MANILA, Philippines—Did you know that malaria, a life-threatening disease caused by parasites that are transmitted to humans through the bite of an infected mosquito, was once one of the most leading causes of death in the Philippines?

According to Proclamation No. 1168 signed by then-President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo in 2006—which declares November as Malaria Awareness Month—malaria was then the 8th leading cause of death in the country mostly affecting pregnant women, children, and indigenous population groups.

“Malaria remains endemic in 65 of the 79 provinces affecting 12.5 million Filipinos, with pockets of high endemicity along municipal/provincial borders, in far-flung remote areas and barangays populated by indigenous cultural groups and areas with socio-political conflicts,” the proclamation read.

“Malaria, with morbidity rate of 55 per 100,000 population and mortality rate of 0.17 per 100,000 population, has to be reduced and controlled by effective malaria prevention and treatment measures, such as increase in the use of insecticide-treated mosquito nets and early diagnosis and prompt treatment in malaria risk areas,” it added.

However, the number of malaria cases in the country has been going down since then.

In observance of Malaria Awareness Month, here are available data and details about the disease, which has once plagued the country.

What is malaria?

According to the Department of Health (DOH), malaria is a parasitic infection caused by Plasmodium parasites transmitted by the bite of an infected Anopheles mosquito.

There are five kinds of malaria parasites that can infect humans: Plasmodium falciparum, P. vivax, P. ovale, P. malariae, and P. knowlesi — which the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) said “naturally infects macaques in Southeast Asia, also infects humans, causing malaria that is transmitted from animal to human.”

Two of these species – P. falciparum and P. vivax – were identified by the World Health Organization (WHO) as the most dangerous.

“Untreated, P. falciparum malaria may progress to severe illness and possibly, death,” said the DOH.

Malaria vs. dengue?

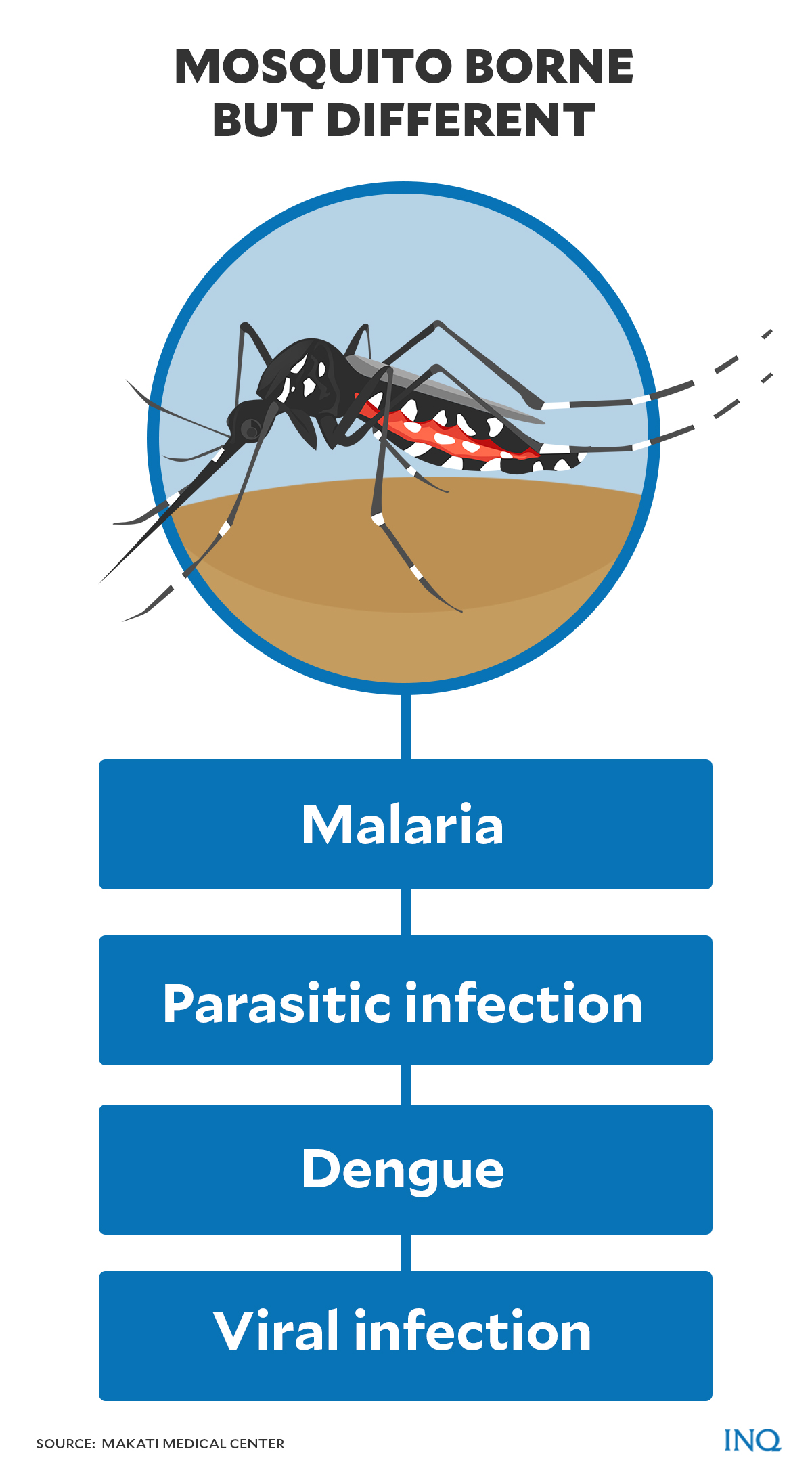

Malaria and dengue are often “lumped together” since they are both caused by a mosquito bite.

Both diseases are also common in tropical and sub-tropical countries like the Philippines.

READ: Dengue fever: Upstaged but not outmatched by COVID-19

However, according to Makati Medical Center (MMC), a key difference between the two is that malaria is a parasitic infection — an infectious disease caused by a parasite — while dengue is a viral infection.

“Malaria is transmitted only by female Anopheles mosquitoes because they depend on blood meals for egg production,” MMC explained on its website.

“Once an infected female Anopheles mosquito initiates a blood meal on a non-infected human, it injects the Plasmodium parasite through its salivary glands, beginning its life cycle and maturing in the human body,” it added.

The parasite, MMC said, initially replicates in the liver.

“Once its life cycle reaches the blood stage, where the parasite begins to affect the red blood cells, clinical manifestations take effect in the human host.”

Malaria burden

In a statement last April 26, the DOH said the country’s malaria incidence declined by 87 percent from 48,569 in 2003 to 6, 210 cases in 2020.

The number of deaths caused by malaria has also declined by 98 percent, from 162 deaths in 2003 to only three deaths in 2020.

“Along with this is the shrinking geographic extent of malaria, with 60 provinces officially declared by the DOH as malaria-free, and an additional 19 provinces having reached malaria elimination phase with zero local transmission, waiting to be assessed and declared malaria-free provinces,” the DOH said.

“At the end of 2020, only 126 barangays from 2 provinces in the country have recorded local malaria transmission,” it added.

This was despite WHO’s warning on the COVID-19 pandemic’s “devastating” impact on the global fight against malaria in 2020.

READ: COVID-19 has ‘devastating’ impact on fight against HIV, TB, malaria–Global Fund

The WHO said last year that malaria-related deaths could possibly double during the COVID-19 pandemic.

READ: WHO warns malaria deaths could double during coronavirus pandemic

“The COVID-19 pandemic may have impacted the delivery of services under our malaria elimination program, but this will not deter us from our vision of a malaria-free country,” Health Secretary Francisco Duque III said.

“We, at the Department of Health, reaffirm our commitment to eradicate malaria,” he added.

Based on WHO’s World Malaria Report published last year, the Philippines’ suspected malaria cases slightly increased from 314,788 in 2010 to 343,174 in 2019 — which is lower compared to 443,997 in 2018.

The number of presumed and confirmed cases went down from 19,648 in 2010 to 5,778 in 2020.

In 2010, there were 301,031 microscopies examined in the country, 18,560 of which turned out to be positive. The figures decreased in 2019 with 170,887 microscopies examined and 1,370 positive cases.

The number of imported cases, however, increased in the country. WHO data showed that there were no imported cases of malaria detected in the Philippines between 2010 to 2013.

In 2014, there were 68 imported cases recorded and it has since then increased to 95 in 2019.

The DOH is aiming for a malaria-free Philippines by 2030.

Signs and symptoms

Some of the symptoms of malaria that might manifest at the beginning of the disease, according to the US CDC, are fever, sweats, chills, headaches, malaise, muscles aches, nausea, diarrhea, and vomiting.

Malaria can also lead to anemia and jaundice, which causes the color of the skin and eyes to turn yellow, due to the loss of red blood cells.

The incubation period takes anywhere from seven to 30 days.

“If not promptly treated, the infection can become severe and may cause kidney failure, seizures, mental confusion, coma, and death,” the US CDC added.

Treatment and breakthrough

While it can be fatal, malaria is preventable and curable.

According to MMC, diagnostic examinations like blood tests and other tests for possible complications are available in the country for suspected malaria cases.

Prescription drugs, which aim to kill the parasite, are also given as treatment for malaria. A vaccine called RTS, S — the only approved vaccine against malaria — can also help reduce severe-to-life-threatening malaria, the MMC said.

Last month, the WHO has endorsed the widespread use of the RTS, S vaccine by British drugmaker GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) among children in sub-Saharan Africa and in other regions with moderate to high transmission of P. falciparum malaria.

“This is a historic moment. The long-awaited malaria vaccine for children is a breakthrough for science, child health, and malaria control,” said WHO Director-General Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus.

“Using this vaccine on top of existing tools to prevent malaria could save tens of thousands of young lives each year,” he added.

READ: WHO endorses first-ever vaccine against malaria

Results of an initial clinical trial for a vaccine developed by French researchers from Inserm and the Université de Paris, which aims to protect pregnant women and unborn children from malaria, was released in February.

Researchers found that the vaccine was able to produce an immune response, with antibody production in 100 percent of vaccinated women after only two injections.

“We were able to show that the vaccine is well-tolerated, at all the tested doses. The side effects observed were mainly pain at the injection site. We also revealed that the quantity of antibodies generated by the vaccine increases after each vaccination and that they persist for several months. It therefore appears that the vaccine has the capacity to trigger a lasting and potentially protective immune response,” said CNRS research director and project leader Benoît Gamain.