MANILA, Philippines—Whether it is to stress a point or to simply amuse, President Rodrigo Duterte’s unpredictable rhetoric has sown confusion about government policy on fighting COVID-19, which marred his fifth year in office.

More often than not, the so-called damage control falls onto the shoulders of his spokesperson and his Cabinet members. Whatever the President says may not be the last word and would need decoding by his alter egos.

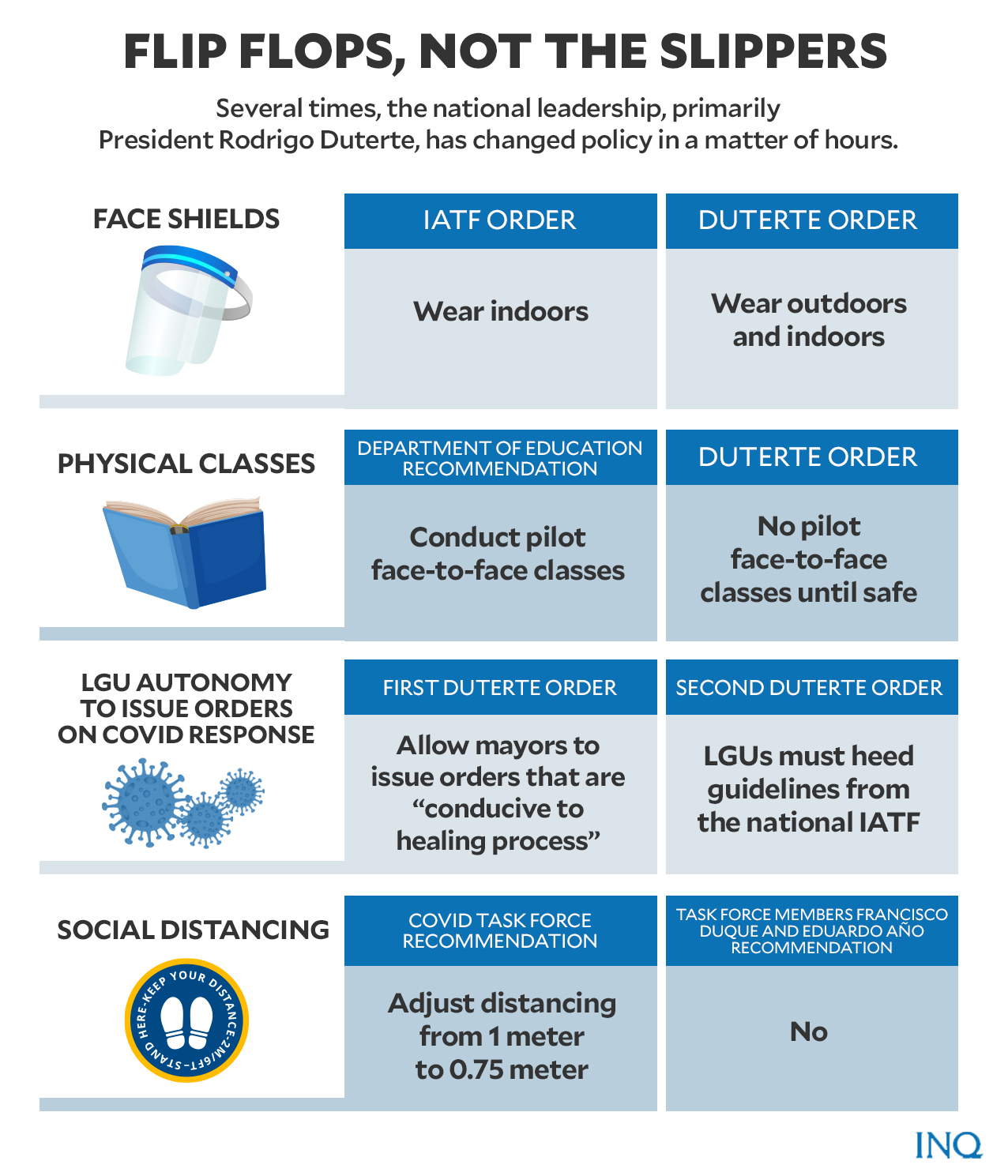

At times, it’s Duterte who counters the decision of his men, whether the Cabinet or Inter-Agency Task Force (IATF) for the Management of Emerging Infectious Diseases, the government’s policy-making body for pandemic response.

For many, this is no longer a surprise. The President is no stranger to making headlines with his controversial remarks since he won and assumed the presidency in 2016.

One very familiar instance was a promise he made during the presidential campaign to assert Philippine sovereignty in the West Philippine Sea by riding a jet ski and planting a Philippine flag there.

The bravado, some experts said, won him votes. Five years later, however, Duterte would be taken to task for doing the opposite of his fiery promise to assert Philippine sovereignty in the West Philippine Sea. Duterte recently admitted it was just a “campaign joke”.

On a range of issues in response to COVID-19 pandemic that is filled with uncertainty, some would say changes in rules simply meant the government was receptive to suggestions.

For some, however, the health crisis’ unpredictability was what required clarity from the government.

In the haze created by rules that change on a regular basis, the cry for clarity is growing: “Ano ba talaga?”

Face shields: To wear or not to wear?

Relief was the reaction of many when Senate President Vicente Sotto III announced on Twitter that face shields are no longer mandatory except inside hospitals, citing a statement from the President himself.

Some lawmakers had been questioning the requirement for face shields since the Philippines appears to be the only country mandating its use. That is why Sotto’s announcement was met with a positive response by the public and his fellow lawmakers.

Duterte’s spokesperson, Harry Roque, even affirmed that the President’s pronouncement can be considered policy, though he also noted that the IATF can still appeal this—which it did.

The IATF recommended that the wearing of face shields still be required in enclosed or indoor spaces like hospitals, schools, workplaces, commercial establishments, public transport and terminals and places of worship.

But Duterte’s final word? The wearing of face shields remains mandatory both indoors and outdoors.

The President, in an attempt to explain his wishy-washy statement, said he never declared with finality that the government would do away with the face shields requirement.

“When I mentioned about the face shield, I was only shooting the breeze with the congressmen, the members of Congress who were there,” he said.

Duterte apologized for the policy changes, recognizing the confusion it created.

Amid criticisms, Malacañang stood its ground that there is nothing wrong with flip-flopping especially if it is warranted by supervening events. As the virus that causes COVID-19, SARS Cov2, mutates into more transmissible variants, Roque justified the sudden policy change as away to adapt and protect the people based on what science says.

Pilot face-to-face classes

In January, the Department of Education (DepEd) somehow got the President to allow the conduct of pilot face-to-face classes in select schools located in areas deemed low-risk for SARS Cov2 transmission.

The dates were even set for the dry run for these limited in-person classes.

But when the new SARS Cov2 variant first detected in the United Kingdom emerged, Duterte recalled his approval of the pilot project.

“I will not allow face-to-face classes for children until we are through with this,” said Duterte.

Come June, the President still opposed the resumption of limited face-to-face classes, this time due to the threat of the COVID-19 Delta variant first detected in India. He also insisted that he would allow schools to reopen only after children get vaccinated against SARS Cov2.

Duterte said he wants “normalcy” for children’s education, but could not gamble with their lives, prompting another apology from Duterte.

Five months since the vaccination drive began, over four million persons have so far been fully vaccinated against SARS Cov2. But children have yet to be included in vaccine priority due to the limited supply of doses.

Physical distance in public transportation

The Duterte administration also ran into some bumps in policies surrounding transportation, one of the most hard-hit sectors at the start of the pandemic.

Aside from the ridiculed motorcycle barrier requirement, another policy that raised eyebrows was the reduction of physical distance between commuters from one meter to 0.75 meter.

The COVID-19 task force approved the reduced physical distancing, so said Transportation Secretary Arthur Tugade then. But it turned out that Health Secretary Francisco Duque III, chairman of the task force, and Interior Secretary Eduardo Año opposed the proposal.

Implemented on Sept. 14 last year, the reduced distance policy was suspended three days later due to concerns by health experts that it might cause more COVID transmissions.

Ultimately, the President stood by the policy that the one-meter distance rule in public transportation remained in effect, siding with his health secretary, doctor, and health worker groups.

’Timeout’ in Mega Manila

Despite the often wishy-washy stand on issues, some instances would make one realize that Duterte reversed some policies after listening, or perhaps feeling pressure, on what others say.

It was in June 2020 when the government began to loosen quarantine restrictions gradually, with Metro Manila and nearby provinces Bulacan, Rizal, Cavite, and Laguna or Mega Manila placed on general community quarantine, the loosest form of lockdown.

But by the end of July of that year, health workers and experts warned that increasing COVID-19 cases were already pushing medical facilities to their limits, appealing for a “timeout” to prevent the health care system’s collapse.

Even with the warning, Duterte and his task force retained GCQ over Metro Manila and nearby provinces Bulacan, Rizal, Cavite, and Laguna or Mega Manila.

The decision was made only to be taken back three days later following heavy pressure from health workers’ groups. Duterte heeded the frontline workers’ plea by imposing stricter restrictions on Mega Manila and placing it on modified enhanced community quarantine (MECQ).

Local government’s power

By this time, the public may no longer be surprised by the President’s sudden changes on policies. Considering that since the day Duterte declared a State of Public Health Emergency due to COVID-19, he had already been issuing confusing statements.

The President had given a go signal for local chief executives to issue orders that will make their localities “more conducive to a healing process” amid the crisis.

“Just go ahead and the mayor will do it for us,” said Duterte.

“So there won’t be much ruckus, no debate, just one, only one line today, mayor first,” he said. “And he can come up with any measure to protect public health, public interest, public order, public safety and whatever is needed to make life more livable in your place,” Duterte said in a speech on March 16, 2020.

Three days later, the President did a 180 and warned mayors against going beyond the national government’s guidelines on quarantine restrictions.

Duterte, who had been Davao City mayor for more than two decades, said it was the national government’s job to “call the shots” while the local government units (LGU) just “comply.”

No particular LGU was mentioned at the time, but the President’s stern warning came on the heels of Pasig City Mayor Vico Sotto’s decision to allow tricycles to operate despite the COVID-19 task force’s policy barring public transport.

Sotto had reasoned that the local government’s vehicles were not enough to ferry health workers to work, hence allowing tricycles to ply their routes will make up for the lack of transportation. Even if the move made sense, Pasig City complied with the ban on tricycles, heeding the national government’s policy.

Shoot quarantine violators?

Upon the imposition of quarantine restrictions, businesses were shuttered, public transportation was barred and people were forced to stay at home. And what could be the most Duterte way to urge the public to follow protocols but warn that they would be ordered shot?

“Don’t test the Filipino. Do not try to test it. You know we are ready for you. Trouble, or gunfight or killing, I will not hesitate to order my soldiers to shoot you. I will not hesitate to order the police to arrest and detain you,” Duterte said in a speech on April 1, 2020.

His warning came after 20 protesters demanding food and assistance were arrested in Quezon City for staging a rally. Duterte’s then spokesperson, Salvador Panelo, downplayed the President’s remarks, saying it was “not a crime” and is based on the principle of “self-preservation.”

After a fierce backlash, Duterte two days later denied giving a shoot-to-kill order against quarantine violators, explaining that law enforces would resort to using violence only if their lives are put in danger.

“I never said in public shoot to kill, period,” Duterte said. “If you think that your life is in danger, your pretty wife would be a widow and marry again and your children will lose a father, if you see your life in danger, death, go ahead, kill,” Duterte said in Filipino.