Penetrating the silence on a Baguio pioneer’s life

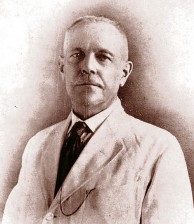

The good-humored Scheerer, 60, said he had to speak out owing to a passion “for all things Otto Scheerer” that he pursued in 1996.

He left without so much as a commitment from the local museum that a correction would be made.

But that occasion does not inspire regrets because the museum episode “is part of the journey,” says Scheerer, who visited the city on a quest to live the life of German expatriate Otto Scheerer—the man history credits for introducing the cattle fields of “Kafagway” to the American colonial government as a suitable site for a sanitarium.

The Americans came, fell in love with the terrain and built Baguio as the country’s summer capital, which turned a century old in 2009.

Although he still teaches biology at the City College of San Francisco, Dr. Scheerer had been spending the rest of his time scouring the Internet for items and conversations that bring him a step closer to understanding his grandfather.

Article continues after this advertisementLinguist

Article continues after this advertisementAll historical references to Otto Scheerer’s life begin in Benguet where he settled before meeting the city’s founding fathers. He was soon appointed Benguet provincial secretary, then governor of Cagayan and later, Batanes. He later began a scholarly investigation of Filipino languages for the University of the Philippines (UP).

Otto Scheerer founded the UP Institute of Linguistics, and his books (“On Baguio’s Past” in 1933 and “The Nabaloi Dialect” in 1905) and papers on Philippine languages have been embraced as definitive sources for scholars.

Dr. Scheerer’s interests, however, is in “penetrating the silence” surrounding Otto’s background.

For example, history provides little context about Otto Scheerer’s past before his adventures in the Philippines, so his grandson plans to fly to Germany in the next few months.

But that’s probably because Otto Scheerer truly believed he had become a Filipino.

Letter to Blumentritt

In a June 5, 1902 letter he sent to Dr. Jose Rizal’s friend, Prague-born teacher Ferdinand Blumentritt, Otto wrote:

“From early 1882 until 1896, I worked as a merchant in Manila. Initially an employee of the trade house E. Kloepfer & Co., I later on did business under my own firm as proprietor of the cigar factory, La Minerva. During these years, I was very fond of using my free time for shorter and longer excursions into the island of Luzon. Having a sufficient knowledge of the Tagalog language, I had the opportunity to get to know the country and its people very well, as those were the days when it was still so easy for a friendly estranjero (stranger) to be admitted to the intimacy of the people.”

“When later, in 1896, my doctor advised me to either return to Germany in order to cure my chronic dysentery or otherwise to prepare for the worst, it was this feeling of being one with the country, which made me move to the mountain district of Benguet together with my two children.

“I knew the pais de Igorrote (land of the Igorrote) because I previously had made two forays into this area to which I eventually owed my complete recovery. It was also in Benguet where I, repeatedly and entirely cut off from Manila, experienced the historic events of the past years, experienced them as a Filipino as I must add.”

Dr. Scheerer says he has a copy of a letter written by a German embassy official, named Kruger, which disparaged Otto as “this hamburger (a play on Otto’s roots in Hamburg, Germany) [who] over time … has become completely indianized,” for criticizing Germany in the “La Independencia.”

“Sometime after [American Admiral George] Dewey left [Manila Bay after defeating the Spanish fleet in 1989], my grandfather noticed German ships [in the region] which made him mad. He did not like imperial Germany,” Dr. Scheerer said.

As a consequence, Kruger “hammered Otto as this man wasting his time living in the mountains married to a local.”

Online copies of the New York Times had ascribed “native” loyalties to Otto Scheerer when he served as Benguet provincial secretary in 1901, a period when Gen. Emilio Aguinaldo was waging his war of independence against the new intruders, the Americans.

Family lore

Dr. Scheerer is also consumed by family lore about which he would not normally write.

He says Japan is his future stop because his grandfather stayed there in the early 1900s where he married the doctor’s grandmother, Toyo Kaiho from Chiba-ken, Japan. Otto’s first wife was Margarita Asuncion, a Filipina.

“I get clues from many people,” says Dr. Scheerer of his quest to learn the life of his grandfather. But the best information, he says, are stories offered by Filipino relatives and friends about the life Otto led in a country where he spent the better years of his life.

Dr. Scheerer opened the new Otto Scheerer Professorial Chair for UP Baguio last week.

But his visit last week made him self-conscious because every step he made reflected fragments of Otto Scheerer’s past.

He is amused that he crossed into the lobby of SM City Baguio on June 15, with no cameras capturing that faintly historic moment. Otto bought parts of Luneta Hill, where the shopping mall now stands, from Ibaloi clan leader Mateo Cariño in 1893, and that’s where he built his thatch-roofed home.