Police visits stir fear in PH, 7th most dangerous place for journalists

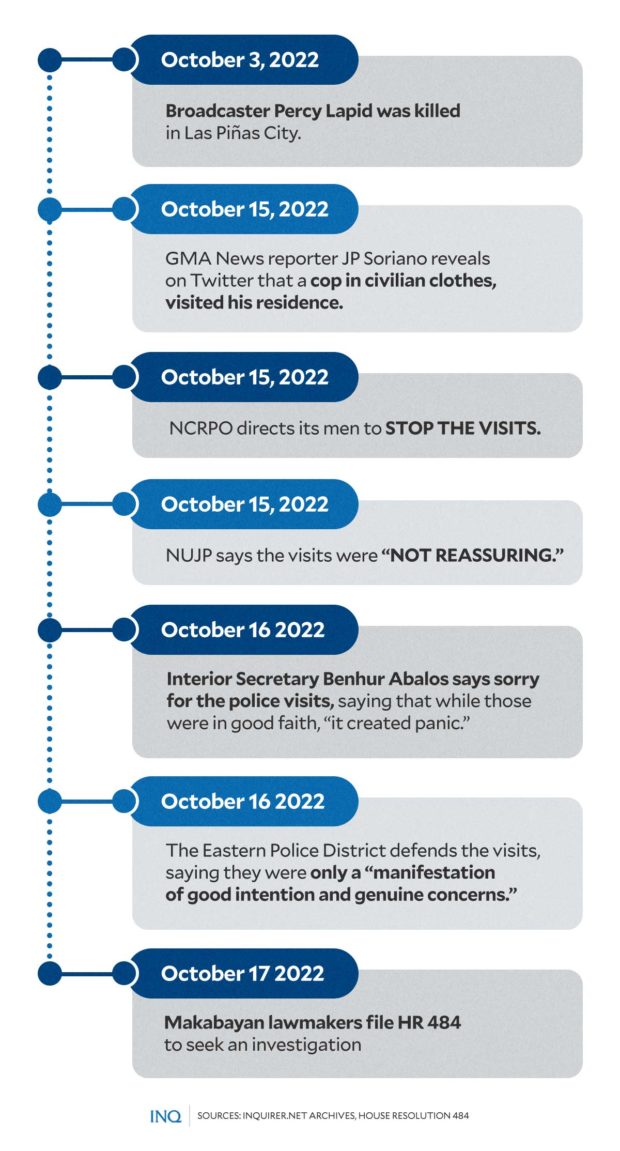

MANILA, Philippines—Percy Lapid, a 63-year-old broadcaster, was killed, and aside from investigating, police “out of good intention and genuine concern” paid a visit to media workers to ask them face-to-face if they had been receiving threats.

The Eastern Police District, which covers the cities of Mandaluyong, Pasig, Marikina and San Juan, said the visit was to ensure the “safety and security” of journalists after the killing of Lapid, the latest in a string of unsolved media killings, in Las Piñas City last Oct. 3.

READ: Eastern Police District defends visits to journalists’ homes

But Len Olea, secretary general of the media organization National Union of Journalists of the Philippines (NUJP), said the timing of the police visits, which were unannounced, “could have never been worse.”

So what went wrong?

Olea stressed that “contrary to the supposed intention of the police, the visits have not calmed journalists down during these disturbing times but have instead caused us anxiety.”

Article continues after this advertisementOlea told INQUIRER.net that it was “utterly wrong for the Philippine National Police (PNP) to conduct ‘surprise visits’ without coordination with newsrooms, press corps or media organizations.”

Article continues after this advertisementShe said in two of the cases, the policemen were not in uniform, a clear violation of the PNP’s standard operating procedures, which states that police operations shall be conducted in this way:

- With a marked police vehicle

- Led by a commissioned police officer

- With personnel in prescribed police uniform or attire

Olea said the NUJP also learned that some of the questions asked were “intrusive.”

One of the media workers visited by police was JP Soriano, a GMA News reporter, who shared on Twitter that a cop in civilian clothes, came to his residence last Oct. 15.

While Soriano made clear that he appreciated the intention of the visit, he questioned why the police officer needed to visit him at his home in Marikina City and why his photo had to be taken.

The case prompted Interior Secretary Benhur Abalos to apologize to the media, stressing in an ABS-CBN News interview that while the police visits were done in good faith, “it created panic.”

While he explained that the police only wanted to ask journalists whether they had been receiving threats, he said the police should have coordinated with newsrooms and media organizations instead of directly visiting them.

Investigate violations

But despite Abalos saying sorry, the Makabayan bloc in the House of Representatives filed House Resolution (HR) 484, which seeks to investigate possible violations committed in the police visits.

Representatives France Castro (ACT Teachers), Arlene Brosas (Gabriela) and Raoul Manuel (Kabataan) were one in saying that they believed that there was a violation of the right to privacy of the journalists, which protects against illegal access to and disclosure and use of their personal information.

They said Section 12 of Republic Act No. 10173, or the Data Privacy Act of 2012, listed conditions that should be met for personal information of any individual to be processed.

Likewise, Section 16 stated that it is the right of the data subject to be informed whether personal information pertaining to him or her shall be, are being or have been processed, the lawmakers stressed in the resolution.

They said “the practice of profiling and granting illegal access to and disclosure and use of the personal information of the people to unauthorized individuals and entities poses fear and threat to their lives and safety.”

HR 484 cited the cases of visits by policemen to the houses of media workers, including Soriano and ABS-CBN reporter Adrian Ayalin, and broadcasters David Oro, Noel Alamar, and Lourdes Escaros. Escaros was visited by police in her work place.

The National Capital Region Police Office already ordered its men to stop the visits, with its acting regional director Brig. Gen. Jonnel Estomo admitting that “this has caused undue alarm and fear.”

READ: NCRPO to cops: Stop visiting homes of journalists in Metro Manila

Protection needed, but respect rights

Indeed, the Philippines needs to make initiatives that would ensure the safety of those in media, especially since it is considered the seventh most dangerous country for journalists, as shown in the Global Impunity Index 2021.

The Committee to Protect Journalists, which released the list last year, said the Philippines still has 13 unsolved murder cases involving media workers. The index covered cases from Sept. 1, 2011 to Aug. 31, 2021.

Based on data from the Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility (CMFR), 281 cases of threats and attacks against journalists in the Philippines were recorded from June 30, 2016 to April 30, 2022.

This consisted of 23 killings; 56 libel cases filed, including online; 55 cases of intimidation; 23 cases of website attack; 23 cases of online harassment, and 20 cases of “barred from coverage.”

The CMFR also recorded 17 cases each of threat by SMS or messaging application and physical harassment or assault; 11 cases of arrest; 10 cases of attempt to kill; and five cases of verbal threat or assault.

The rest of the cases were attacks on media offices—burning of facilities or equipment; strafing or shooting; fake news labeling, cybercrime cases; shutdown; bomb threat; and article takedown.

The Commission on Human Rights (CHR) said it appreciated the police for being “proactive” in ensuring the safety of those in the media, but “home visitation” requires “a careful balance in respecting individual and collective rights.”

It said media security is best pursued through regular coordination with newsrooms, as well as media organizations, to institutionalize efforts in protecting media freedom and safety.

“In this way, members of the media are aware of what to expect and what law enforcement agencies can commit as a means to level off and further improve on protocols as necessary,” the CHR said.

NCRPO spokesman Lt. Col. Dexter Versola had said police welcomed any sanction if the strategy was found to have violated the Data Privacy Act.

Pretext for profiling

Manila Rep. Bienvenido Abante, who is also the chairman of the House Committee on Human Rights, said someone or some people in the PNP should be dismissed or forced to resign over the controversy.

READ: Lawmaker: ‘Axe must fall’ on people involved in police visit to journos homes

He said last Tuesday (Oct. 18) that the police visits violated human rights: “Visiting the media in plain clothes, I don’t think it’s proper. To me, it’s a human rights violation. Very clear. That’s traumatic.”

Castro said she cannot help but recall how police, in the past, had visited some teachers as a pretext in profiling them.

In 2019, an intel memorandum of the Manila Police District ordered its men to “conduct an inventory” of all teachers who are members of the Alliance of Concerned Teachers, an organization that is often a victim of red-tagging.

“After [those house visits], the red-tagging of teachers worsened. In Masbate, whenever [members of ACT held] a meeting, they [would be] visited by the Army who [would] ask so many questions and try to convince them to leave [the organization],” Castro said.

“The problem with these supposed ‘visits’ [is that] they are not mere visits because…they are illegally accessing and/or disclosing and/or using personal information,” said Castro, who is also House minority deputy leader.

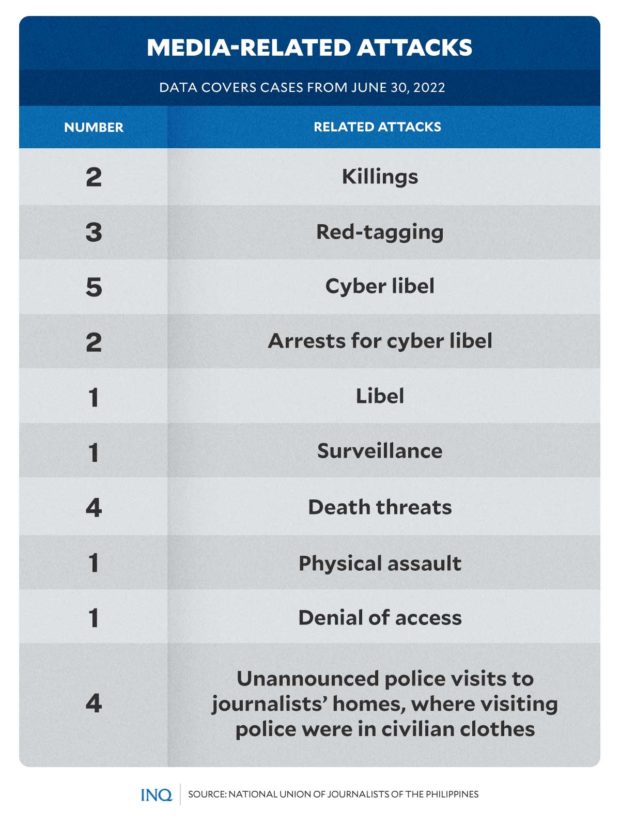

Based on data from NUJP, since June 30, the first day of President Ferdinand Marcos Jr., three journalists had already been red-tagged, while one fell victim to surveillance.

Like ‘Tokhang’

The police visits, Albay Rep. Edcel Lagman said, was reminiscent of the previous administration’s “intrusive and illicit ‘Operation Tokhang’ on drug suspects.”

“These veiled harassments must be stopped as they constitute attempts at prior restraint on the freedom of expression,” he said, stressing that “crusading journalists need police protection from threats and harm, not police intrusion into their privacy.”

For Olea, the PNP should instead “first resolve cases of media killings and other attacks which have been brought to their attention” to promote and protect the safety and rights of journalists.

Based on data from the NUJP, two media workers had been killed since June 30. Likewise, it recorded five cyber libel and one libel cases filed; two arrests over cyber libel; four cases of death threats; one case of physical assault; and one case of denial of access.

“The PNP should uphold press freedom, understand the role of the media in a democracy, and stop red-tagging journalists and media outfits,” she said.