Hybrid seeds: The risks farmers are not willing to take

MANILA, Philippines — While the Department of Agriculture (DA) is “optimistic” that the use of hybrid seeds instead of inbred seeds in more than a million hectares of land will increase crop production, some farmers stressed that they won’t take the risk.

The DA and local government units said the use of hybrid seeds has given 41 percent better yield in the past two years, with farmers saying they have harvested 7 to 15 metric tons per hectare compared to the average 3.6 metric tons per hectare for inbred seeds.

This is consistent with what the Philippine Rice Research Institute (PhilRice) said in 2012—that dry season and wet season yields from hybrid seeds are higher by over 1 metric ton per hectare and 0.81 metric ton per hectare.

But even with this, PhilRice stressed in 2017 that it is not easy for farmers to take the risk since there are two main reasons for their indecision to plant hybrid seeds—the lack of irrigation and higher cost of production.

READ: Gov’t told to produce hybrid seeds to control costs

As Joemel Alog, a farmer in Nueva Ecija, said, there are a lot of things to consider: “Do we, farmers, have all the resources to meet what hybrid seeds need to have a better yield? We also need to consider the climate, the land, and if there is enough water.”

Hybrid seeds are from two different cross-pollinated superior plants, making them perform better, especially on nutrient absorption and resistance to pests and diseases. Certified seeds, meanwhile, are made by seed growers from registered seeds.

Since hybrid seeds perform better, PhilRice said production of palay from hybrids is more expensive than those from inbred seeds “because it requires more inputs and needs extra care.”

Production cost ‘too high’

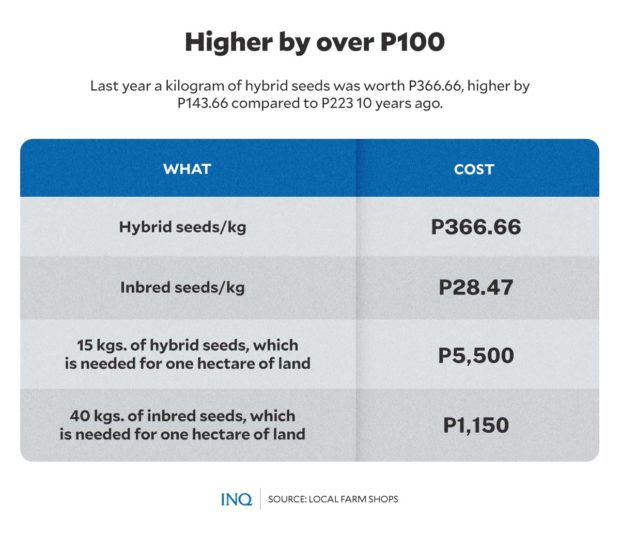

Based on data from PhilRice, a kilogram of hybrid seeds in 2012 was worth P223, while high-quality seeds (HQS) and low-quality seeds (LQS) were P28 and P17 per kilogram.

Then in 2022, as told by a local farm supply shop to INQUIRER.net, a kilogram of hybrid seeds was worth P366.66, still way costlier than inbred seeds, which was only P28.75 per kilogram.

With this, farmers using hybrid seeds need P5,500 to buy 15 kilograms of hybrid seeds, which he or she can plant in one hectare of land. Those using inbred seeds, meanwhile, only need P1,150 for 40 kilograms.

PhilRice explained that palay produced from hybrid seeds “are not for re-planting because of resulting lower yields. Farmers need to buy fresh hybrid seeds every season.”

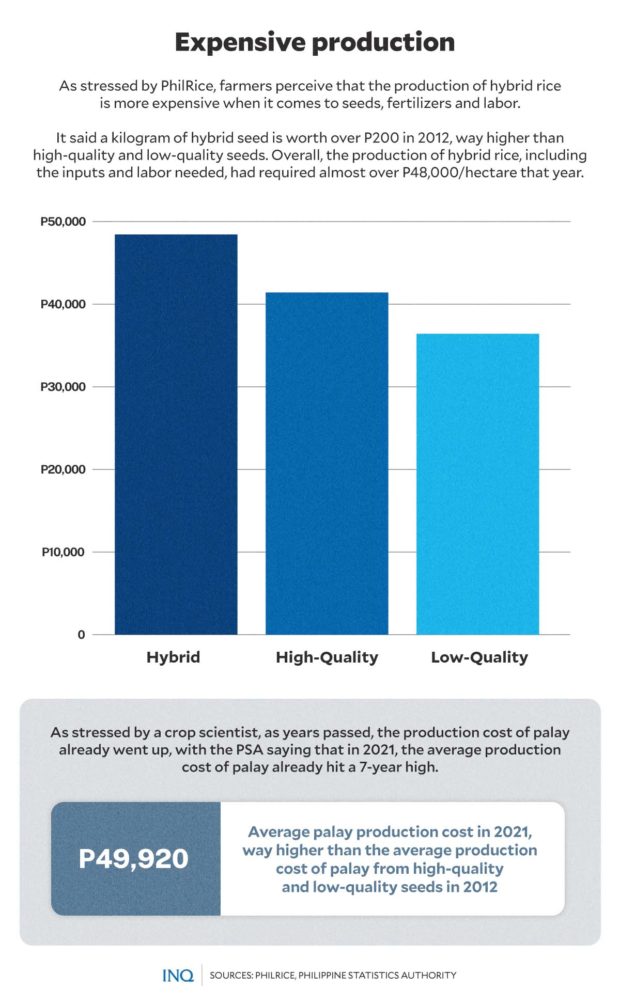

Add to this are the other expenses in the entire cropping season—fertilizers, pesticides, hired labor, and land—which were worth P43,771 for hybrid seeds; P39,098 for high quality seeds and P34,565 for low quality seeds.

This was in 2012, though.

As stressed by Dr. Teodoro Mendoza, a retired crop science professor at the University of the Philippines Los Baños, the production cost of palay has become higher as years passed.

Based on data from the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA), the average production cost of palay hit a seven-year high in 2021: P49,920 per hectare, higher than the P47,027 per hectare in 2020.

Risky

PhilRice, however, stressed that while the production of palay from hybrid seeds is costlier than palay from inbred seeds, “unit cost [for rice produced from hybrid seeds] is lower because high yield compensates [for] the higher production cost.”

Results of the 2011 to 2012 Rice-Based Farm Household Survey, showed that dry season yields from hybrid seeds were higher at 5.8 metric tons per hectare compared to 4.5 metric tons per hectare for HQS and LQS’ 3.7 metric tons per hectare.

Then in the wet season, yields from hybrid seeds were also higher at 4.7 metric tons per hectare compared to HQS and LQS’ 3.9 metric tons per hectare and 3.4 metric tons per hectare.

Even Mendoza said yield from hybrid seeds is 20 to 30 percent higher than certified seeds, stressing that hybridization is accepted all over the world because of heterosis, where hybrids formed are more “robust or vigorous” than their parents.

But as PhilRice said, “Filipino farmers generally don’t take risks.”

Lauro Diego, a farmer-leader of the Magsasaka at Siyentipiko para sa Pag-unlad ng Agrikultura (Masipag), told INQUIRER.net that planting hybrid seeds does not necessarily mean higher yield.

“Not all hybrid varieties are adaptive to wherever they are planted. I already encountered instances where farmers had losses after planting hybrid seeds that did not produce the expected ‘high’ yield.”

As a result, he said, “they were not able to recover the production cost.”

Fill gaps first

PhilRice itself recognized two main factors that impact farmers’ decision to plant hybrid seeds, even saying that the government should expand irrigation systems and devise ways to lessen the cost of hybrid seeds.

“This is true,” Romeo Lomague, a farmer in Pangasinan, said.

“Without adequate water, what will happen to us, farmers, with non-irrigated lands? We will be disadvantaged if we will only rely on rainwater,” Lomague told INQUIRER.net. “We will be miserable.”

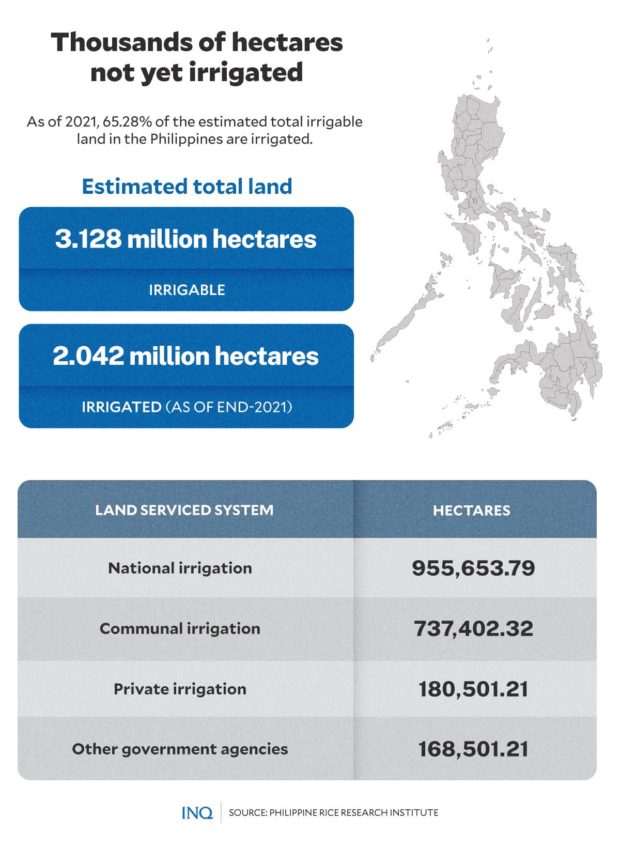

Based on data from the National Irrigation Administration, as of end 2021, 2.042 million hectares, or 65.28 percent of the 3.128 million hectares of estimated total irrigable area in the Philippines, are now irrigated.

It said 955,653.79 hectares are serviced by the national irrigation system, while 737,402.32 hectares are serviced by communal irrigation system; 180,501.21 hectares by private irrigation system; and 168,501.21 hectares by other government agencies.

PhilRice had said “to motivate farmers to plant hybrid rice, irrigation must be provided for them to make their areas ideal for hybrid rice production [since] availability of sufficient water motivates farmers to plant hybrid seeds.”

Last week, as the government decided to promote the use of hybrid seeds, President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. said he will implement the program by providing subsidies and facilitating loan financing to farmers.

The DA, which is still being led by Marcos, said it is now looking at expanding production in Western Visayas, Eastern Visayas, Soccsksargen and the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao.

“The Ilocos [Region], Cagayan Valley and Central Luzon regions have already adopted the hybrid rice technology,” the DA said as it expressed plans to also launch a financial and credit program that will persuade farmers to shift to producing hybrid palay.

As Melchor Panti, a farmer in Bulacan, told INQUIRER.net, “we can plant hybrid seeds, but the government should provide us enough water through the irrigation system and strive to lessen the cost of fertilizers [and pesticides].”

Strategy plan

Last Tuesday (Feb. 14), Marcos met with SL Agritech Corporation (SLAC) chairman and chief executive officer Henry Lim Bon Liong and farmers from Central Luzon to address the challenges in the rice industry.

SLAC—a private firm engaged in the research, development, production, and distribution of hybrid rice seeds and premium quality rice—recommended the conversion of rice farming areas from certified seeds to hybrid seeds.

It proposed to convert 1.90 million hectares of land planted with certified seeds to hybrid seeds in four years, saying that in two croppings every year, hybrid technology will give farmers a chance to earn more income.

READ: DA eyes planting of hybrid seeds in 1.5M hectares of land across PH

Last Friday (Feb. 17), the DA said it is now preparing a “strategy plan” in a bid to increase crop production and eventually achieve rice self-sufficiency in two years as Marcos agreed to the use of hybrid rice varieties.

To reduce the production cost by half and make sure that hybrid seeds are locally adaptive, Mendoza said PhilRice should be the one to produce hybrid seeds. The problem, however, is that it does not have enough resources to produce such.

READ: Marcos approves adoption of hybrid rice to boost crop yield

“That’s why I’m saying that PhilRice should be given more funding and that it should be the one to produce inbred parentals, [which will be used] in producing hybrid seeds to farmers’ cooperatives or associations,” Mendoza said.

RELATED STORY: Villar to DA: Why prefer imported hybrid rice seeds? Not all farmers can use it

High yield could be meaningless

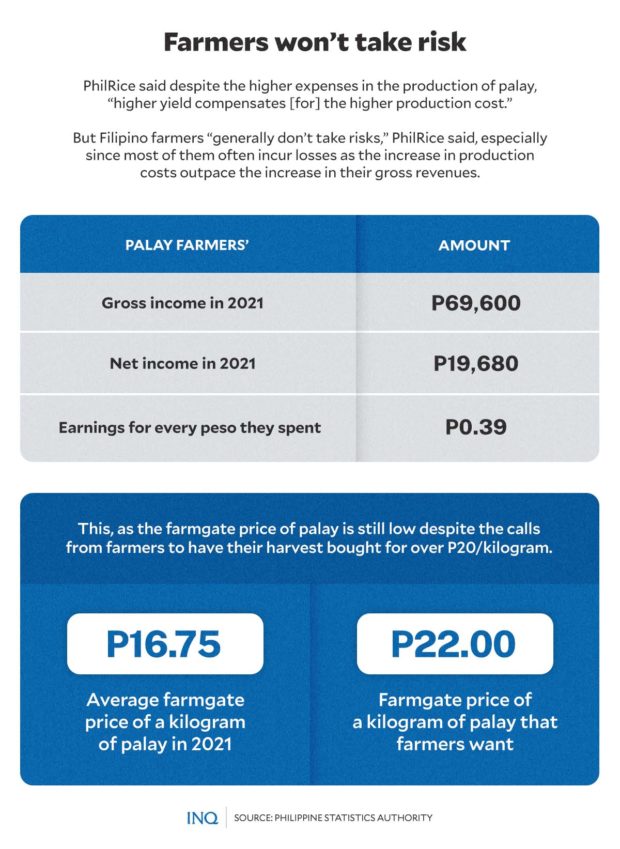

As Diego explained, even if hybrid seeds can produce higher yield compared to inbred seeds, farmers will still be disadvantaged if farm gate prices will still be way lower than what they are calling for, which is P22 per kilogram.

Based on data from PSA, the increase in palay farmers’ production cost made the increase in their gross revenues per hectare meaningless as farmers earned only 39 centavos for every peso they spent in producing the grain.

It said in 2021, palay farmers’ gross income was higher at P69,600. With all the expenses, which increased by 6.15 percent, the net income of farmers declined by 8.43 percent year-on-year to an eight-year low of P19,680 per hectare.

“If the government really wants us, farmers, to produce more yield, it should motivate us by providing assistance and making our call for a P22 per kilogram farm gate price a reality.”

Farmers had blamed the Rice Tariffication Act, or Republic Act No. 11202, as the reason for the declining farm gate prices, with the Federation of Free Farmers saying that farmers have become “net losers” from the law.

Signed on Feb. 14, 2019 by then President Rodrigo Duterte, the law replaced quantitative restrictions—a ceiling on volume—on imported rice with tariffs of 35 to 40 percent.

READ: Imports’ continuing impact on PH farmers: Like dislocating the kneecaps

As stressed by Masipag, “hybridization will do no good in a highly liberalized agriculture where it prioritizes the entry of foreign rice rather than our locally produced rice.”

Hybrid rice ‘a disaster’

The group Masipag said palay produced from hybrid seeds is “a package technology that comes with chemical inputs that are both detrimental to the environment and to the farmers’ already spent pockets as they also need to buy it along with the seeds.”

Dr. Chito Medina, a Masipag scientist, explained that “hybrid rice is highly susceptible to crop failure with its genetic uniformity. If you plant hybrid rice on a wide scale–which the government intends to do—a single fungus or disease can wipe it all.”

Likewise, he said hybrid seeds have low yields unless they are applied with large amounts of fertilizers, and in return they become succulent and susceptible to pests and diseases.

“With hybrid rice being an extremely uniform crop, genetic erosion and possible extinction of our traditional rice varieties that have been ingrained in our centuries-old culture and tradition will most likely be extinct once it is widely cultivated.”

It said in the indigenous communities of Ifugao, local rice varieties such as balitanaw, which has been a key component in the traditional rituals of the Ifugao indigenous community, is now on the brink of extinction.

“[This is] because of the government’s insistence to plant commercial rice varieties created by agro-chemical corporations,” it said.

‘Peasant science needed’

As stressed by Masipag, it is irresponsible for Marcos Jr. and the scientists of SL Agritech Corporations to adapt and plant their hybrid seeds on a nationwide basis.

“It is basic science that in an archipelagic country such as the Philippines, different agro-climatic conditions occur in different areas. A one-size fits all approach such as hybrid seeds is doomed to fail,” Masipag national coordinator, Alfie Pulumbarit, said.

Masipag said the decline in rice varieties, genetic resources, and biodiversity pose risks to a sustainable food system, and to the production of safe, nutritious, and sufficient food.

“While hybrid rice follows the top-down approach to ‘achieve’ food security, Masipag farmers say otherwise,” it said.

“Selection of rice varieties according to the agro-climatic conditions serve as alternatives to chemical-based solutions and laboratory-created technologies such as golden rice and hybrid rice.”

READ: Farmer group slams DA hybrid seed program

“With farmers gradually regaining their lost knowledge erased by top-down solutions pushed by agrochemical corporations, farmers pride themselves as being the primary scientists of their farms and conservers of our local rice biodiversity,” the group said.

It said “we reject hybrid rice and other corporate technologies and we reiterate that in addressing the food security of our country, you must listen to farmers and not to corporations.”

TSB