Today began yesterday

We are taught that the voice of the people is the voice of God, and that is expressed through the ballot. Among our elders, the factors that can censor the people’s choices are known as the “three G’s”: guns, goons, and gold. But as we’ve become a more urbanized and digitally connected nation, guns and goons matter less, nationally speaking, though they are sadly still a reality in many local races. Instead, nationally speaking, it’s data, social media, and the rules that distort the electoral process. What yesterday and today have in common is gold: Politics has always been expensive.

Impresarios as party subs

In 1941 our Senate became what it is today (elected by the entire nation and not by districts) so that it could become a training ground for the presidency. But its proponents also knew the dangers of national office: that celebrity and money could distort elections. So they instituted bloc voting which today’s party list voters would recognize: You voted for a party, and thus all its candidates. This gave parties a fighting chance. But by the 1950s bloc voting was abolished, and soon after, celebrity candidates began to win national positions.

Inquirer columnist Mahar Mangahas of Social Weather Stations has convincingly pointed out that surveys do not create trends in voters’ minds, but fellow columnist Randy David also says impresarios have taken the place of political parties in determining who the candidates are. An impresario is a show-biz term meaning someone who organizes and often finances concerts or plays. In politics, these are the people who promote candidacies and find backers for them. And their chief instruments in putting forward a candidate worth investing in are surveys. Here, ability or track record is secondary to celebrity.

Rewarding party-switching

In his June 20 column, Randy David also pointed out that political parties were destroyed by martial law. Parties never recovered even when democracy was restored. One reason was that we kept Marcos’ barangay system, and it evolved so that it’s supposed to be nonpolitical, theoretically off-limits to parties. This cut off parties at the knees, so to speak, making them political manananggal, all torsos with no legs (the grassroots). Plus, presidents discovered they could simply reschedule barangay elections, making them subservient to every president who extends them in office.

The level where the local meets the national is in the House of Representatives, where congresspeople represent local districts in a national body. Even before martial law, no president ever lost the House; instead, if a president lost reelection, then the House stampeded to join whoever won.

Article continues after this advertisementWith the barangays also freed of accountability because of constant term extensions, this meant the pressure for treating any kind of political affiliation as more than a temporary identity was irresistible. One more thing: We abandoned the two-party system for a multiparty system, but without having what most multiparty systems have, which is runoff elections. This is when many candidates can compete but the top two then square off in another election, so that the winner has a majority.

Article continues after this advertisementInstead, we have a system where our presidents are elected not by majority but by minorities. These have ranged from as low as 23.58 percent (Ramos, 1992) to a high of 42.8 percent (Aquino, 2010): never a majority. This has many implications on the ability of presidents to govern and meet the expectations of a population that still imagines the presidency as being backed by the rule of the majority.

Eye on the prize

Up to 2001, Edsa was the defining narrative of our political society. It nipped in the bud every attempt at term extension for presidents, attempts to amend the Constitution, and booted a president out of office. At the time of Edsa Dos, the Internet Age had just dawned; we were not just the texting capital of the world, but also showed how it could topple presidents. You could argue that Metro Manila’s corner of Edsa and Ortigas in 2001 is where Cairo’s Tahrir Square in 2011 began.

It was also where the restoration of the Marcoses began, though it had already begun with Borgy Manotoc’s easy slide into celebrity life. An entire generation of Filipinos would grow up with three givens: the Marcos’ recovering glitz and glitter through celebrity status; popular disappointment with, and fear of, People Power (Edsa Dos and Edsa Tres); and a relentless, skillful representation of the Marcos mythology on YouTube and social media.

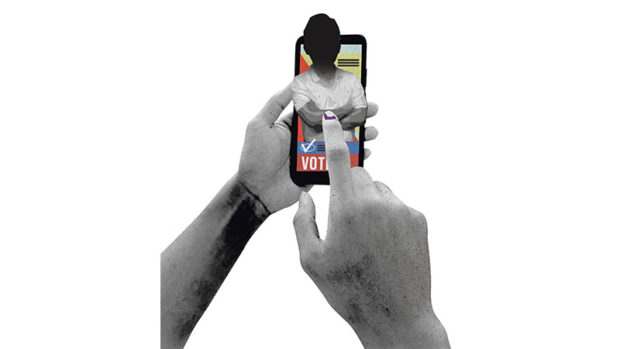

Social media as mediator

It is also the period when the people have become increasingly inclined, locally at least, to view voting as a cash transaction. This means the hold even of entrenched dynasties is much weaker: They have to make deals among themselves to all get elected, and their ability to “deliver” votes through means fair or foul is also weaker. In a practical sense, this means “machinery” as a whole is less reliable up and down the line.

This also means that for national candidates, given mass media’s weakness and limited reach, social media becomes all the more crucial, demanding and indisputable as the means to grab public attention and convert voters from skeptics to believers. But there are limits. The power of negative campaigning may be more powerful than ever before, but there is another trend. Beaten up and bruised by the toxic environment of the past decade, so many Filipinos have retreated to chat apps as zones of relative safety and calm—which may or may not be within the reach of campaigns.

The power of three

Three factors that are less popularly recognized affect the dynamics of our national elections (for the presidency, vice presidency, and the Senate). Briefly stated, they are: first, that the most basic of political positions, the barangay, is unaffected by the May 2022 polls because the barangay elections have been postponed to Dec. 5, 2022. The reason for this is that in general, the first order of business for new administrations, whose barangay chiefs were elected around their midterms, is to move barangay elections to secure the support of barangays in the next presidential election.

Second, no administration has ever lost the House, and that includes administrations that end up losing their bid to succeed themselves. Combined with the barangay election postponements, this means that all barangays and congresspeople have to do is stay officially allied with the incumbent in the Palace until a new one is elected, at which point they instantly change sides—which is welcomed by whoever is the new president.

This also means, since these leaders have their own political networks, that they are seeing who is going to win, whether based on their own intelligence or on the surveys.

Which brings us to the third element: Our leaders are like ourselves. An identifiable trend in our voting behavior is that, according to the surveys, after a winner is declared, more of us remember having voted for the winner than actually did. This also means that immediately after assuming office, most presidents will enjoy a bandwagon effect as people rush to support the new presidency. The public calls it unity, but so do the politicians.