MANILA, Philippines—From 1902 to 1904, cholera, which is a bacterial disease that spreads through contaminated food or water, killed 109,461 people, mostly poor Filipinos who were still reeling from the Philippine-American war.

READ: When cholera and war ravaged PH

As stated by the World Health Organization (WHO), cholera remains a threat to public health all over the world, with researchers estimating that yearly, the disease, which is an indicator of “inequity and lack of social development,” is claiming 21,000 to 143,000 lives.

This was the reason that in 2017, when a cholera outbreak was declared in North Cotabato, WHO stressed that safe water, good sanitation and proper hygiene are critical to preventing cholera infection.

According to data from the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA), confirmed cholera cases fell in 2018, while infections with the bacteria Vibrio cholerae all over the world likewise decreased by 60 percent that year.

This was an “encouraging trend,” WHO said, with its director general, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, stressing that the drop in cases demonstrated an increased engagement in actions to slow and prevent cholera outbreaks.

But years later, Philippe Barboza, head of WHO’s Cholera and Epidemic Diarrheal Diseases section, said the world is seeing a concerning rise in cholera cases this year, with some 26 countries already having an outbreak.

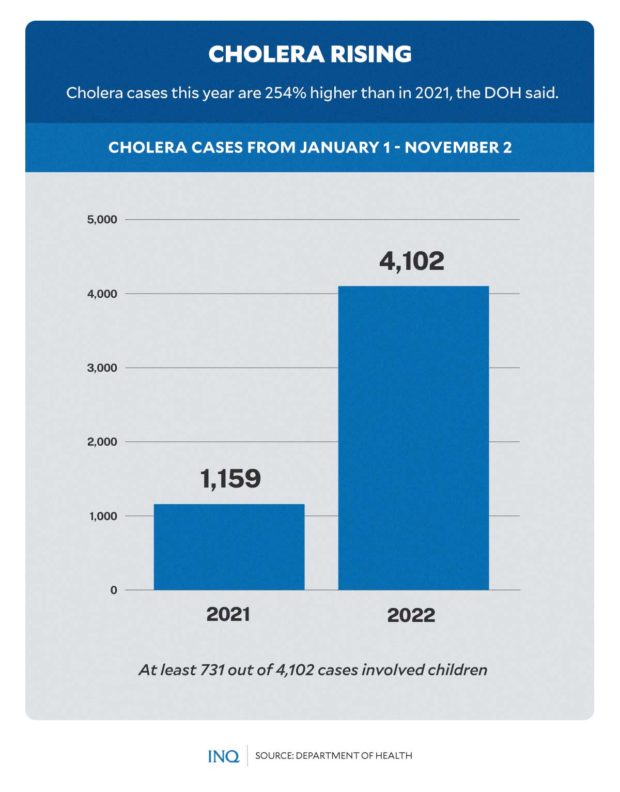

In the Philippines, where the disease once ended thousands of lives, while the Department of Health (DOH) stated that cases are still “manageable,” more people have fallen ill because of cholera this year than in 2021.

This, as the DOH recorded 4,102 cholera cases from Jan. 1 to Nov. 2 this year, a 254 percent increase compared to the same period last year, when only 1,159 infections were recorded.

Out of the 4,102 cholera cases this year, 52 percent or 2,132 are females while 18 percent or 731 are children who are five to nine years old. The DOH said Central Luzon, Western Visayas and Eastern Visayas have reached the epidemic threshold in previous weeks.

As stated by the DOH, 37 people died of cholera from Jan. 1 to Nov. 2—January (1), February (4), March (5), April (5), May (2), June (2), July (3), August (9), September (6).

This, as people with severe cholera can develop severe dehydration, which can lead to kidney failure. If not treated, severe dehydration can lead to shock, comatose and death, the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US CDC) said.

Local outbreaks

According to DOH data, most of the cholera cases from Jan. 1 to Oct. 8, when 3,980 infections were recorded, were from Eastern Visayas (2,678), Davao Region, (441) and Caraga Region (289).

But in a recent period—Sept. 11 to Oct. 8—where 245 cases were recorded, the regions that had the highest number of cases were Eastern Visayas (2,678), Western Visayas (51), and Bicol Region (26).

As stated by the DOH regional office in Eastern Visayas, the cholera outbreak in Tacloban City, which has 426 cases, already resulted in five deaths. It said the 426 infections is higher compared to 192 cases on Oct. 26.

Then in Negros Occidental, the provincial health office said cholera cases increased by 100 in the past two weeks as infections spiked to 24 last Nov. 4 compared to 12 last Oct. 21.

READ: 24 cholera cases logged in Negros Occidental

Talisay City had the most cholera cases with 10, followed by Silay City and the town of Enrique B. Magalona with six cases each, and Victorias City and the town of Calatrava with one case each.

This prompted the Philippine Red Cross to step up aid to residents of that province, providing hygiene promotion lessons to 237 individuals and placing water tankers, bladders, and water purification kits on standby for immediate deployment.

As stated by the DOH’s Epidemiology Bureau (EB), the provinces of Antique, Bataan, Negros Occidental, Northern Samar and the cities of Bacolod Baguio, Zamboanga and Manila had positive growth rate of cholera cases in the past three to four weeks.

‘Prevent, mitigate outbreaks’

Alethea de Guzman, director of the DOH-EB, stressed that “we don’t see a rise in cases as it is currently on a plateau and at the level of the alert and epidemic threshold of cholera cases in the previous weeks.”

However, Sen. Jinggoy Estrada, who filed a resolution last Nov. 2, saw a need for the Senate to investigate, in aid of legislation, the “alarming outbreak of cholera” in several regions.

“More than ascertaining the whys and the wherefores, the situation strongly calls for a review of existing policies to prevent and mitigate the outbreak of the disease,” Estrada said in his proposed Senate Resolution No. 266.

“There is a need to protect the population, especially the children and the underprivileged, against this debilitating yet preventable illness through a coordinated approach among government agencies,” he said.

READ: Lawmaker bats for review, enhanced policies vs choleras amid spike in cases

Estrada said existing policies and programs on sanitation and immunization must be reviewed to enhance emergency response mechanisms and preventive measures against the spread of the disease and to promote public health.

Intensified by climate change

The US CDC said cholera is an acute diarrheal illness caused by infection of the intestine with Vibrio cholerae bacteria. People can get sick when they consume food or water contaminated with the bacteria.

Based on a report by the science news magazine Eos, climate change is predicted to worsen the spread of cholera, with researchers saying that populations all over the world will most likely see “more and more cholera outbreaks.”

As explained by US CDC, infection with cholera is not likely to spread directly from one person to another, so casual contact with an infected person is not a risk factor in becoming ill.

RELATED STORY: Cholera cases 282% higher than in 2021 – DOH

It said a person can get infected with cholera by drinking water or eating food contaminated with the bacteria. The source of contamination is usually the feces of an infected person that contaminates water or food like:

- Tap water supplies

- Ice made from tap water

- Vegetables grown with water contaminated with the bacteria

- Raw or partly cooked fish, seafood from waters polluted with sewage

This was the reason that the disease can spread fast in areas with inadequate treatment of sewage and drinking water, poor sanitation, and inadequate hygiene, placing people living in these areas at highest risk.

READ: Climate change impact: Deadlier diseases

It usually takes two to three days for symptoms to appear after a person is infected with the cholera bacteria, but this can range from a few hours to five days.

US CDC said about one in 10 people with cholera will experience severe symptoms, which, in the early stages, include profuse watery diarrhea, sometimes described as “rice-water stools,” vomiting, thirst, leg cramps, and restlessness or irritability.

READ: Study finds climate change, deadlier diseases go together

Because of profuse watery diarrhea, these signs of dehydration, which can lead to death, should be monitored: rapid heart rate, loss of skin elasticity, dry mucous membranes, and low blood pressure.

Keeping people safe

According to data from WHO, one in 10 people in the Philippines still do not have access to safe water sources, but the government is working to achieve universal coverage for clean water by 2028.

The website water.org stressed that more than three million people in the Philippines still rely on unsafe and unsustainable water sources and seven million lack access to improved sanitation.

“Despite its growing economy, the Philippines faces significant challenges in terms of water and sanitation access. The country is rapidly urbanizing, and its growing cities struggle to provide new residents with adequate water and sanitation services.”

Back in 2020, the United Nations Children’s Fund (Unicef) said the world is alarmingly off-track to deliver sanitation for all by 2030. Sadly, the Philippines is on the same trajectory.

“Implementing the Sustainable Development Goal on sanitation is an investment but inaction brings us even greater costs,” said Dr Rabindra Abeyasinghe, WHO Representative in the Philippines.

“Untreated waste from poor sanitation services has negative effects on the environment and can spread diseases that cause poor health and nutrition, loss of income, decreased productivity and missed educational opportunities,” she said.

To reach the national targets of universal access to sanitation, an average investment of P30 billion per year is needed.

This is 13 percent of the additional internal revenue allotment that local government units will receive by 2022, valued at P225.3 billion per year.

“Let us not wait for another outbreak or pandemic before we prioritize sanitation. The recent typhoons in the Philippines have shown how vulnerable our toilets and the sanitation systems they are connected to are,” said Oyunsaikhan Dendevnorov, Unicef representative.

“This impacts children greatly and will only get worse as the impacts of climate change increase. Achieving universal and sustainable access to safely managed sanitation may be difficult, but it is not impossible.”

“It begins with strong political will at both the national and local government levels to mobilize the investments required, build a larger workforce with better skills, and encourage innovation and data-based decision-making,” he said.