(Editor’s Note: The author is the supreme commander of the Order of the Knights of Rizal and legal counsel of the Philippine Historical Association.)

Who was Jose Rizal’s true love? That’s a question appropriate for Valentine’s Day. It sounds playful, but it’s not.

In recalling the national hero’s affairs of the heart, his popular image as a demigod venerated from afar is rendered more approachable. That Rizal, patriot and martyr, also felt Eros’ gift of ecstasy and pain like everyone else allows us to view him as both heroic and human.

Rizal had many romantic liaisons. Among the women in his life were the flirtatious Segunda Katigbak; the devoted Leonor Rivera; Usui Seiko or O-Sei-San, a descendant of the Japanese samurai class; Gertrude Beckett, who served him hand and foot; the intelligent and rich Nelly Boustead; and Josephine Bracken, whom he considered his wife.

But who among them was his true love? Rizal scholars are divided on the issue though the choice is between Leonor Rivera and Josephine Bracken.

Leonor was a near-cousin and childhood playmate. In April 1880, on his elder brother Paciano’s prodding, Rizal, by then a medical student, went with him to the Rivera house in Intramuros to attend Leonor’s 13th birthday party.

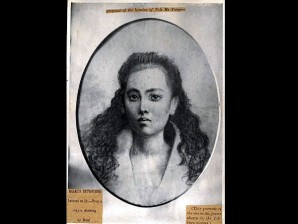

Going by her photograph, Rizal’s pigtailed playmate had blossomed into a slender teenager with an oval face, high forehead, black, smoldering eyes, and thin mouth suppressing a smile.

It was a magical moment: Rizal fell in love. Moreover, he saw in Leonor the inspiration for Maria Clara, the heroine of his first novel, “Noli Me Tangere.”

Epistolary romance

Their paths crossed often after that party. Rizal was a boarder at the Casa Tomasina, which was managed by the Riveras, so Leonor’s presence there at certain times was perfectly valid.

And Leonor and Rizal’s youngest sister Soledad were both boarding students at La Concordia College; Rizal could have frequented the place on the pretext of visiting his sister.

They also wrote to each other, making theirs a long epistolary romance (1880-1890) occasionally marked by words locked in code, the highlight of which was an exchange of troths, with Leonor regarding Rizal as her “unforgettable and dearest lover.”

But none of those letters survived as the two parties, overcome by heartbreak, consigned them to fire.

On May 3, 1882, Rizal left for Europe to continue his medical studies and to obtain reforms for his oppressed country.

He kept his departure from Leonor, who was in Pangasinan that summer. By way of goodbye, he wrote her a short poem expressing the anguish of separation and leaving her his lover’s heart.

Leonor was inconsolable and threatened to dye all her clothes black.

They continued corresponding but they never saw each other again, not even during Rizal’s two trips back to the Philippines.

Filibusterer

Rizal first came home in August 1887. He wanted to visit his beloved but was held back by both his family and the Riveras.

The satirical “Noli” had reached the Philippines, electrifying Filipinos but angering the Spanish authorities who branded Rizal a filibusterer. He and anyone associated with him were closely watched.

He was advised by family, friends and even the governor general to leave the country. When he insisted on staying and marrying Leonor, his brother Paciano intervened, sternly reminding him of his duty to the country.

He sailed back to Europe in February 1888.

The lovers continued writing each other, but Leonor’s mother (“Tia Betang” to Rizal), fearful that marriage to Rizal would bring her daughter undeserved suffering, intercepted their letters by bribing the local postal clerk.

The letters stopped coming for a full year, raising suspicion in the minds of the lovers that the other was being unfaithful.

Meanwhile, Tia Betang ceaselessly importuned Leonor to forget Rizal and marry the Englishman Henry Kipping, a railroad engineer, who could offer her a stable future.

3 conditions

The dutiful daughter gave in, on three conditions: Her mother would stand beside her during the wedding ceremony (it was, after all, really Tia Betang’s wedding), she would never be asked to sing again, and the piano in their house would remain locked as long as she lived.

Then she burned Rizal’s letters. The story is that she sewed some of the ashes into the hem of her wedding dress—and that during the ceremony, Kipping dropped the ring as he was slipping it onto her finger, and it spun several times on the altar floor.

Rizal received Leonor’s announcement of her forthcoming marriage in December 1890, in faraway Madrid. Galicano Apacible, also a cousin, who was with him when he read it, said that “he wept like a child.”

It took almost half a year for Rizal to tell his dear friend and confidant Ferdinand Blumentritt what had happened.

When Rizal returned to the Philippines for the second time in June 1892, there was, of course, no point in seeing Leonor. Besides, within three weeks of arrival he was arrested and banished to Dapitan.

“El Filibusterismo,” the incendiary sequel to the “Noli,” had by then come out; it posited revolution as an alternative to reform efforts that led nowhere.

A year later, in August 1893, Rizal’s mother and his sisters Narcisa, Trinidad and Maria visited him bearing sad news: Leonor had died (of a broken heart, Rizal’s biographer, the Englishman Austin Coates, implied).

As a last request she asked that she be buried in the saya she wore when she and Rizal came to an “understanding,” and that the silver box in which she kept the ashes of Rizal’s burned letters be interred with her.

It is said that Rizal retreated to his room and stayed there for hours, fingering a lock of Leonor’s hair.

‘Point d’appui’

Coates characterized Josephine Bracken as “the leaf in the wind.”

She blew into Dapitan in February 1895 in the company of her adoptive father George Taufer, seeking a cure for his blindness from Rizal, by then a renowned ophthalmologist.

Instead, it was Josephine, an orphan of dubious parentage and checkered upbringing, who found new light in the eye surgeon. Here was her white knight, her salvation.

Rizal, on the other hand, fell for Josephine’s “buxom good looks that had always attracted [him] in Europe.” Or so Leon Ma. Guerrero suggested in his Rizal biography, “The First Filipino,” adding that the hero must have also been captivated by the 18-year-old’s provocative prettiness” with eyes a little bold, sensuous lips and a mass of curly brown hair.”

“Within hours, within minutes, perhaps … [he] was in love, passionately…” Guerrero wrote.

Their meeting also happened at the right time, commented Coates, when Rizal’s “defenses were down” and the loneliness of exile and the pointlessness of living a life with no future in sight were beginning to wear him down.

The two needed each other; each found in the other, in Coates’ words, a “point d’appui,” a fulcrum.

But there were many obstacles to their romance. From the start, Rizal’s family members found it difficult to accept his “golondrina (swallow).”

Short-lived relationship

They regarded her as of little education and therefore clearly out of his intellectual depth; of keeping questionable company (one of her close friends had a friar for a lover and therefore she, Josephine, could be spying for the Church; of lacking the finesse demanded by society’s elite where the Rizals belonged.)

Taufer was also loath to lose Josephine, on whom he had cultivated an unhealthy dependence.

Worse, the lovers could not legitimize their relationship. There was no civil marriage in the Philippines at the time, and the friars refused to marry them unless Rizal retracted his stance on the Catholic Church.

With no alternative and, as Coates reasoned, “there being no impediment in the sight of God, [Rizal] took Josephine as his wife.”

But the relationship lasted less than a year and was made forlorn by a stillborn child. Soon after Rizal’s execution in December 1896, Josephine passed out of the family’s life.

She eventually returned to Hong Kong, married a Filipino, bore a daughter and died of tuberculosis in 1902 at 25.

Playing the field

The question remains: Who was Rizal’s true love?

Guerrero chided Rizal for playing the field in Europe, likening his behavior to “the lordly Victorian male” who expected Leonor “to wait patiently and faithfully at home” while he wrote his novels and cavorted with the Consuelos, O-Sei-Sans, Suzannes and Nellies of the world.

What did he do right after Leonor broke up with him? He cried buckets, then proposed marriage to Nellie Boustead!

That Rizal loved Josephine could be gleaned from his tender regard of his “dear unhappy wife,” his “dulce extranjera … amiga … alegría (sweet stranger, friend, joy).”

But did he truly love her? Or was the union with Josephine, as Coates inferred, merely “a companionship of desolation,” having found in her, and she in him, a buffer against outrageous fortune?

Or perhaps the issue is rendered moot by the popular idea that Rizal’s true love was his country.

Blumentritt believed so. In a letter consoling Rizal after he lost Leonor, the Austrian said: “I know your heart is aching; but you are one of those heroes who overcome the pain of wounds caused by woman because they pursue higher ends. You have a stout heart and a nobler woman looks upon you with love: your native country. The Philippines is like one of those enchanted princesses in the German fairy tales who is kept in captivity by a foul dragon until she is rescued by a valiant knight.”

Just as well

Perhaps at the back of his mind, Rizal knew that he would never marry.

There were two clear episodes in his life—with Leonor and Nelly—when he could have tied the knot had he so desired. And he told Blumentritt as much in a letter dated October 1891, nearly a year after he and Leonor parted ways.

It is believed that men and women with a mission should never marry because their cause, whatever it is, is a demanding and jealous lover. Perhaps it was just as well that Rizal took the solitary road. His legacy to the nation attests to the wisdom of his decision.