Baguio’s gains, losses in modern charter

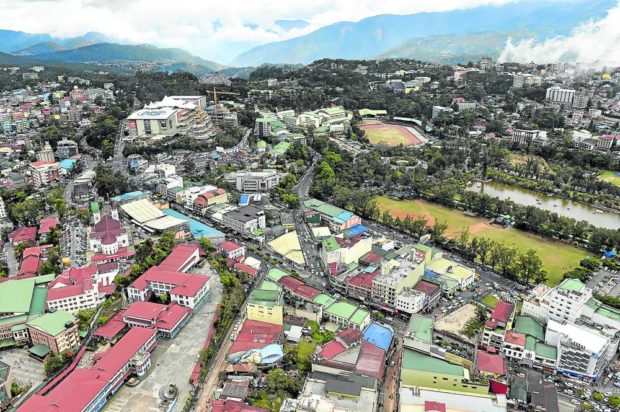

A CENTURY HENCE | Among the country’s cities, Baguio is the only one designed and built as a hill station by the American colonial government in the early 1900s. It was in the summer capital where the members of the Philippine Commission held their first session in 1904. But Baguio’s 1909 colonial charter was updated and replaced only this year, or some 113 years later. —Photo Courtesy of Ompong Tan.

In 1909, a large rock at a bridge over the Irisan River and a bridge over a small creek leading to La Trinidad Valley were marked by the Philippine Commission as part of the boundaries of Baguio City.

Designed and built as a hill station by the American colonial government, Baguio became a chartered city like Manila through Act No. 1963 and was opened for settlement through the sale of townsite lands in order to finance its operations.

By the time Baguio celebrated its centennial in 2009, it had become a multicultural community and a financial center of the Cordillera region. But it took 113 years before Act 1963, the colonial-era law which served as Baguio’s charter, to be replaced with a modern version.

House Bill No. 8882, the new charter, lapsed into law on April 11 and was designated as Republic Act No. 11689. The bill’s author, reelected Baguio Rep. Marquez Go, said the new charter brings the outdated document to the modern world by incorporating current policies and the bureaucracies governing Baguio today.

The new law, for instance, mandates the election of the indigenous peoples mandatory representative to the city council.

Article continues after this advertisementGo said the new charter also references international and progressive concepts, like the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals and climate change.

Article continues after this advertisementAmong the significant highlights of RA 11689 was the exclusion of unoccupied alienable lands “between roads and lands adjoining legal easements from creeks and rivers” from sale. Instead, these lots measuring 200 square meters or less shall be delineated as part of Baguio’s greenbelt, according to Secretary Luzverfeda Pascual, presidential adviser on legislative affairs. She presented the charter to the council on March 7.

But because they believe some of the new charter’s provisions would harm the city, most members of the city council had made last-ditch efforts to convince President Duterte to veto what is essentially Baguio’s new constitution.

NEW BEGINNINGS | Baguio’s Ibaloy community thrived in the fringes when the American colonial government designed and built Baguio City over their cattle lands. More than a century later, these families have become the oldest clans living in what has become a major urban area, and have been honored with their own Ibaloy Day every February. (Photos by RICHARD BALONGLONG

and EV ESPIRITU / Inquirer Northern Luzon)

Division

Nine councilors had voted in favor of a March 21 resolution asking for the veto, and had wanted the document to first be submitted to a plebiscite because of changes that affect future generations.

One sticking point was Article XII of RA 11689 that separates the forested Camp John Hay reservation, now administered by the Bases Conversion and Development Authority (BCDA), from the city townsite. The Camp John Hay property, of which 247 hectares have been commercialized, was the only government reservation to be excluded from the townsite in the modern charter, unlike 15 other military, forest, health and agricultural reservations inside the city borders.

The councilors were concerned that RA 11689 forced Baguio to abdicate its interests in the former American rest and recreation center, among them 19 conditions spelled out in Resolution No. 362 (series of 1994).

Before the BCDA leased the built-up portions of Camp John Hay to a developer, it agreed to abide by these conditions in order to secure the city council’s endorsement of a Club John Hay Master Development Plan.

At stake now is the segregation of 14 barangays (Condition No. 14) that were formed when John Hay was under American military control, the councilors said. Houses in Barangay Scout Barrio were released from BCDA control beginning 2001 although not the roads, parks and other facilities meant for public use. To date, BCDA and a task force led by reelected Mayor Benjamin Magalong have been working on the segregation of the villages of Sta. Scholastica, Baguio Country Club, Upper Dagsian and Greenwater.

Resolution 362 also grants Baguio a 25-percent share from Camp John Hay rentals (Condition No. 10), recognizes the land rights of Baguio Ibaloys (Condition No. 5) which BCDA now seeks to nullify in court, and empowers the Baguio government to issue building permits inside the John Hay Special Economic Zone (Condition No. 1), which BCDA also questioned in court.

At the city’s Malcolm Square stands the bust of Supreme Court Associate Justice George Malcolm, to whom historians credit the drafting of the original 1909 Baguio Charter.

Recognizing Ibaloys

Magalong on May 12 said “no charter can be perfect,” and suggested that crafting its implementing rules and regulations (IRR) would cure any perceived defects. Discussions about the IRR were started on May 19.

“It would have been nice if the new charter recognized the Ibaloys and their ancestral lands,” said newly elected councilor Jose Molintas, an Ibaloy human rights lawyer. Ibaloys were recognized in Section 9 of the 1909 charter which formed a five-member advisory council “who shall be Igorots,” and who could be consulted by the mayor.

Also in 1909, Camp John Hay was the subject of the landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court which recognized the “native title” to lands occupied by indigenous Filipinos. Now called the Native Title Doctrine, it is the foundation for the country’s Indigenous Peoples’ Rights Act (Ipra, Republic Act No. 8371).

The new charter identifies Ipra as the operating law when it comes to Baguio ancestral lands. However, Ipra exempts the Baguio townsite from its coverage, except for Ibaloy lands recognized in the early 1900s.

RELATED STORIES

Baguio councilors seek Duterte veto of new city charter

Senate panel OKs bill seeking to revise Baguio City’s Charter