INQUIRER COMPOSITE IMAGE/JEROME CRISTOBAL

MANILA, Philippines—When Filipino 10-year-olds lack the skill to read and comprehend simple text, what should the government do? Do away with existing programs or fill the gaps?

As stated by the World Bank, children should already have this skill at 10 years old since reading is the gateway to the rest of learning areas, especially mathematics and science.

But in the Philippines, learning poverty hit 91 percent in June 2022, with nine out of 10 Filipino 10-year-olds struggling to read or understand simple text.

READ: WB: 9 out of 10 PH kids age 10 can’t read

The 91 percent is one of the highest in East Asia and Pacific, so President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. said the medium of instruction in schools should be reviewed.

READ: Marcos wants to reexamine medium of instruction in schools

This, as he stressed in his first State of the Nation Address on July 25, 2022 his desire to maintain Filipinos’ command of the English language.

But while it seemed good, especially considering the edge that one will have when he or she speaks the language well, it contradicted a key aspect of the Enhanced Basic Education Act.

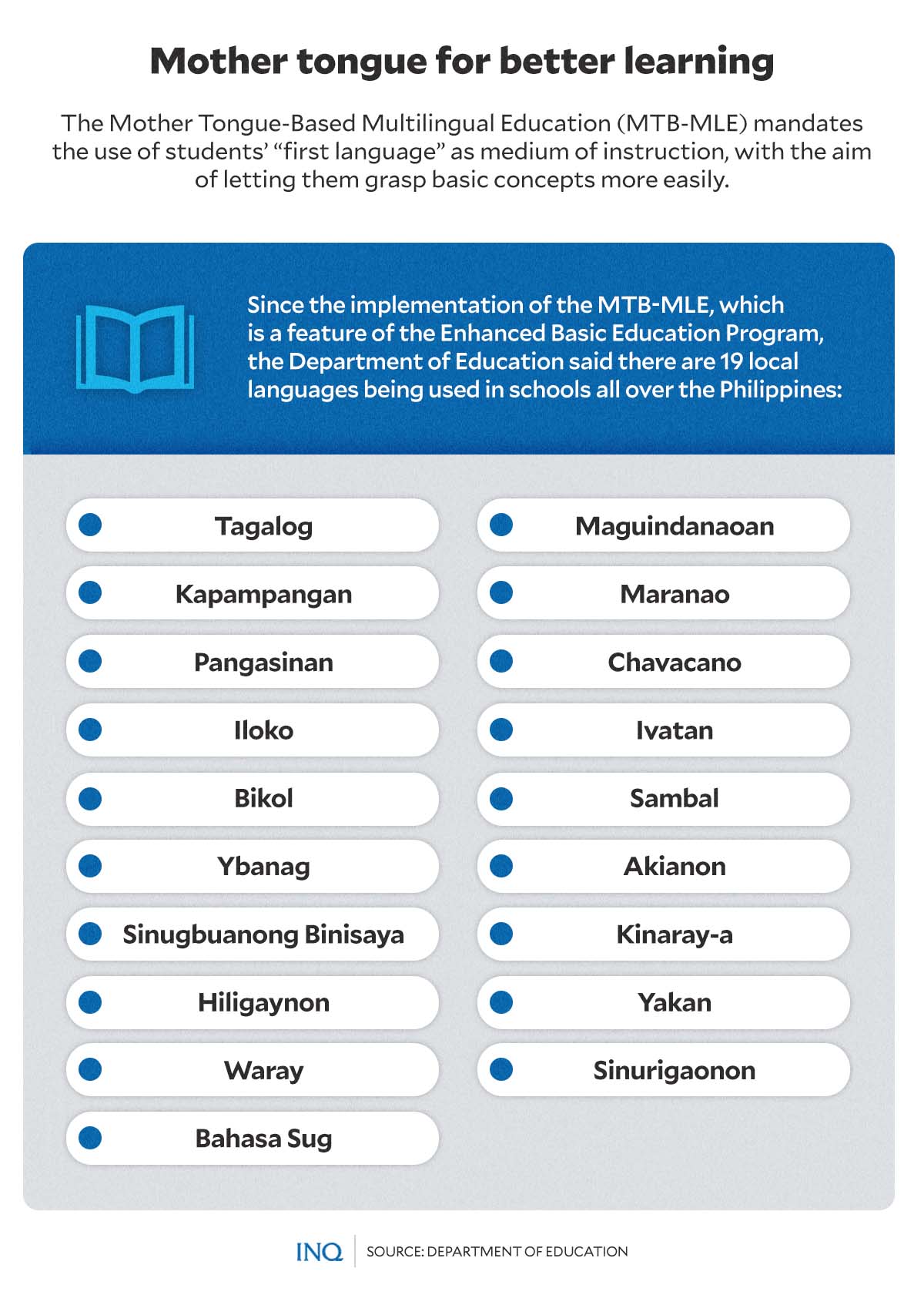

GRAPHIC Ed Lustan

One of the refinements of the K-12 Program, the Mother Tongue-Based Multilingual Education (MTB-MLE) mandated the use of students’ “first language” as medium of instruction.

This, as the Department of Education (DepEd) asserted that learners begin their education in the language they understand best, so the MTB-MLE will help them grasp basic concepts easily.

It was stressed by the department that learners need to develop a “strong foundation in their mother language before effectively learning additional languages.”

“Researchers have proven even in our education with the Thomasites that [a] child’s first language really facilitates learning.”

Weighing gains

As shared in 2016 by Rosalina Villaneza, then chief of DepEd’s Teaching and Learning Division, this gave birth to experiments that yielded “very remarkable” results.

READ: Mother tongue as medium of instruction

The results of the experiments in Iloilo (1948 to 1954 and 1961 to 1964) and Rizal (1960 to 1966) reflected “the value of holistic approach to language in combination with other languages.”

GRAPHIC Ed Lustan

Grades 1 and 2 students in Iloilo were divided into two—the experimental group, who received instructions in Hiligaynon, and the control group, who received instructions in English.

Based on results, students in the experimental group were significantly superior in proficiency in language, reading, arithmetic and social studies than those in the control group.

However, in Rizal, where the teacher training was concentrated in English and Tagalog, students in the all-English group, after completing Grade 6, showed higher levels of proficiency.

Their level of achievement, the DepEd said, was significantly higher than the achievement of students in groups that received instructions in Tagalog.

It was stressed, though, that despite the limitations of training and materials, test results at the end of Grade 4 reflected the “significant strength” of teaching in the local language.

“Receiving instruction in English, the all-English group attained the highest score in language, reading, social studies, health and science, and arithmetic computation.”

“However, for arithmetic problems, the all-Tagalog group (Tagalog medium in Grades 1 to 4) obtained the highest level of achievement.”

GRAPHIC Ed Lustan

The three groups, in the tests’ Tagalog version, had the same proficiency in reading, but it was the all-Tagalog group that had the highest achievement levels in social studies, health and science, and arithmetic tests.

Then in the second experiment in Iloilo, it was found that the literacy rate of the experimental classes in Hiligaynon in 1965 was 75.99 percent, higher than the 1961 level of 53.28 percent.

As stressed by the DepEd, the last experiment indicated that the best medium of instruction to introduce Tagalog and English simultaneously in Grade 1 in Iloilo was Hiligaynon.

“There is reason to believe that, especially at an early age, using the ‘mother tongue’ helps the learning process by introducing concepts to students in the language they are most used to.”

Way to understand concepts easily

So given the findings of the three experiments, the DepEd had inspiration to include the MTB-MLE as a key aspect of the Enhanced Basic Education Act.

Based on DepEd data, there are 19 local languages being used in schools all over the Philippines since the implementation of the program in School Year 2012 to 2013.

GRAPHIC Ed Lustan

These include Tagalog, Kapampangan, Pangasinan, Iloko, Bikol, Ybanag, Sinugbuanong Binisaya, Hiligaynon, Waray, Bahasa Sug, Maguindanaoan, Maranao, and Chavacano.

The MTB-MLE, which is implemented in two modules—as a learning area and as medium of instruction—also uses Ivatan Sambal, Akianon, Kinaray-a, Yakan, and Sinurigaonon.

As a learning area, the program focuses on the development of speaking, reading, and writing from Grades 1 to 3 in the mother tongue.

Then as a medium of instruction, the mother tongue is used in all learning areas from Kinder to Grade 3 except in teaching Filipino and English.

Filipino is introduced in the second quarter of Grade 1 for speaking. For reading and writing purposes, it will be taught beginning in the third quarter of Grade 1.

The rest of the macro skills, which are listening, speaking, reading, and writing in Filipino will continuously be developed from Grades 2 to 6.

“The purpose of a multilingual education program is to develop appropriate cognitive and reasoning skills, enabling children to operate equally in different languages, starting with the first language of the child,” the DepEd said.

Blaming local language instruction

But as early as 2016, the MTB-MLE had been somehow blamed for the declining proficiency of Filipino students in English, something that concerned the President.

This, as in that year, the Test for International Communication’s results indicated that the proficiency of Filipino college students was lower than the target proficiency of Thai high school students.

However, the DepEd defended its program, stressing that the use of mother tongue as medium of instruction is the reason for the decline of the proficiency of students in English.

“Certain studies show that the use of the first language can help students understand what they are reading. The cultivation of the first language also helps students learn additional languages.”

But six years later, the DepEd said it is already reviewing the possibility of removing the mother tongue as a learning area while retaining it as medium of instruction.

Last year, Education Undersecretary Epimaco Densing said the 50-minute mother tongue subject would be replaced by reading and mathematics programs.

He clarified, however, that “we will continue using the ‘mother tongue’ as medium of instruction for students in Kindergarten to Grade 3.”

No more ‘first language’ instructions?

But last year, too, Pasig City Rep. Roman Romulo filed House Bill (HB) No. 2188 in a bid to suspend the use of the mother tongue as medium of instruction for Kindergarten to Grade 3.

So what went wrong?

Last Feb. 6, the substitute bill—HB No. 6717—was already passed by the House of Representatives on final reading as a response to the learning materials written in the local language in schools.

READ: Scrapping MTB-MLE policy will not address learning crisis

Looking back, when the bill was first introduced, Michael San Juan, lead convener of Tanggol Wika, asked congressmen not to suspend the use of the mother tongue.

“The students learn better when they are using our own languages so the use of the mother tongue as the medium of instruction must not be stopped,” he said.

READ: Lawmakers urged to back Filipino as medium of instruction

San Juan had stressed that if there are any problems in the implementation of the MTB-MLE, it must be addressed by giving the program more resources for its improvement.

Even Sen. Win Gatchalian expressed concerns as the Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS) revealed that in 2019, only nine percent of schools are prepared to implement the MTB-MLE.

Based on data shared by Gatchalian, only 1,465 of the 16,287 schools in the Philippines hold four activities needed to implement the program.

The activities are writing big books on language, literature, and culture; documentation of the orthography of the language; documentation of grammar; and documentation of a dictionary of the language.

The PIDS said reasons could be “teachers’ lack of relevant teaching materials, schools’ lack of dictionar[ies] of the language, students’ lack of textbooks, and teachers’ lack of expertise in the school’s medium of instruction.”

As stressed by Gatchalian, “our schools are not ready and our teachers are also not ready because based on DepEd’s information, only 23 percent have been trained and that’s not a good sign also in terms of making sure that the ‘mother tongue’ is successfully implemented on the ground.”

A DepEd assessment indicated that out of the 305,099 personnel targeted for mother tongue training, only 72,872 actually attended.

READ: Gatchalian alarmed most PH schools not ready for mother tongue-based learning

HB No. 6717, once signed into law, would compel the DepEd to work with the Komisyon ng Wikang Filipino in developing teaching materials.

Then its automatic repeal would only take place once the DepEd gives notice to Congress about its readiness to continue the implementation of the program and Congress approves DepEd’s assessment report.

‘Not mother tongue’s fault’

Based on results of a Pulse Asia survey, which was commissioned by Gatchalian, only 38 percent of students said they prefer the local language as medium of instruction.

Filipino was found to be the most preferred at 88 percent, while 71 percent of the 1,200 respondents surveyed last year said they prefer English.

RELATED STORY: Teaching in English may make PH education deteriorate more – ACT

At least 53 percent of respondents in Mindanao and 50 percent in the Visayas said they prefer the mother tongue as medium of instruction, way higher than the 33 percent in Luzon and 18 percent in Metro Manila.

But why?

While it is not clear yet, ACT Teachers Representative France Castro stressed that it was not the use of mother tongue as medium of instruction itself that failed the MTB-MLE.

It’s the government, she said, pointing out that it was the DepEd’s shortcomings and the administration’s dismissal of the need to give the program more resources that is making it hard for the MTB-MLE to achieve its goals.

“The efforts of researchers, educational institutions, and the rest who put their hard work, skills, expertise to develop learning materials will be put to waste,” she said.

“Instead of hanging mother tongue-based learning on the balance, this should be reviewed,” Castro said.

She stressed that “we should pinpoint the root of the problem, listen to the teachers and other education stakeholders, and determine short-term and medium-term solutions.”