CHEd ends 11-year curb on new nursing courses

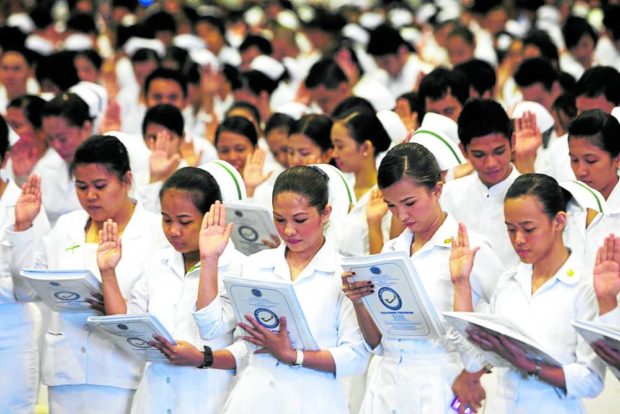

QUALITY GRADS ONLY | While some schools were allowed to continue their nursing courses, these were subjected to strict evaluation by the Commission on Higher Education. (INQUIRER FILE PHOTO)

MANILA, Philippines — The Commission on Higher Education (CHEd) has lifted the 11-year moratorium that barred several higher education institutions (HEIs) from offering new undergraduate and graduate nursing programs.

While some schools were still allowed to continue with their BS Nursing courses, these were subjected to strict monitoring and evaluation based on their compliance with CHEd requirements and the performance of their students in the licensure exams.

The moratorium was imposed in 2011 due to an oversupply of nursing graduates, the declining performance of nursing education graduates in the Nurse Licensure Examinations (NLE); the proliferation of HEIs offering BS Nursing Programs, with some barely reaching the standard passing rate, and students paying hospitals just to be trained due to their schools’ lack of affiliations with base hospitals.

When the ban was declared more than a decade ago, data from the Department of Labor and Employment showed a “massive surplus” of nursing graduates that reached about 280,000, most of whom were either unemployed or underemployed.

The government reviewed the ban after the COVID-19 pandemic exposed the “perceived” lack of health workers in the country, CHEd Chair Prospero De Vera III said at a press conference on Wednesday.

Article continues after this advertisementIn deciding to lift the moratorium, De Vera said CHEd carefully considered the supply and demand of nurses according to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UN SDGs). With its objective of having 27.4 nurses per 10,000 population, a total of 201,265 job positions for nurses must be filled nationwide, representing the huge gap between the UN SDGs ideal number of 300,470 nurses and the actual number of nurses in the Philippines of around 90,205.

Article continues after this advertisementStarting July 14, CHEd said HEIs may submit their applications to open new nursing programs, but noted that it would be strict in considering the applications to ensure the problems encountered before the moratorium would not happen again and at the same time address the lack of licensed nurses in the regions needing more nursing HEIs.

CHEd also defended the timing of the lifting, which several lawmakers and stakeholders said came too late.

De Vera said they had to address issues that caused the moratorium in the first place. “If you immediately lift it, you might go back to the same situation before 2011, and that situation is of crisis proportions at that time,” he said.

Lack of access

De Vera underscored the “unequal” regional distribution of HEIs offering nursing programs, resulting in limited access to nursing courses in some regions.

CHEd’s 2021 data showed that out of the 333 HEIs currently offering nursing programs, only three universities are in Caraga and four in Mimaropa regions, as compared to the 62 HEIs in the National Capital Region.

“Out of 333, there were only 79 public universities offering it and 254 private,” De Vera said.

The commission came up with a data analysis on the regional distribution of HEIs offering nursing programs, taking into account the nurse-to-population ratio, SDG requirement, the total number of base hospitals and available beds for the nursing student’s training program.

Based on the results of the CHEd nursing technical panel’s assessment, the top six regions with an “urgent need” to have nursing programs included Mimaropa ( Mindoro Occidental and Oriental, Marinduque, Romblon and Palawan), Eastern Visayas, Caraga Administrative Region in Mindanao, Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM), Cordillera Administrative Region, and Soccsksargen (South Cotabato, Cotabato, Sultan Kudarat, Sarangani and General Santos City).

The high priority group included Calabarzon (Cavite, Laguna, Batangas, Rizal and Quezon), Western Visayas, Bicol, Davao, Cagayan Valley and Central Luzon.

With the decision to lift the moratorium, De Vera said that from the previous requirement of level 3 hospitals, level 2 DOH-accredited hospitals could now serve as teaching or training institutions for nursing students, provided that they have adequate facilities, caseload for students and minimum capacity of 100 beds with general services.

As part of the lifting of the moratorium, state universities and colleges and local universities and colleges recognized by CHEd were also encouraged to include return-service agreements in their admission and retention policies to help increase the number of nurses per region.

Citing the decline in the quality of graduates, the moratorium imposed by CHEd in 2011 included new course offerings in four other fields of study aside from nursing.

It covered new undergraduate and graduate programs in business administration, teacher education, hotel and restaurant management and information technology, which were some of the more popular college courses.

“There is already a proliferation of higher education institutions offering undergraduate and graduate programs [in these fields] which, if allowed to continue unabated, would result in the deterioration of the quality of graduates of these five higher education programs,” said then CHEd Chair Patricia Licuanan.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) report State of the World’s Nursing 2020, the Philippines has 526,331 nursing personnel, accounting for 71 percent of the country’s health workforce.

The report projected a shortfall of 4.6 million nurses worldwide by 2030.

In the Philippines, the projected shortfall of nurses was expected to be 249,843 by 2030, unless greater investment was made to retain them in the Philippine health sector, it said.

—WITH A REPORT FROM INQUIRER RESEARCH

RELATED STORIES

CHEd to close down more nursing programs in 2013