Threats vs the unvaxxed: The failure to see realities

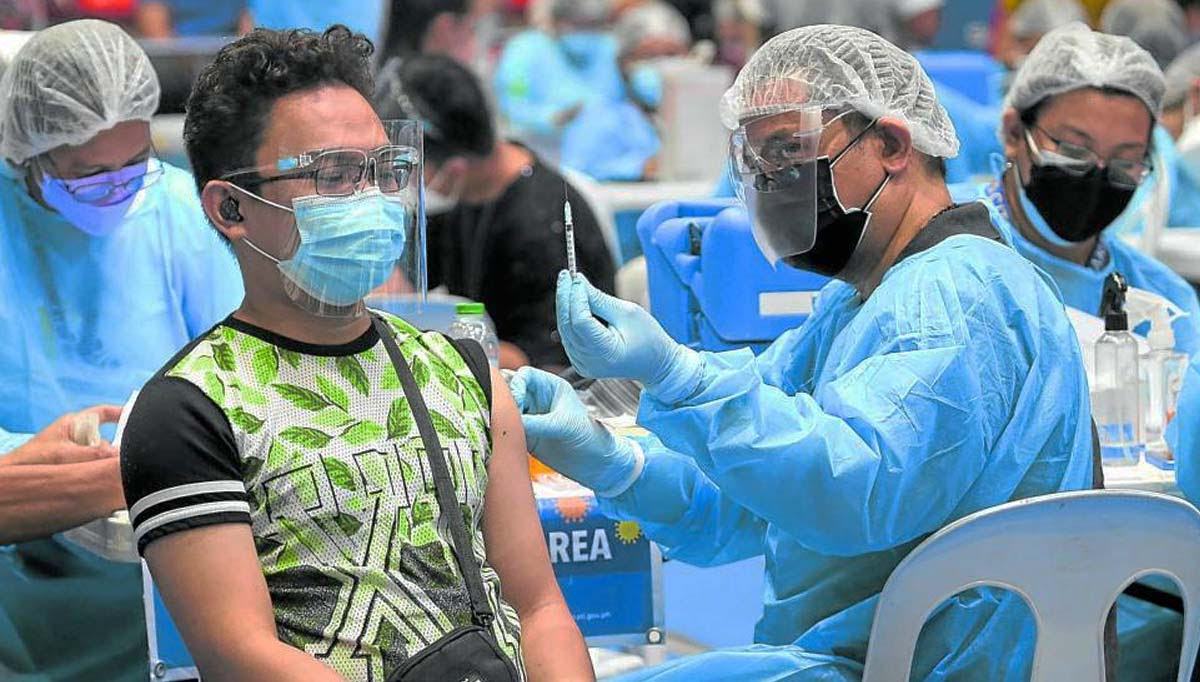

FILE PHOTO: Postgraduate or undergraduate interns, clinical clerks and fourth year medicine and nursing students have been cleared to serve as screeners, vaccinators and vaccination monitors as part of their internship. —LYN RILLON

MANILA, Philippines—“Bahala kayo (You’re on your own).”

As COVID-19 cases rise in the Philippines, President Rodrigo Duterte addressed himself to people who are not yet vaccinated, saying that he will not help them even if they die.

“Those who did not get vaccinated, if you get sick, the risk of dying is there. So it’s up to you. If you ask me for help, I will not help you because you didn’t get vaccinated,” he said on Jan. 4.

“If you were vaccinated. We shouldn’t be worrying about it. If you die, then, you’re on your own,” he said, pointing to rising hospital admissions and contaminations.

But when Duterte issued this threat–his latest since May 2021–he might have forgotten two things. First is that vaccination was not mandatory. Second are the valid reasons people fail to get vaccinated.

‘Not easy’

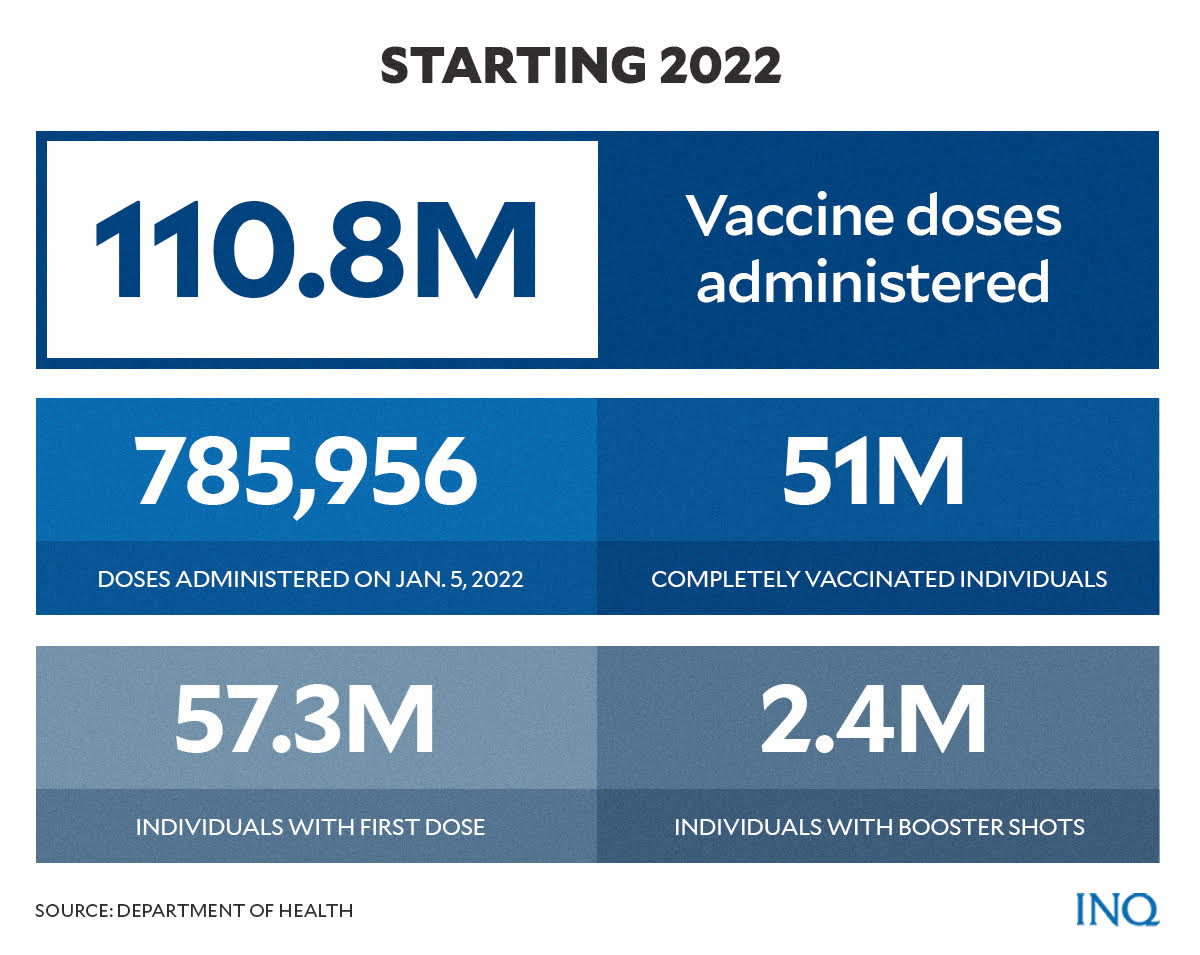

The Department of Health (DOH) said on Jan. 5 that the Philippines had already given out 110,875,575 COVID vaccine doses–785,956 were administered on that day.

It said 51,085,070 individuals are already fully vaccinated, 57,328,625 already received the initial dose and 2,461,880 already received booster shots.

Among those who have not been vaccinated previously was Castlene Oda, a 23-year-old single mother, who decided to have her first dose but not because of Duterte’s threats.

She told INQUIRER.net that she wanted to get vaccinated in 2021 but wasn’t able to because of several reasons, mainly lack of time and money.

“I am a single mother and I had a lot of considerations since I know that vaccines have side effects. Who will take care of my child? How will I get to work?” Oda said.

This, she said, was the reason she and her father decided to get vaccinated “one at a time” so that either of them could still work and take care of her child in case side effects sidelined them.

The Philippine Statistics Authority said that in Isabela province alone, a family of five needed to earn P10,579 monthly to meet food and non-food needs. This meant an income of at least P352 per day.

Without P352, a family of five would hardly survive the day. “While we really want to get vaccinated immediately, there are things we really need to consider,” she said.

Since Oda wasn’t able to get vaccinated when local health officials went to her barangay, she needed to spend P100 for transport to get to the rural health unit and another P100 to return home.

Endless threats

Dr. Regi Pamugas, representative of the group Health Action for Human Rights, said Duterte’s threats will not convince people to get themselves vaccinated against COVID.

READ: Reckless statements behind jab panic: If that ‘somebody’ is Duterte

“We’re almost two years into the COVID-19 crisis and he did not yet learn,” he told INQUIRER.net, saying Duterte should do more to convince people to take the vaccine.

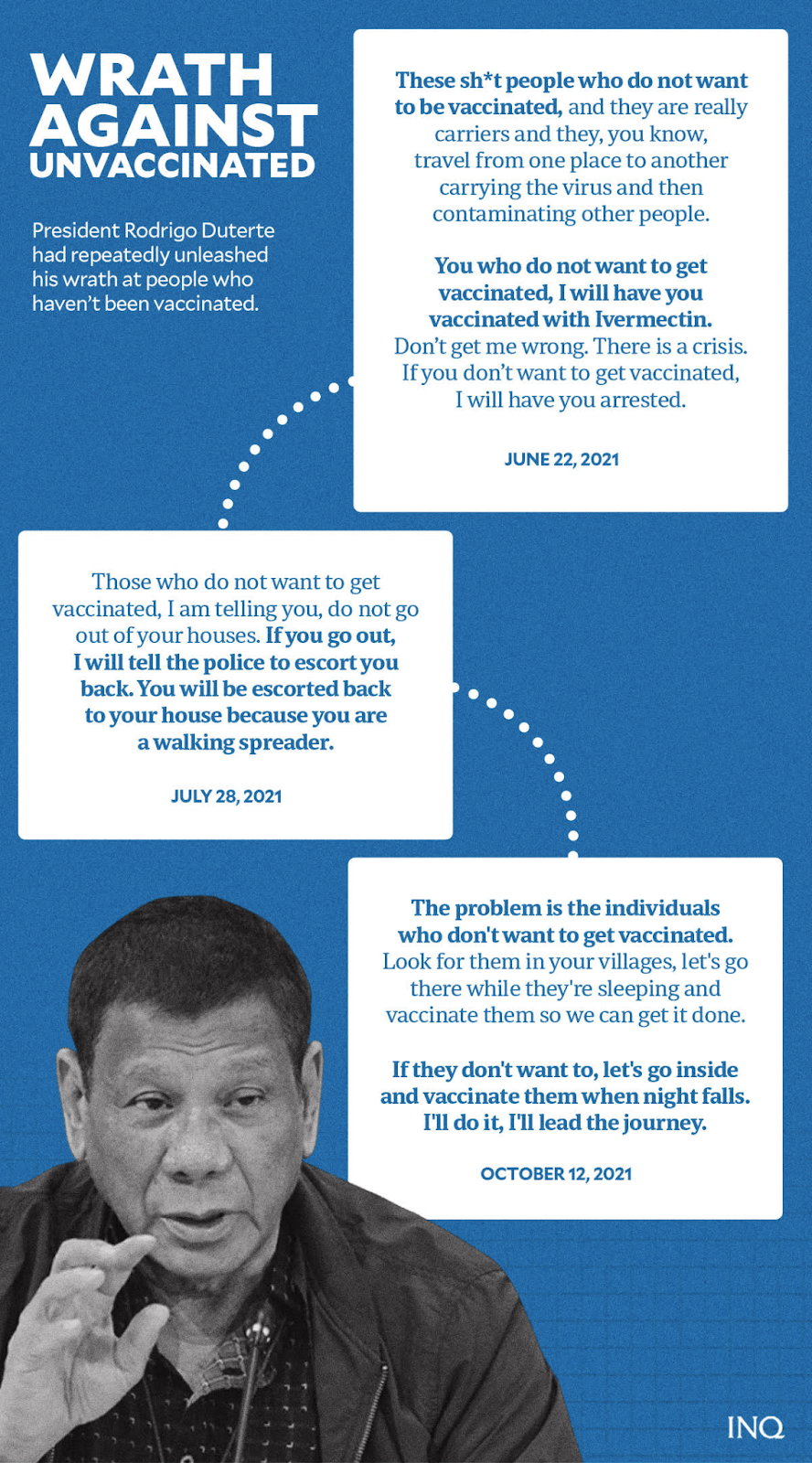

The President’s “no help, even if you die” quip was the latest in the string of threats he made against people who have not been vaccinated yet. A review of his previous statements showed a consistent strategy to threaten people:

- June 22, 2021

When the Philippines administered 8.4 million vaccine doses, Duterte threatened people who refuse vaccination with arrest and injection of ivermectin, a veterinary medicine.

“These sh*t people who do not want to be vaccinated, and they are really carriers and they, you know, travel from one place to another, carrying the virus, and then contaminating other people,” he said.

“You who do not want to get vaccinated, I will have you vaccinated with Ivermectin. Don’t get me wrong. There is a crisis. If you don’t want to get vaccinated, I will have you arrested.”

- July 28, 2021

As he addressed Filipinos, Duterte ordered police and barangay officials to “escort” unvaccinated people back to their houses if they were found outside.

“Those who do not want to get vaccinated, I am telling you, do not go out of your houses. If you go out, I will tell the police to escort you back. You will be escorted back to your house because you are a walking spreader,” he said.

- Oct. 12, 2021

While Delta, a more transmissible variant of SARS Cov2, brought deaths to the Philippines, Duterte said he had an idea to address vaccine hesitancy.

“The problem is the individuals who don’t want to get vaccinated. Look for them in your villages, let’s go there while they’re sleeping and vaccinate them so we can get it done,” Duterte said.

“If they don’t want to, let’s go inside and vaccinate them when night falls. I’ll do it, I’ll lead the journey,” he said while missing the fact that there’s no law mandating vaccination.

On Dec. 22, 2021, Duterte said the government’s insistence on vaccinations, despite hesitancy, was the reason for a downtrend in infections late last year.

READ: ‘It was a good move to insist vaccination’: Duterte raises possibility of mandatory jabs

Sinking the poor

Last year, while the government said the rollout of vaccines slowed down because of “throughput,” proposals to ramp vaccination up ran into criticisms as these were deemed anti-poor.

READ: PH injection rates fail to catch up with vaccine supply

The Department of Interior and Local Government (DILG) said on Nov. 6 that the government was proposing to exclude the unvaccinated poor from the cash assistance program.

It said many of more than 4 million Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program (4Ps) beneficiaries were not yet vaccinated while some even declined vaccination.

As a remedy, it proposed to “disincentivize” them for being unvaccinated as the 4Ps program was “conditional,” according to the DILG in a dzBB report.

READ: No vaxx, no cash for the poor: Missing the numbers

Like Duterte, however, the DILG failed to recognize key reasons why people, especially the poor, remained unvaccinated.

The Social Weather Stations (SWS) said on Aug. 17, 2021 that results of its survey on vaccine hesitancy said while 68 percent of Filipinos found easy access to vaccination sites, 29 percent had no access at all, while 3 percent had difficulty in access.

It found out that “easy access” was highest in Metro Manila (83 percent), Mindanao (71 percent), Visayas (67 percent) and Balance Luzon (62 percent).

The SWS said “no access” was highest in Balance Luzon (35 percent), Visayas (29 percent), Mindanao (26 percent) and Metro Manila (16 percent).

There were also complaints about “slow” vaccination pace in barangays–Visayas (58 percent), Balance Luzon (53 percent), Mindanao (48 percent) and Metro Manila (39 percent).

SWS said complaints about the slow vaccination pace in the Philippines was highest in Metro Manila (57 percent), Balance Luzon (55 percent), Visayas (51 percent) and Mindanao (33 percent).

The DOH said on Jan. 5 that the Philippines has already vaccinated 15,478,105 from the indigent population (A5)–6,946,027 (complete), 8,434,194 (initial) and 97,984 (booster).

In the A1 group–health care workers and expanded population–6,233,554 individuals already received vaccines: 2,812,192 (complete), 2,845,598 (initial) and 575,764 (booster).

There were 11,266,943 vaccinated individuals from the A2 group–the elderly population: 5,693,102 (complete), 4,930,636 (initial) and 643,205 (booster).

In the A3 group–persons with existing illnesses and expanded population–there are 17,015,825 vaccinated individuals: 8,701,936 (complete), 7,683,158 (initial) and 630,731 (booster).

There are 35,001,386 vaccinated individuals in the A4 group–the workers in essential services: 16,204,732 (complete), 18,391,489 (initial) and 405,165 (booster).

There are 25,879,662 vaccinated individuals among the rest of the population–10,727,081 (complete), 15,043,550 (initial) and 109,031 (booster).

The real need

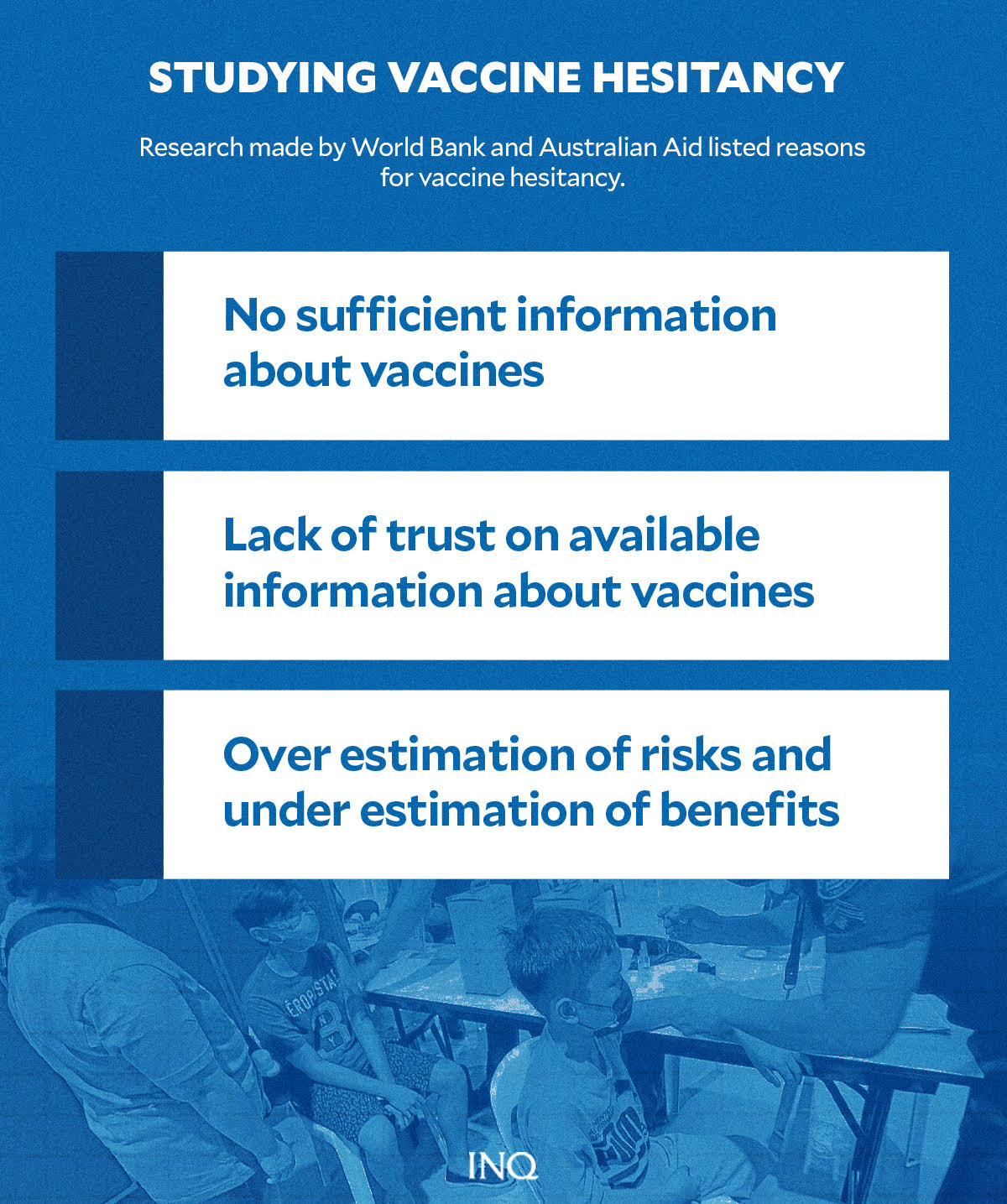

The World Bank and Australian Aid said in a September 2021 research study that with almost half of Filipinos “not willing or not certain” to receive vaccines, hesitancy is high in the Philippines.

While it was easy to conclude that hesitancy meant simply declining vaccination, the study said problems with messaging and information were among the main reasons for hesitancy.

It said lack of information about vaccines, misinformation about their efficacy and side effects, mistrust and a misreading of vaccine benefits are part of the “potential reasons”.

There are three potential reasons for vaccine hesitancy, the World Bank and Australian Aid said:

- Individuals may not have access to sufficient information about vaccines.

- Even when information is widely available, individuals may not fully trust the information or its source.

- Even when information is available and trusted, individuals may incorrectly assess the relative benefits of vaccines by overestimating risks and underestimating benefits.

To address hesitancy, these experiments were held:

- Reverse endorsement: Mistrust was tackled by asking the respondents to think of someone who could endorse and exert positive influence on the vaccination campaign.

- Simplified information: Respondents were reminded that regardless of vaccine brands, vaccines are effective in providing protection for individuals, especially frontline workers, from the worst symptoms of COVID-19.

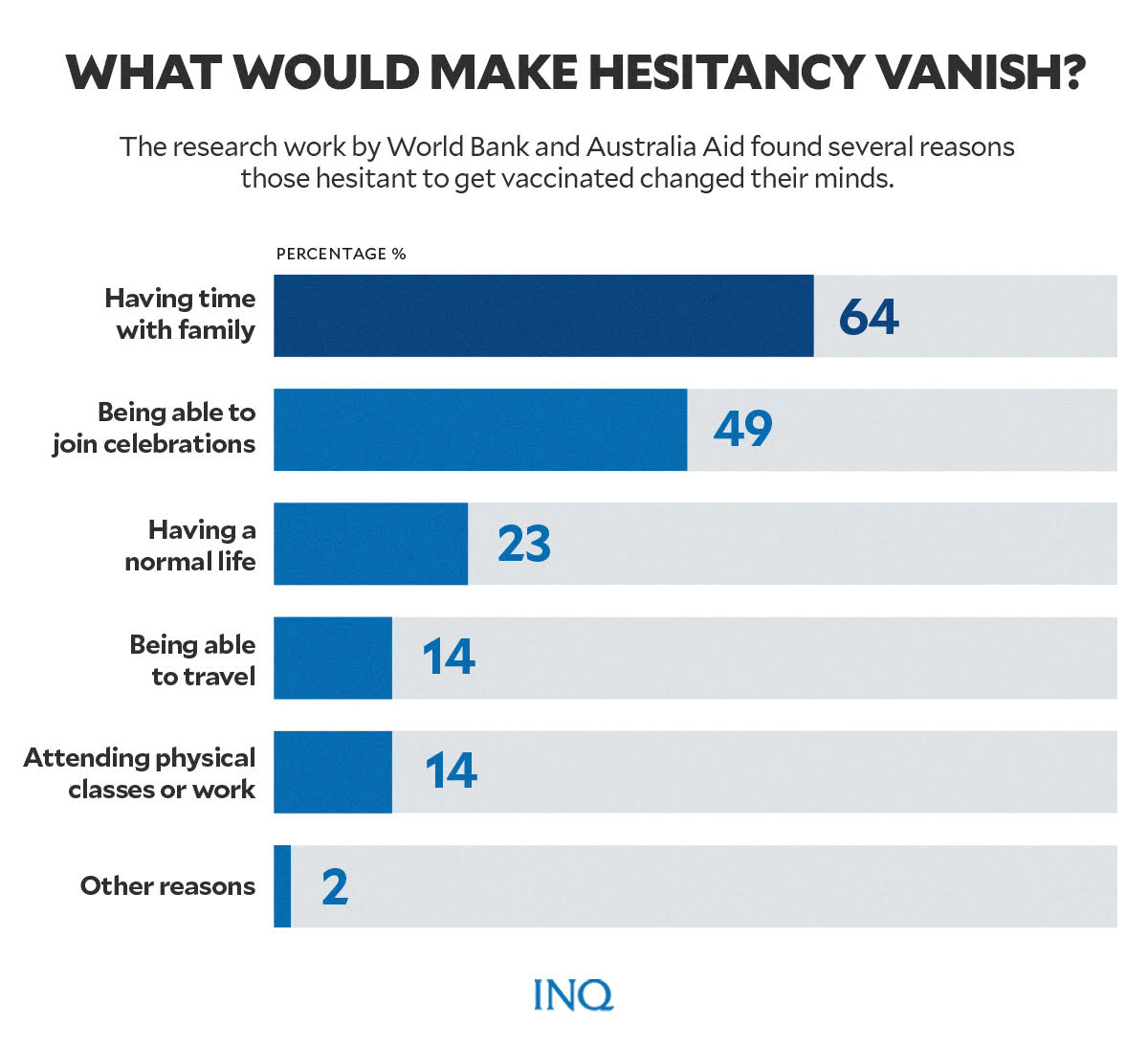

- Personal benefit: The benefits of vaccination to the individual were highlighted by prompting respondents to think about activities that they look forward to when life returns to normal.

- Social benefit: Respondents were reminded of the social benefits of vaccination by asking them to identify who they want to protect and who they think about when making the decision to be vaccinated.

The research found that all reasons had a significant effect in lessening vaccine hesitancy, but the strongest was when people were reminded of the vaccine’s personal and social benefits.

The activities that respondents looked forward to the most were time with family (64 percent), celebrations (49 percent), normal life (23 percent), travel (14 percent), in-person school or work (14 percent) and others (2 percent).

People that respondents said they want to protect were children (54 percent), parents and grandparents (39 percent), extended family (25 percent), friends (11 percent), whole family (11 percent), neighbors (8 percent), spouse (8 percent), self (5 percent) and others (3 percent).

“Regardless of the source of vaccine hesitancy, interventions to encourage vaccination by simplifying messages and emphasizing benefits can be effective,” the research work said.

RELATED STORY: EXPLAINER: The Philippines’ COVID-19 alert level system

TSB

For more news about the novel coronavirus click here.

What you need to know about Coronavirus.

For more information on COVID-19, call the DOH Hotline: (02) 86517800 local 1149/1150.

The Inquirer Foundation supports our healthcare frontliners and is still accepting cash donations to be deposited at Banco de Oro (BDO) current account #007960018860 or donate through PayMaya using this link.