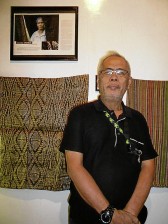

BAGOBO Datu Miguelito Bangkas poses beside a picture of Apo Salinta Monon, the last Bagobo weaver, who died at age 91 in late 2008. GERMELINA LACORTE

DAVAO CITY—As Davao City prepares to celebrate its 75th Charter Day on March 16, Bagobo tribal leader Datu Miguelito Bangkas posed a question: “Where have its earliest people gone?”

He hazarded an answer. “They’re still around,” he said. “But just like their culture, they’ve also been marginalized as a people.”

Bangkas was referring to his people, the Bagobo, the earliest known indigenous tribe in this part of Davao, whose community has been eased away from the center of power throughout history with the coming of migrants from the Visayas and Luzon.

“Just like our culture, you can hardly see the original Bagobos,” he said. He recalled how his mother once threw away her beads and indigenous dresses when she converted into Protestantism and was told that wearing them was a “sin.”

“We were told that even playing the gong was tantamount to calling the devil,” Bangkas said.

As this year’s Araw ng Dabaw celebration kicks off this week, Bangkas mounted the exhibit, “Bagobo Memories,” a showcase of photographs, artifacts and crafts exploring the Bagobo tribal art designs that in their own way tell the indigenous people’s stories throughout history.

Orly Escarilla, the director of the Museo Dabawenyo, said the exhibit aimed to create awareness on the life in the tribe, its traditions and practices, among the people of Davao and visitors.

St. Louis Exposition

From the photographs of the 27 Bagobos brought to St. Louis, Missouri, in 1904 to be displayed at the St. Louis Exposition to the handwoven abaca fabric by Apo Salinta Monon, the country’s living treasure who died in 2008, the exhibit showed the Bagobo journey through time.

Through the photographs, Bangkas talked about the Bagobos who first arrived in the United States. “There were supposed to be 28 of them,” he said. “But one of them did not make it through the two-month sea journey and died along the way.”

“Some of them were held against their will. The boat that was supposed to carry them to the United States stayed in Darong in Santa Cruz town for a long time and some of them already wanted to go home,” Escarilla said.

The St. Louis Exposition was not a moment of pride but of humiliation not only for the Bagobos but also for other ethnic groups. It sought to convince the American public that Filipinos were “uncivilized,” hence, the need to be put under the tutelage of the US government. It justified the US conquest of the Philippines.

The St. Louis photograph showed 27 Bagobos carrying a nipa hut, parts of which were transported all the way from Davao to Missouri for the exhibit. Datu Bolong donned a waist-long hair, a symbol of bravery and courage.

Bangkas said he only learned about what happened when a friend brought him to watch a play at the University of the Philippines in Diliman, Quezon City, in 1993.

Bagobo mayor

“Araw ng Dabaw is a good celebration,” Bangkas said. “As a matter of fact, it was conceived by a mayor who was a Bagobo,” he said, recalling fondly Elias Baguio Lopez, the grandson of Datu Baguio who once ruled over the wide tracts of land that people identify now as the Baguio district.

Lopez, the 16th and 19th mayor of the chartered Davao City, strove to unite the Moro and indigenous tribes with the settlers from Luzon and Visayas.

Bangkas poignantly remembered the day when he accompanied anthropologist Cherry Quizon on a trip to look for the last Bagobo weaver and tracked her down in Bitaug, Bansalan, Davao del Sur. Apo Salinta Monon, later declared by the National Commission for Culture and the Arts (NCCA) as one of the country’s living treasures, had once stopped weaving the Bagobo’s abaca fabric called “inabal” because it was selling very cheap in the market.

Among the rare collections on display at the exhibit was one of Apo Salinta’s woven abaca cloth featuring the rare “binuwaya” (crocodile) design. Bangkas said it could be the last binuwaya design made by a Bagobo as no one among the new generation of Bagobo women weavers have mastered the intricate technique mastered by Apo Salinta.

Religious conquest

“What changed the Bagobo?” Bangkas asked. “It was the coming in of the new religion, the potent force for conquest,” he said.

“When Christianity arrived, they told us all that we practiced were all works of the devil,” he said.

Almost a hundred years later, he said, during the celebration of the Philippine Centennial, he discovered cartloads of old Bagobo artifacts, the kind that could no longer be found in Mindanao nowadays, displayed and occupied the whole wall of the Smithsonian Museum.

On the walls of the Davao museum, he pointed at the photograph of “ka bie,” a fully beaded Bagobo backpack adorned with brass bells. “That could no longer be found here,” Bangkas said. “I saw that at the Smithsonian.”