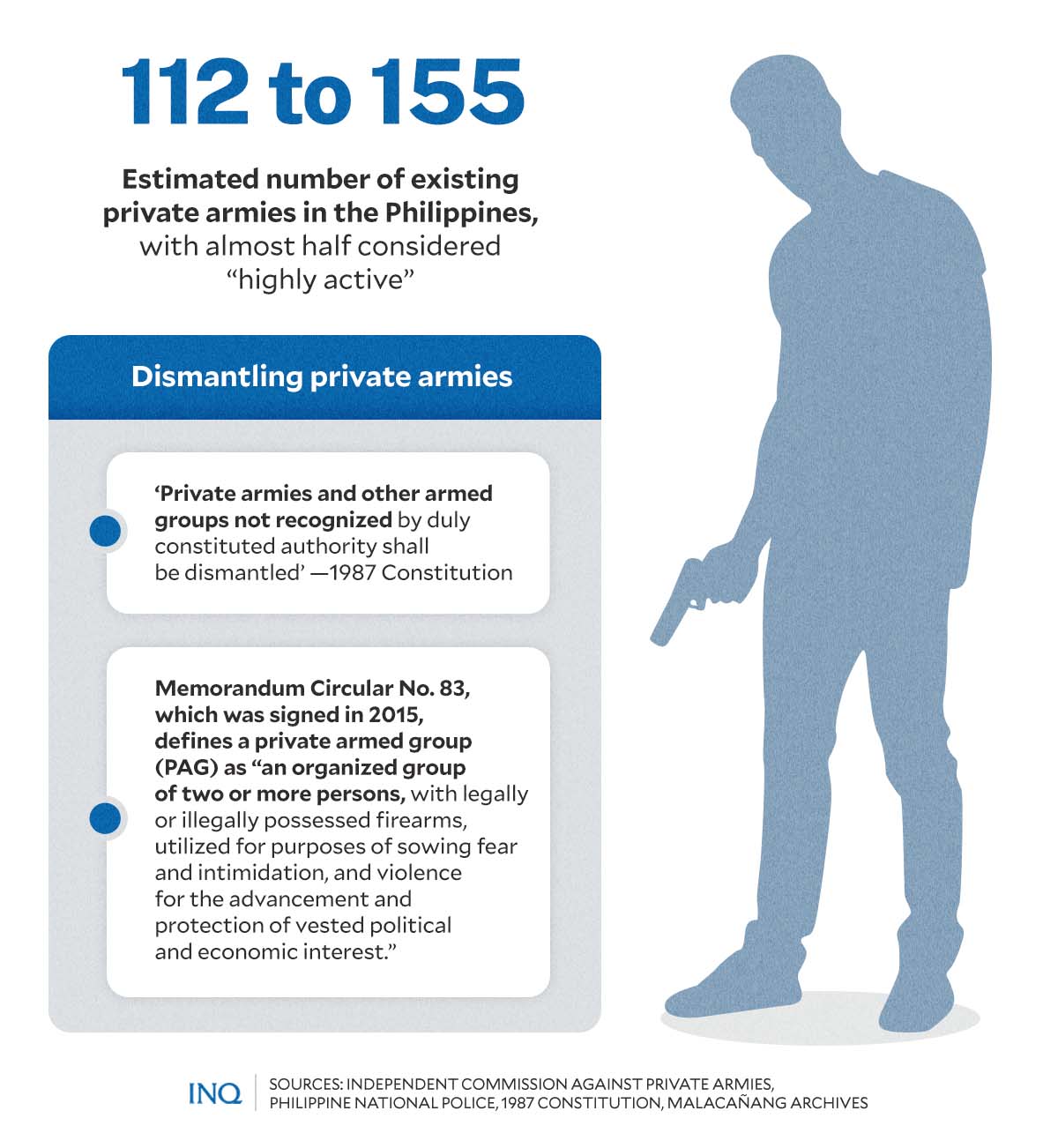

The 1987 Constitution is clear as it provides in Article XVIII, Section 24 that “private armies and other armed groups not recognized by duly constituted authority shall be dismantled.”

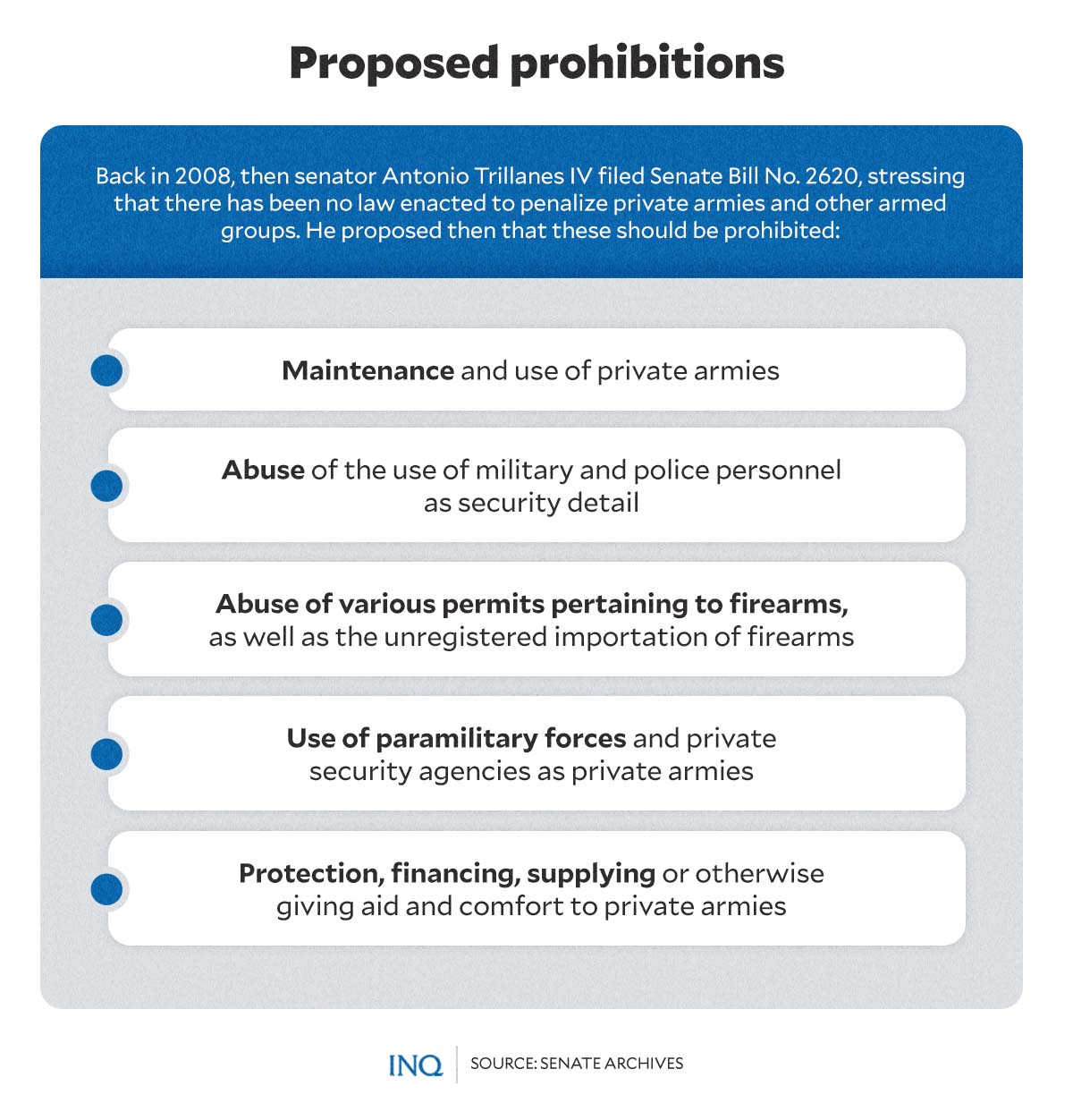

But as stressed in 2008 by then senator Antonio Trillanes, “up until now, no law has been enacted to penalize private armies and other armed groups,” saying that “the culture of fear still prevails.”

This was the reason he filed Senate Bill No. 2620 that year to propose policies addressing the menace of private armies in the Philippines and the laying down of penalties.

Back then, he proposed that these should be prohibited:

- Maintenance and/or use of private armies

- Abuse of the use of the military and police personnel as security details

- Abuse of various permits pertaining to firearms, as well as the unregistered importation of firearms

- Use of paramilitary forces and private security agencies as private armies

- Protection, financing, supplying or giving aid and comfort to private armies

“It is hoped that the enactment of this measure will empower the State to curb and eventually put a halt to the anarchy of abusive government officials and private citizens,” Trillanes had said in his proposal.

As defined by Memorandum Circular No. 83, which was signed in 2015, a private armed group (PAG) “an organized group of two or more persons, with legally or illegally possessed firearms, utilized for purposes of sowing fear and intimidation, and violence for the advancement and protection of vested political and economic interest.”

‘Culture of fear’

Jake Maderazo, a broadcaster, shared in an INQUIRER column that in 1993, there were 558 private armies in the Philippines. However, this declined to 112 in 2010, according to data from the Independent Commission Against Private Armies.

But even if the strength of private armies declined in 2010, the year that then President Benigno Aquino III stressed that the government “does not countenance” such “abhorrence to law enforcement,” the number increased to 155 in 2021.

The Philippine National Police (PNP), as cited by a BenarNews report in 2021, said 155 private armies operate across the Philippines, with almost half considered as “highly active.”

GRAPHIC Ed Lustan

As stressed by then Interior Secretary Eduardo Año, “these gun-wielding thugs continue to strike fear among the innocent, spark vicious clashes with rival clans, or push the agenda of the powerful.”

GRAPHIC Ed Lustan

Based on Senate Bill No. 2620, at least 100 private armies were behind 80 percent of election-related violence in 2001, with a special military unit estimating that these private armies were responsible for 68 of 98 election-related murders that year.

“There have been a number of documented abuses committed by these groups but due to lack of clear-cut government policy guidelines, they have not been curbed, instead, they have remained strong,” Trillanes had said.

Fighting for ‘power’

Maderazo said “with so many powers today given to local government units […] contending families fight for the political and economic control of their jurisdictions, just like before martial law in the 1970’s.”

READ: Congress should ban private armies permanently

He stressed that these feuding families “make them rule like royals with massive influence and employ violent people to keep themselves in power,” with some preferring former military men, often those dishonorably discharged.

“The recent spate of political killings is clear evidence of the continuing and unchecked proliferation of PAGs in this administration,” Maderazo said, referring to private armed groups.

Marcos, however, said the police are still looking into whether the attacks on local executives, including the one that ended the life of Aparri, Cagayan vice mayor Rommel Alameda, are isolated.

READ: Aparri vice mayor, 5 others killed in Nueva Vizcaya ambush

“We are looking and getting all the best intelligence we can from our people on the ground to tell us where [are] the places we should be looking at. Where do we need more people, where do we need more personnel, who are the personalities involved?” he said.

This, as he described the killing of Degamo as “shocking and terrifying,” saying that “perpetrators intruded [in] the governor’s house, and if you can see in the video, they killed everyone who came in their way, even those who are not involved.”

READ: Negros Oriental governor shot dead inside his house

Based on data from the PNP, the death toll from the attack that killed Degamo already reached nine, including individuals who were just receiving 4Ps assistance inside the governor’s residence in Pamplona, Negros Oriental.

READ: Death toll in Negros Oriental shooting rises to 9; 14 others hurt

War on gun-for-hire

Sen. Chiz Escudero, who had echoed condemnation of the attacks on local executives especially Degamo, said the government should wage a war on gun-for-hire syndicates in the Philippines.

He said only the identification and dismantling of groups of hired killers can stop assassinations, stressing that “if these perpetrators have pending warrants of arrest and they are armed and dangerous, then that listing could be an order of battle.”

“Killings eventually become a revolving door phenomenon if we do not neutralize the actors now and in the long run, fix the kinks in our justice system,” Escudero said last March 6.

Dr. Peter Kreuzer said in a 2022 Peace Research Institute Frankfurt (PRIF) report that of 927 cases of killings of barangay and municipal officials, most are carried out by “contract killers.”

“The principals ordering the killings are not investigated, remain in the shadows and enjoy almost complete impunity. As a result, in the vast majority of cases it cannot be proven who actually ordered the killings,” he said.

Kreuzer stated in the report “Killing Politicians in the Philippines: Who, Where, When, and Why” that with violence intensifying over time, there are now 100 politicians being killed every year in the Philippines.

The overall rise in deadly violence against politicians gained significant momentum when Rodrigo Duterte was president—2016 to 2022—when the average deadly attacks rose to a “staggering” 90.2 killings every year.

Looking back, the average was only 43.75 killings yearly in the last four years of the presidency of Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo, and 54.34 killings yearly in Aquino III’s six-year presidency.